Dwayne Michael Carter, Jr., aka Lil Wayne, opened the fifth installment of his Tha Carter series with a tearful message from his mother, claiming pride in her son, followed by acknowledgments that she doesn’t know all that he’d been through. He immediately followed this with the opening track, “Don’t Cry,” featuring a chorus from the late XXXTentacion, a South Florida rapper who had been gunned down in the summer of 2018. Often a rapper willing to bare all on his songs, Wayne’s lyrics hint at something relevant in a majority of music today, including rap: mental illness, depression, and coping through substances.

Since its inception, rap has become a massive cultural and socio-political movement, truly exploding in the 1990s with coast-centric acts like 2Pac and N.W.A. in California and The Notorious B.I.G. and The Wu-Tang Clan in New York. Enter Joan Morgan, the self-proclaimed definitive “hip-hop feminist,” who spent most of the 90’s studying the hip-hop dynamics of gender, violence, and forced marginalization. What she gleaned existed less in the realm of the popularized urban braggadocio, but more within the critical realm. When speaking on the grimly-titled album Ready to Die by The Notorious B.I.G., Morgan said she could “hear brothers talk about spending each day high as hell on malt liquor and Chronic,” declaring that “What passes for ’40 and a blunt’ good times in most of the hip-hop is really alcoholism, substance abuse, and chemical dependency.”

We’ve had nearly twenty years to mull over Morgan’s teachings, and yet rap remains split between bragging about the gangsta lifestyle and the “guilt, regret and depression” that comes along with it. So, what do Morgan’s lessons from the 90’s east coast rap scene have to do with Lil Wayne today, and more importantly, why is mental health so crucial in the hip-hop discourse? To get the best answer possible, let’s dissect the relationship between rap and New Orleans, Lil Wayne’s hometown, and how it serves as a unique microcosm of rap, mental illness, and the American South in the 21st century.

Lil Wayne, or Weezy for short, began his rapping career in 1995 at the age of 12 before reaching the mainstream with his first full-length album, Tha Carter, in 2004. From there, it was a straight shot to the top of the hip-hop world, with the next two entries in Tha Carter series shattering the Billboard charts and winning Best Rap Album in 2009 for Tha Carter III.

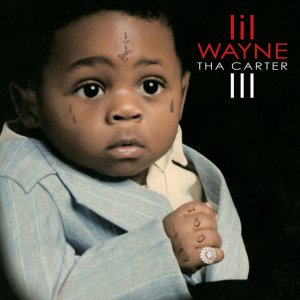

Amid all the success and accolades, though, no one batted an eye at the album cover, featuring a baby Weezy covered in his now-iconic face tattoos. The album cover became so well known that on its tenth anniversary, it was even recreated by a variety of popular figures in the hip-hop scene. But what makes the cover so relevant is the insinuated connection between black youths in America with the hip-hop lifestyle, as if their connection to gangsta life (and its traumatic baggage) has been instilled in them from birth. Behind club hits like “Lollipop” and “Got Money,” which themselves are odes to the gratuitous sex and greed that comes with the culture, we have songs like “Shoot Me Down” featuring lyrics such as these:

“Then I pop another clip in and aim at his vision/’Cause Wayne is his vision, ’cause Wayne is the mission/(I’m aiming at a mirror),”

which shows the inherent nihilism and self-hatred that exists when you find yourself young, black and at the top of your game in America. We even have tracks like “Mrs. Officer,” disguising the hatred for law enforcement as the simple act of seducing an attractive female officer.

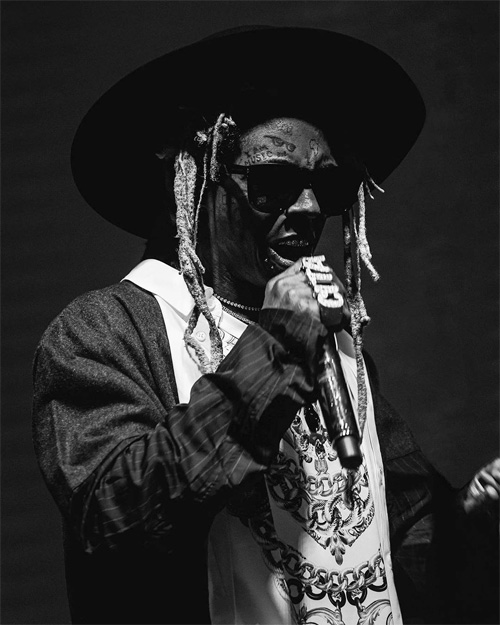

Lil Wayne and his songs represent the rags to riches, “started out hustlin’, ended up ballin’” mentality that many young and impressionable black men admire and may wish to emulate. For black men in the South, especially in New Orleans, Lil Wayne is a hometown hero, the patron saint of the Bling Era and the embodiment of all the desires of black youth.

Ten years was the jump in time between Tha Carter III and Tha Carter V. Within that time, Weezy went from the pinnacle of modern rap, to one of its respected elders, having inspired and collaborated with the next generation of hitmakers. His mark had been made, and through Louisiana heavy hitters like Kevin Gates and NBA Youngboy (whom fans have even dubbed “The New Lil Wayne”), his lyrical legacy and the southern charm of his “sensitive gangsta” music lives on. That leaves us now with dissecting the positive impact of his music, surmised by Tonya Russell as recently as January 2021 for Verywellmind.com. A study by JAMA Pediatrics analyzed 125 rap songs between 1998 and 2018 (the 20-year timeframe including Wayne’s main studio output up to this point). According to their r esearch, “32% of popular songs discussed mental health, and in 2018, that number doubled.” The biggest artists from their research were Jay-Z, Eminem, and Lil Wayne.

esearch, “32% of popular songs discussed mental health, and in 2018, that number doubled.” The biggest artists from their research were Jay-Z, Eminem, and Lil Wayne.

Psychotherapist Alanna Gardner told Verywell Mind, “There’s a positive impact to vulnerability through your art. You’re bound to help someone else add language and feeling to their lived experience.” If Lil Wayne’s music is anything, it’s lived experience. The life, trauma, and emotional turmoil that Weezy raps about in his songs come from a genuine place of historical and social neglect, and represent to legions of young and impressionable fans that they’re not alone. For the youth in a city like New Orleans, where the party never ends and indulgence in vices is intermingled with the historical racism and trauma of the South, the need for voices to speak up on mental health is vital now more than ever. With its de-stigmatization comes change, and from that change comes progress.

This piece was edited by Jiayi Xu as part of Professor Kelley Crawford’s Digital Civic Engagement course at Tulane University.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

[…] Source link admin Send an email 1 min ago0 0 4 minutes read Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Tumblr Pinterest Reddit VKontakte Odnoklassniki Pocket Share Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Tumblr Pinterest Reddit VKontakte Odnoklassniki Pocket Share via Email Print […]