A female portrait from 1840s. (Photo from: Nola Library Archives)

A day in the life of a woman in 1841 New Orleans is what you would expect: she was confined to the home and expected to spend her days doing household chores and raising children while her husband worked outside the home. Surprisingly, Louisiana civil law afforded women marital and property rights that were unprecedented at the time. In contrast, women in other metropolitan cities, like New York, had none of these rights and were expected to remain financially dependent upon their fathers or husbands. The legal status of married women in 1841 presents the false image that there was some semblance of gender equality in New Orleans during that time period, but this notion is false. Women were still confined to the roles of wife and mother and the societal norms that those roles required. The granting of rights to women through Louisiana civil law reform did not make any actual progress for women or gender equality.

Louisiana civil law, unlike common law, was an important piece of legislation for women during this period. A woman was allowed “to retain her legal identity, her personal property and her rights to monetary rewards from her labors within her family,” in addition to owning “half the property accumulated during marriage” and inheriting “her half of the property at the dissolution of the marriage.” In other words, women had some power regarding property ownership and maintenance. These rights did not come without some caveats: “Although Louisiana’s Civil Code enabled a married woman to own property, she could not sell or mortgage whatever property she legally possessed without written authorization from her husband.” These restrictions illustrate the continuous subordination of women under men and negate any argument that Louisiana civil law was striving for gender equality.

Marriage was a social requirement for women to maintain their status or move up through the ranks. Marriage kept women in an inferior position as “fingers were kept busy, while gossip and interchange of bread and cake recipes entertained the housewives who had never heard of cooking schools and domestic science.” Having “meaning and status in society meant to marry and have children- all things domestic.” Society at that time was reliant upon marriage unions for power, money, and status gained through the combining of two families. Young girls were married off by their fathers, and “old maids were rare. Every girl, so to say, married. The few exceptions served to emphasize the rarity of an unmated female.” If a woman did not marry, she was confined to living with her parents, under the control of her father, for the rest of her life. This gives us some idea as to why women were reluctant to utilize their rights under civil law, as many women “upheld the status quo because they could find an honorable identity within the white, male-dominated social structure of the period.”

The domesticity and restriction of women in 1841 New Orleans were partly due to men’s own insecurity. It was the social norm for the husband to be the man of the house and work each day to provide for his wife and children. This explains why “any women working outside the domestic sphere posed a threat to men’s self-image and their potential to make an income.” The widely held “belief that women, as the ‘angels of the house,’ were more moral and nurturing than men” contributed to this vast social divide, as housewives were expected to act as “a buffer against the harsh public world in which their husbands lived.” Even though viewing women as “angels of the house” may appear as a compliment, it only pushed them further into subordination because acting in any other manner could have resulted in harsh consequences like domestic abuse.

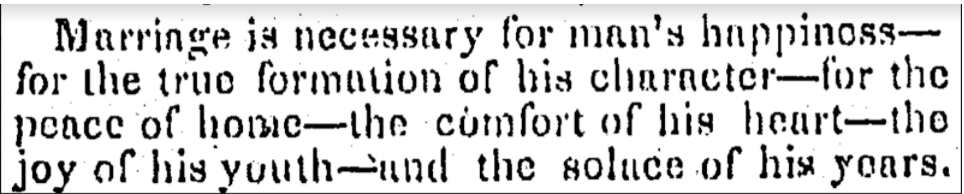

Perpetuating the subordination, a June 11, 1841 issue of the Times Picayune published the following quote:

Publishing such sentiments reinforces the presence of a sexist and misogynistic society. The domesticated role women were expected to play in society was ingrained in them since they were young girls. Recounting her life experiences in New Orleans during the early 1800s, author Eliza Ripley stated: “Is it any surprise that the miscellaneous education we girls of seventy years ago in New Orleans had access to, culminated by fitting us for housewives and mothers, instead of writers and platform speakers, doctors and lawyers — suffragettes?” Young girls were taught to cook simple meals, sew, take care of a baby, and other domestic tasks in school, while young boys learned to read, do math, and comprehend scientific concepts. These ideas were also present in “late eighteenth and early nineteenth century secular and religious guidebooks in America,” as they “generally assigned women a dependent and subordinate status within a narrowly defined female world of home and family.” Publishing literature that so explicitly states the inferiority of women in relation to men only contributes to the patriarchal domination within their society.

Divorce was taboo and rarely occurred, most likely due to the legislation claiming a wife to half of everything her husband owned. In this sense, women had control over their marriages and husbands. It was very clear that “the core of women’s lives in this period was home and family,” and for that reason, “it is not surprising they did not use the law to seek autonomy.” Women, unfortunately, rarely exercised their rights against their husbands or fathers, most likely out of fear of going against the grain.

Life as a woman in 1841 New Orleans was complex and nuanced, as the sexist nature of their society often contradicted their access to legal property rights. Women were relegated to domestic roles within the home; cooking, cleaning, and childbearing dominated their experiences. Nearly every aspect of society contributed to the restriction of women’s education, abilities, and opportunities. Although they had unprecedented legal rights at the time, women rarely exercised those rights because they were deeply committed to their domesticated role of wife and mother.

This piece is part of the “Archive Diving for Future Clarity” series for the Alternative Journalism class taught by Kelley Crawford at Tulane University.

This piece was edited by Anna Blavatnik as part of Professor Kelley Crawford’s Digital Civic Engagement course at Tulane University.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.