“Just so you know, we’re on the good side with y’all. We do not want this war, this violence. And we’re ashamed the President of the United States is from Texas.”

– Natalie Maines of the Dixie Chicks, circa 2003

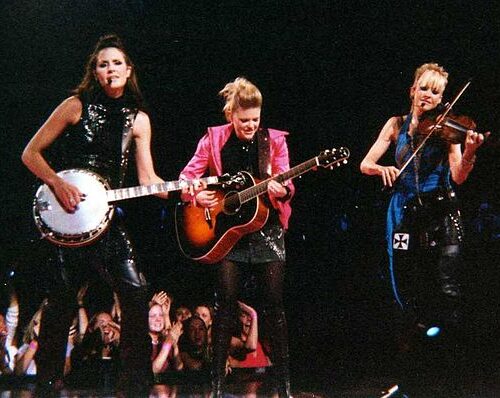

The Dixie Chicks performing at Madison Square Garden in 2003. Source: User Wasted Time R via Wikipedia Commons

In 2003, the frontwoman of the Dixie Chicks, Natalie Maine, made a statement criticizing President George W. Bush onstage during their European tour. A few days later, program directors at radio stations around the country received a memo prohibiting them from playing any Dixie Chicks songs on-air until further notice. This memo came straight from Tom Hicks, Vice President of massive media conglomerate Clear Channel. Hicks, who frequently did business with President Bush, was his neighbor in the exclusive gated community of Preston Hollow in Dallas, TX. On the controversy, the former president remarked,

“The Dixie Chicks are free to speak their mind. They can say what they want to say…They shouldn’t have their feelings hurt just because some people don’t want to buy their records when they speak out.”

Clear Channel, owning more than 1,200 radio stations in 2003, dominated the broadcasting market and thus had the power to make executive decisions determining what millions of Americans listened to. The decision to keep the Dixie Chicks off the air wasn’t made by individual DJs; instead, Hicks held the final authority. After being blacklisted by Hicks, the Dixie Chicks did not perform or release music for 14 years.

If you’ve ever scanned through radio stations, you might be familiar with Ashlee Young‘s voice announcing, “You’re listening to Q93 New Orleans, your Hip Hop and R&B station.” Q93 is an iHeartRadio station, a product of 2014 when Clear Channel rebranded to the more personable-sounding name iHeartMedia. The media company owns 31 radio stations in New Orleans, holding sway over more than 25% of the available FM channels in the city. But iHeartRadio isn’t the only media titan in New Orleans’ airwaves. Across the nation, ten parent companies control a significant two-thirds of the radio market, with Clear Channel (now iHeartMedia) and Paramount Global collectively raking in 45% of the market’s annual revenues. In New Orleans, a mere 15 out of 39 available radio channels are locally owned and operated.

President of iHeartMedia Tom Poleman posing at their headquarters in New York

Source: User Angelica555 via Wikipedia Commons

As her voice echoes across the New Orleans airwaves, listeners in cities like Atlanta, Houston, and Jacksonville also catch Young’s shows on their local Hip Hop and R&B stations. Young spins a track by Kendra Jae, one of the newest artists in iHeartRadio’s coveted “On the Verge” program. This program, created by executive brand managers at the company headquarters in New York City, handpicks five to six songs from rising artists. Nearly all these artists, typically introduced by the most powerful players in the recording industry, reflect iHeartMedia’s strategic partnerships with Universal Music Group, Sony Music, and Warner Music Group. The selected tracks are sent to their stations, mandating DJs to play each track at least 150 times over six weeks. A significant portion of iHeartRadio’s radio content is controlled by such top-down programs, often referred to as consolidated playlists in the industry. Consolidated content also extends to their talk-format shows, and as listeners tune in to their local stations to hear The Breakfast Club or the Steve Harvey Morning Show, listeners thousands of miles away are simultaneously hearing the show on their regional channels.

iHeartRadio float at New York Pride circa 2019

Source: User DVSROSS via Wikipedia Commons

The airwaves are a limited resource stations must compete for. Radio technology transmits by converting mechanical sound waves into far-reaching radio waves, allowing transmissions to be picked up by a receiver miles away. The range of frequencies that can operate within the radio spectrum is a fixed range, and the laws of physics impose a strict limit on how many frequencies can be broadcast at one time. To mitigate airwave congestion, individuals and corporations hoping to start a radio station must get a license from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the chief regulator of the broadcasting industry. As the radio industry began to dominate the media market in the early 20th century, President Calvin Coolidge signed The Radio Act of 1927, which deemed the radio spectrum a public utility because of its essential and limited nature. The legislation stated that licenses would only be granted to stations that met a rigorous “public interest” standard, requiring them to fairly represent public opinion and serve the interests of audiences in their geographic locale. Subsequent regulations in the 1934 Communications Act put limits on the number of stations one entity could control, and for nearly seven decades, the radio was localized, diversely owned, and strictly regulated to ensure public interest was protected.

This all changed with the 1996 Telecommunications Act, which eliminated previous caps on nationwide station ownership and dramatically increased the number of stations a single entity could control. The chairman of the FCC at the time, Reed Hunt, said in a speech that the objective of the overhaul was:

“Fostering innovation and competition in radio… but in our broadcast ownership rules we also seek to promote diversity in programming and diversity in the viewpoints expressed on this powerful medium that so shapes our culture.”

The period that followed the 1996 Telecommunications Act was marked by extreme consolidation in the industry. In less than six years, Clear Channel went from owning 40 stations to 1,240, nearly thirty times the number previously allowed by congressional regulation. The smaller the market, the more intense the consolidation, with the top four parent companies now controlling 90 percent of revenues in most regions outside of major cities, buying up local stations by the dozen.

President Clinton signing the Telecommunications Act of 1996

Source: Office of Congressman Ed Markey

Almost overnight, radio shifted from strictly serving public interests to considering profit margins, and commercial radio began packaging content to maximize income from advertising. Marketing executives started determining programming instead of local air personalities, and the most efficient way to gain broad listenership was shifting from narrow to broad appeal through consolidated playlists. In 2017, the FCC overturned its eighty-year-old requirement that stations must maintain a studio in their “community of license,” and local air personalities were left with limited opportunities for employment as their stations moved to corporate headquarters and their shows were cut in favor of homogenized content. After radio giant Cumulus bought out its competitor Citadel Broadcasting in 2011, becoming one of the top four owners of the market share, airplay for female artists decreased by 35%. Black station ownership has declined by 39% since the implementation of the 1996 Telecommunications Act.

Currently, the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB), a trade and lobbying group for the broadcasting industry (whose board includes chief executives from the top radio conglomerates, including iHeartRadio), is pressuring the FCC to adopt their proposal which would expand caps on how many stations an entity can own in a single city. NAB wants to allow conglomerates to own up to 10 FM stations in any of the top 75 markets in the U. S., with no restrictions on AM ownership or control over markets outside of the top 75. The proposal would allow companies like Clear Channel to amass even more control over the content we hear on the radio.

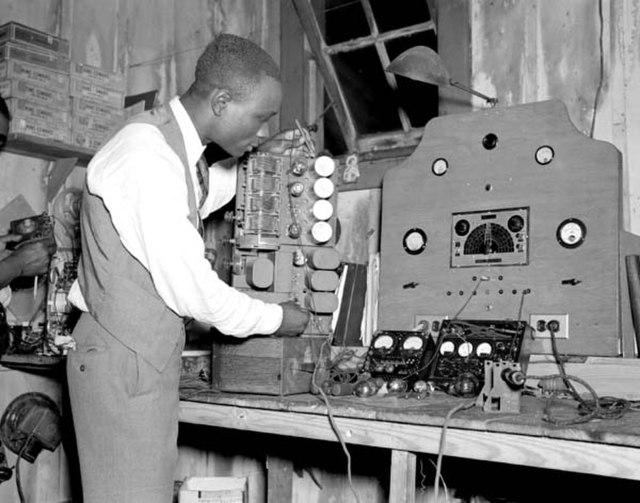

A student tinkers with equipment in a radio broadcasting class for black men in New Orleans circa 1937

Source: Wikipedia Commons

“New Orleans had the best radio stations in the world… Back then, when something was wrong the radio could lay hands on you and you’d be all right”

– Bob Dylan in his 2004 autobiography

Tony Peppers taps his keycard to unlock the sticker-covered door facing Orleans Avenue, the AC humming as he greets Mardell Culley, the General Manager. “Have a good show Peppers!” Culley calls out from behind his massive monitor. Tony passes through the green room and checks his mailbox, where a flyer for the Spring Membership Drive awaits him. The station depends on donations from members to continue operations, and the whole team of volunteer air personalities has been encouraging their listeners to contribute throughout the month of April.

The control board in WHIV 102.3 FM’s studio. Source: Claire Stephens

He heads into the booth, and the second the clock strikes 10 pm, he fades in a song by New Orleans native Dawn Richard, who’s set to play at Jazz Fest the following weekend. As the polyrhythmic electro-dance track wraps up, he puts on the bulky station headphones and flips the main mic on, “This is Tony Peppers live from Mid-City. You’re listening to the Electric Embassy on New Orleans’ only radio station dedicated to human rights and social justice, WHIV 102.3 FM.”

Founded by prominent infectious disease physician Dr. MarkAlain Dery, WHIV 102.3 FM is a mixed-format station dedicated to social justice and community advocacy here in New Orleans. Dery started the station to dispense essential information about HIV and other infectious diseases that disproportionately affect disadvantaged and marginalized populations. He knew radio was particularly powerful; the medium is still vital for low-income communities without reliable access to WiFi, and the equalizing FM tuner provides ample opportunities for new and returning listeners to tune in. In 2014, the FCC granted him a low-power (LP) license for the 100-watt FM station, and eight years later, they have more than 70 hosts creating over 12 hours of original content a day.

Pictured: Amy Irvin, host of ProFrequency (right), and Judge Calvin Johnson, host of NoiseFilter (left)

Source: Claire Stephens

Throughout the week, listeners can tune into a variety of activism-focused talk shows hosted by members of the NOLA community, which give information that you’re unlikely to find elsewhere on air, particularly in Louisiana. Though every air personality is a volunteer, their resumes are remarkable. Amy Irvin, co-founder of the New Orleans Abortion Fund, hosts ProFrequency, a show about reproductive justice where she directs listeners to STD testing centers, reports on new medical legislation, and even provides information on how to obtain an abortion in Louisiana. Retired Judge Calvin Johnson discusses criminal justice reform and the prison industrial complex on his show NOLA Matters every Wednesday morning. Dery himself has spent the past two years updating New Orleans residents on the pandemic and how to protect themselves amidst growing distrust of vaccines, masks, and the medical community on his show NoiseFilter. Throughout the day, the station also has traditional music shows that often highlight underrepresented and local artists.

In January 2000, following growing concerns about the deregulation of the 1996 Telecommunications Act, the FCC established a new kind of license, LPFM, for “low power” stations operating at no more than 100 watts. These licenses were granted to schools, non-profits, and educational organizations “to create opportunities for more voices to be heard on the radio,” giving birth to a small number of community radio stations that could broadcast up to a 3 ½ mile radius. A letter written to the FCC by prominent musicians like the Indigo Girls, Sonic Youth, and Bonnie Raitt, celebrated that, “Low Power FM radio stations will make it possible again to establish and manage stations out of love of music, not profits.” But today, LP stations are still few and far between and are mostly found in rural areas. In city centers like New Orleans, a more concentrated population means more potential listeners, making FM frequencies incredibly lucrative. Often, LP stations simply can’t compete against larger commercial firms in the highly competitive market and must fight for the funds to stay afloat. WHIV is one of the youngest LP stations in New Orleans, and, amidst the fierce competition of the market, their position is precarious.

WHIV General Manager Mardell Culley poses in the studio

Source: Claire Stephens

WHIV 102.3 FM depends on the support of its listeners, and while iHeartRadio forms mutually beneficial relationships with recording companies, they’ve had to form close relationships with the community they serve. In December, they hosted their 7th annual Community Voice Awards, where they honored the local organization Daughters Beyond Incarceration, which mentors young black girls in New Orleans with an incarcerated parent. Local distillery Seven Three Distilling Company provided beverages as New Orleans drag performer Vanessa Carr introduced the variety of local musicians performing. Music venues like the Starlight and Hi-Ho lounge sponsored the evening, where hosts, DJs, and community residents alike gathered to celebrate another transformative year on the air. The funds were used to fix the main monitor in the station and purchase a phone so listeners can call in and connect with air personalities.

Host Jonathan Jamison welcomes local band Single Malt Please into the studio to play a live set for “The Flow Show” Source: Claire Stephens

An art piece in the station signed by staff Source: Claire Stephens

Amidst the corporate radio oligopoly and the state’s conservative political landscape, listening in to the unapologetic politics WHIV broadcasts feels truly subversive. With locally sourced programming and hosts whose only compensation is personal gratification, the content on 102.3 FM wouldn’t be possible without passion. Individuals in the community come together to step up and shine a light on forces of oppression in one of the most impoverished metros in the U.S., giving information on-air that directly undermines the state government’s conservative agenda and exploitative corporate interests. If this isn’t the public interest the FCC was created to protect, what is? A report by Future of Music found that 80% of survey respondents supported government action preventing further radio consolidation, with 75% saying they would welcome homegrown LP stations in their community. “Community radio stations can preserve, define, and nurture the cultural ideas that make communities unique,” writes Professor of Communications Vanessa Murphee.

The most efficient path to diversity, localism, and the protection of free expression on the air would be an overhaul of the 1996 Telecommunications Act and a dissolution of the radio monopoly market, but this seems unlikely considering the government hasn’t been willing to make moves to end conglomeration since the Act was signed into law. But even if a complete overhaul is impossible, the FCC could impose a quota system that would reallocate high-power commercial licenses when they come up for renewal and grant them to new low-power stations instead, empowering individual citizens to get on the air. By mandating an equitable ratio of commercial-to-community licenses, the government could ensure a balance of diverse localized content and would ease the unnecessary burden on existing LP stations to compete in the cutthroat commercial market. But until that happens, perhaps the best thing we can do as citizens is support the stations within our own communities that work to democratize and diversify the airwaves, and who can temporarily relieve us from big corporations’ control over the ideas expressed on one of our most powerful, dear, and limited natural resources: radio.

WHIV’s logo, featured on the studio wall

Source: Claire Stephens

We’re not a radio station with a mission, we’re a mission with a radio station.

– WHIV 102.3 FM mission statement

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.