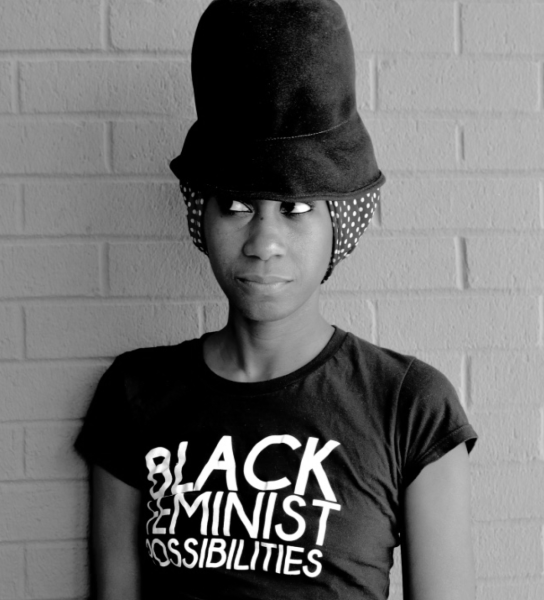

Shana Griffin, the founder of PUNCTUATE and DISPLACED, is a feminist activist, independent researcher, applied sociologist, artist, and geographer. She has founded and upheld a variety of projects that aim to showcase different racial disparities throughout New Orleans. Shana’s research mainly centers around the different experiences of Black women; however, in a larger scope, her projects and art practices showcase the lived experiences of theBlack Diaspora.

Homeless encampment under the Pontchartrain Expressway, New Orleans.

Racial segregation in regard to residential housing in New Orleans began in the 1920s and further increased in the 1930s. The urban landscape in New Orleans was designed to be discriminatory and exclusive under racially restrictive covenants and zoning ordinances, New Deal housing policies, local government blight and slum clearance initiatives, and real estate and banking practices. Specifically, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation Act, the National Housing Act, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), and the Housing Act, lead to the establishment of redlining maps, which institutionalized racial residential segregation. The establishment of the Housing Authority of New Orleans mixed with coordinating and financing the construction of housing developments in urban settings created the foundation for the displacement and relocation of low-income Black residents within public housing. These acts codified racial residential segregation and the social positioning of the Black community and particularly low-income Black women, aiding the justification of the mistreatment and discrimination the Black community faced in public housing. For years the majority of mortgages written by the FHA supported only white families, while private banks restricted their help and discriminated against Black families seeking assistance for their mortgages.

The displacement and confinement of the Black community created racially and economically segregated neighborhoods. Low-income Black women found finding a place to live in the dynamic housing market difficult due to racial and gender stereotypes and biases that inhibited them from equal treatment, which eventually restricted them to public housing. The lack of opportunities and possibilities, bad affordability and surveillance, and the prominent restrictions and discriminations encouraged the low-income Black women to come together and organize to reform the lives of public housing residents. Their initiative for reform included but was not limited to challenging poor maintenance policies, fighting against illegal and unfair evictions, sponsoring neighborhood clean-ups, developing recreational and after-school enrichment programs, organizing against police brutality, establishing community centers and resident management corporations, creating work opportunities for residents, partnering with local groups establishing child care centers and health clinics, hosting cultural events, advocating for safe and healthy housing conditions, and working daily to address the impact of economic and housing-related poverty, violence, and substance addiction. The fight for reform within the discriminatory and racially segregated public housing was a fight that was marginalized in the historical contexts of Black freedom and women’s liberation movements.

Reforms in public housing were given a chance to dismantle centuries of racist housing practices that provide the framework for the fortified segregation still prevalent in the city’s neighborhoods after Hurricane Katrina. By the time Katrina hit and the levees broke, flooding the city, the extreme poverty areas were majority populated by Black residents, and these neighborhoods, like the Lower Ninth Ward, were the ones that endured the brunt of the natural disaster. One Lower Ninth resident Burnell Colton mentioned how, “[they] didn’t have no stores, no barbershops, no laundry rooms, you have to catch three buses to get to a store.” The disproportionate damage was due to low-income neighborhoods being redlined into below-sea-level districts and wealthier neighborhoods being placed in high-ground districts. After the natural disaster, $142 billion in federal funds were funneled into the city, yet many policy decisions made during the recovery repeated and amplified the existing patterns of separation and inequality, and continued to deny people of color mortgages at higher rates than white homebuyers. Even as recent as 2018, the New Orleans City government has failed to require developers to include any affordable housing units in an up-and-coming neighborhood on high ground. The destruction that riddled the neighborhoods in New Orleans displaced 600,000 households, but yet parishes continued to restrict affordable housing and rentals after Katrina.

Shana Griffin

Shana Griffin recognized these disparities that were established in 1934 yet still affect New Orleans communities today, and Griffin created an interactive timeline to trace back the geographies of black displacement, dislocation, containment, and disposability in land-use planning, housing policy, and urban development in the city as a form of activism and protest. The injustices that were ingrained into society from 1934 are the same discriminatory policies that keep housing and neighborhoods segregated. Her collaborations with galleries, forums, and initiatives, aided in her exhibits at the Contemporary Arts Center New Orleans that featured her piece: DISPLACING Blackness: Cartographies of Violence, Extraction, and Disposability of the DISPLACED Project. Her activism towards calling awareness to the discrimination and disparities in New Orleans housing through her multimedia feminist and public history project has helped illustrate the changes that need to be made to ensure progress from policies implemented within the city’s neighborhood structures.

The City of New Orleans and the Housing Authority of New Orleans created a plan, submitted in October 2016, which outlines strategies for making housing options in the city are more equitable. HANO is taking steps to improve its housing voucher system, including allowing for more flexibility in pricing rent at the ZIP code standard and working with housing advocates to recruit landlords. However the steps being taken to try to rectify the redlining are slow, and the problem will not go away overnight.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.