Overworked woman. (Photo by: Wikimedia Commons)

Workaholism (the concept that constantly working can be understood as an addiction) was developed and defined in 1971 by psychologist Wayne E. Oates, who referred to “an uncontrollable need to work incessantly”. Many may identify this “obsession” as a positive drive that motivates young professionals to thrive in their profession. Workaholics have a “common defense: that they love their jobs.” Compared to other addictions that are “socially disapproved of like alcoholism, workaholism is often viewed positively,” with 48% of Americans identifying themselves as modern-day workaholics, and only 28% claiming that they are workaholics out of financial necessity. This discrepancy reveals that for many, the drive to work goes beyond monetary growth or passion, and is much more tied to an internal pressure that limits one from disengaging from work without feeling tremendous guilt.

Workaholism is only possible because we live in a country that thrives on a “religion of workism.” There exists a belief that “employment can provide everything we have historically expected from organized religion”: social acceptance, happiness, health, safety, and success. In the Western world, there is a connection between success, represented by wealth and possessions, being directly tied to work. This connection makes possible the idea that those who do not work are “lazy.”

With the US being the “most overworked developed nation in the world,” with citizens working an average of 8.28 – 9.05 hours per day, workaholics can be almost indistinguishable from regular workers, and they may even appear inconsequential. However, the distinction is quite important. 763 employees were studied in a 2020 Harvard Business study, which found that “work hours were not related to any health issues, while workaholism was.”

The behavior of those who work long hours is not as harmful as the mentality of workaholics because such a mental state makes one unable to “psychologically detach from work” and remain in a cycle of stress, anxiety, depression, and sleep problems. This harmful living style continues when people are unable to recognize the early signs of workaholism: perfectionism, a schedule consisting of only work tasks, difficulty developing or maintaining social relationships, anxiety and guilt when doing activities other than work, ignoring the urge to eat or sleep, and low self-esteem. Self-diagnosis through recognition of such traits can stop the accumulation of the social, physical, and professional consequences of being a workaholic.

Working non-stop hours can actually stall productivity due to heightened exhaustion. A recent study found that people who work 70 hours per week didn’t actually get more work done than those who worked 56 hours. Physical health factors such as back pain, strokes, coronary or artery disease, type 2 diabetes, and even cancer have been tied to a hormone called cortisol which is released during work stress. Additionally, those who logged 11 hours per day were more likely to battle depression than those who logged 8. Depression, exhaustion, guilt, and physical pain, in addition to an overall sense of having “no time” outside of the workplace, are all symptoms of overworking that can take a negative toll on relationships. A life that is 80% work with little time to enjoy the “small, fleeting, but significant moments and gestures” leads to poor health outcomes and less personal fulfillment.

But, hey, let’s stop focusing on the “meh” and get to the top hacks for a workaholic.

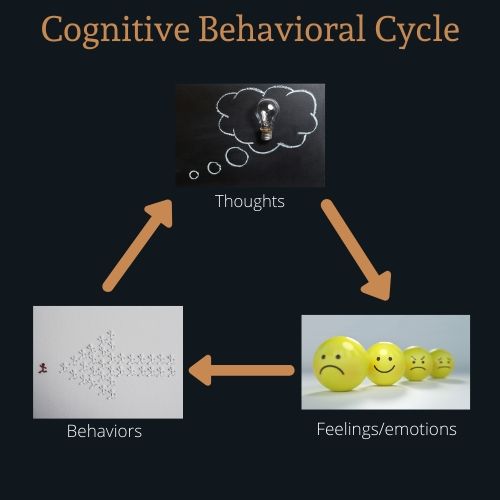

Workaholics often love their jobs and are passionate about their careers; this passion, however, paired with possible low self-esteem and the 10.4% of Americans working an average of 50 + hours fuels an environment where 57% of workers view themselves as having a poor work-life balance. Changing one’s relationship with work to allow for more social activities requires a change in mindset and an alteration of habits. These changes have to occur through direct engagement with the issue, rather than evasion. One strategy is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy ( CBT), which forces one to “recognize negative or unhelpful thought and behavior patterns” and learn coping strategies. CBT methods can change one’s thinking and ways of coping, with strategies ranging from moving to a new location with a positive work balance, taking small steps to change one’s workaholic mindset, and creating a schedule or listing system that ensures productivity only during working hours.

Bergen, Norway (Photo by: Wikimedia Commons)

Method 1 : Change Your Environment

What?

“Americans ‘live to work’ while we ‘work to live,’’ is a phrase often passed around by non-Americans as a reaction to the workism ideology. This ideology is based on the belief that work is not just a means of economic production but is also the center of one’s identity. Americans have been found to work 184 more hours per year than Japanese workers and 300 more hours per year than U.K. and French workers, revealing an overall lack of value in life outside of the work sphere. A poor work-life balance affects one’s health, with 79% of employees experiencing work-related stress which hinders them from enjoying any free time. European countries hold the top rankings in the World Population Happiness scale, as a result of many countries’ public benefits: public healthcare, retirement funds, education, high-speed rail systems, paid vacations, more PTO, etc. Changing one’s workplace environment by moving to another country, such as Norway, that values free time could improve one’s work-life balance. It seems Norwegians are aware that working more hours does not actually mean one is improving their skills or status because “out of an eight hour work day, workers are only productive three of those hours.”

How?

With a 7.365 out of 10 rating for happiness, Norway has a work-life balance built into the country’s guidelines for workers’ rights. The Norwegian Working Environment Act includes provisions for the work week, flexi-time, vacation, office social relationships, and time off. The typical work week is 37.5 hours, meaning less than 8 hours a day to be dedicated to work. In the case of working overtime, there is a minimum of 40% extra pay, ensuring people are receiving proper payment for their work. The “kjernetid” or “core hours” are to be held daily in the workplace from 9 – 3. Additional time is known as the “flexi-time” system, where employees may work wherever they wish outside of the workplace, making clear that “ always working later than your boss is not compatible with the Norwegian work culture.” Synne Lüthcke Lied, employment attorney, states that “you can’t work 14 hours a day, 7 days in a row. That is actually illegal.” The importance of rest in the workplace is also apparent in the 5 weeks each year that are dedicated to vacation. Beyond legal regulation, the social environment within the workplace, known as “Kantinepris”, is very important. Kantinepris is maintained through catered lunches with coworkers, a supportive office community, and a break in the day.

Why?

Living in Norway, one will work an average of 42.9 hours per week—1.4 hours less than full-time jobs worldwide. You will be able to live with a new mentality of work-life balance that is mostly absent in the United States, where “55% of workers get a sense of identity from their job.” Not only will working fewer hours “improve health and greater life satisfaction,” but it also places greater emphasis on spending time with people you care about.

The cognitive cycle of a workaholic. (Photo by: Leah Bohatch)

Method 2: Change Mentality

What?

Internal and external factors build an atmosphere in which workaholism thrives. Motivational, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral factors create a mentality around working that affects all aspects of people’s lives. These factors can lead to a sense of guilt inside and outside of the workplace, making it “difficult to mentally disengage from work.” In recent years, the social and domestic spheres have become less separated from one’s workspace. 7 in 10 Americans answer work-related messages outside working hours. The constant cycle of workaholism, known as “the addiction that society applauds,” is often not acknowledged until one hits the bottom. At this point, simple acceptance of workaholism is not enough—mentalities must be changed with a stepped program focused on leading a productive, well-balanced life. A stepped program targets the “psychology of the participant,” and goes far beyond simply acknowledging the problem. One is able to achieve a change in their daily behavior and operation by breaking the process into 12 smaller steps. This makes coping with workaholism “easier to manage” and helps people “avoid being overwhelmed.” A stepped program leads to a reorganization of one’s life that will effectively change the way one interacts with work and life balance.

How?

The 12 Steps of Workaholics Anonymous

Why?

By addressing work addiction and taking small steps, one’s newfound appreciation for work-life balance will result in more time for “things and people who matter most to you.” Deconstructing one’s workaholism by addressing the effects on one’s mentality will has the capacity to remediate the past alienation of loved ones.

Prioritizing Tasks with a To-Do List

Method 3 : Change Work Habits

What?

Long work hours and the constant pressure to be productive are linked to people’s mounting anxiety and an “obsession with pressing tasks,” according to psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik. This issue, known as the “Zeigarnik Effect”, decreases productivity, as observed in a 2011 study in which participants became increasingly worried by incomplete tasks. This anxiety resulted in “intrusive thoughts and inhibited completion of further tasks.” During an additional recent study, Professors Baumeister and Masicampo of Wake Forest University stated that “simply writing the tasks down will make you more effective.” David Allen, author of Getting Things Done, writes that “a system is needed, and scribbled notes on hands won’t cut it,” because if your list “isn’t clear, your tasks probably won’t get done.” With a detailed, broken-down list of daily tasks, Americans are able to complete 69% of their weekly tasks.

How?

Each individual’s schedule and time management style is correlated to their specific “circumstances, personalities, and energy levels.” Thus, each person will probably need different coping strategies to help with work stress. There are a variety of different strategies, ranging from flexible to more strict depending on the needs of each person.

Those who need to work under a strict time limit or who thrive when given a deadline may utilize the Time Blocking Method. One’s tasks will exist in time blocks of proactive and reactive blocks where hours are divided between focus and originating ideas and reacting to requests, such as emails. This worker will be able to work with extreme focus as they know “exactly when they’re going to accomplish a specific task,” compared to the less productive “to-do list that leaves one with too much flexibility.” Planning your work week at such a detailed level can generate high levels of productivity. According to productivity guru Cal Newport, “a 40-hour time blocked work week produces the same amount of output as a 60+ hour work week without structure.”

Productivity expert James Clear explains that many fear jumping into the most important task first, and as a result begin to waste hours by “crossing off the 4th, 5th, or 6th most important task on their to-do list.” To combat this tendency, the Most Important Task Method (MIT) sets up 1-3 tasks per day that are essential, and thus all other tasks can become “ secondary or even unnecessary.” Working in short, active bursts according to a dedicated task list, followed by quick breaks, can increase focus without complete “mental fatigue.” The Pomodoro Technique includes 25-minute constant work sessions followed by 5-minute breaks, resulting in manageable intervals and adequate rest. With repeated intervals throughout the day, including longer 30-minute breaks after 4 sessions, one can “get more done with two sessions than in the other seven hours of the work day.” A 1993 study about the body’s ultradian rhythm (the body’s natural rhythm during daytime) reveals the need for rest as “essential for improvement” because the body tends to fluctuate between crashes and intense work sessions. By planning one’s work in relation to one’s “maximum energy levels,” ineffective working periods can be avoided. The 90-minute focus session makes efficient use of energy peaks and troughs, illustrated in the 20 – 30-minute rest period.

Why?

70% of working Americans stated “ that they never have enough time,” but by detailing plans through a list or schedule, “precious hours in the day can be protected.” By increasing efficiency through scheduling methods, a sense of productivity will be felt by the worker and more free time will be allocated for social interaction, which will increase health and happiness.

All of this sounds great, but the big part is actually implementing these strategies into your life; find below some resources to help you with this work-life shift!

Free Apps:

Free Videos:

This piece was edited by Lily Plowden as part of Professor Kelley Crawford’s Digital Civic Engagement course at Tulane University.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.