For many seventeen year old boys, the question of “will I have my lunch period with friends?” presents as the most pressing matter of the semester. For seventeen year old Juron Newman, however, the question of “will I find anyone my age in this cafeteria?” seemed to be a more relevant question. Yet, looking around the four walls of the Orleans Parish adult prison that detained him, Juron realized that finding other young Black teenagers in this cafeteria to sit with wouldn’t be difficult.

When Juron was arrested in 2018 for allegedly taking a woman’s cell phone during an argument and firing a gun into the air, he assumed he would be tried in New Orleans juvenile court. As Juron awaited his court date for months locked in a cold jail cell due to his highly priced bail, he worried about what the future held for him.

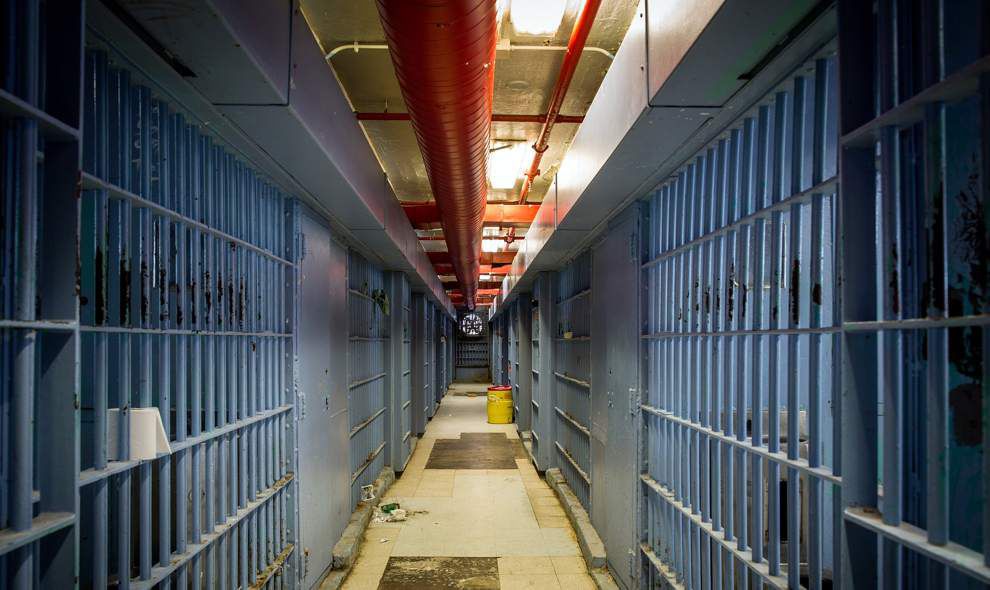

A hallway in New Orleans Parish Prison (Photo by: The New Orleans Advocate)

This inability to pay bail was not unique to Juron, but rather a reflection of the racial disparities in the system. In New Orleans, Black people are arrested at severely disproportionate rates to White people while simultaneously earning only 37 percent of what White families earn. In result, in 2018, eight out of ten New Orleans juvenile felony defendants held in jail due to an inability to pay bail were Black. During this waiting, Juron’s lawyer reminded him of the benefits to his age in the criminal justice system, and the rehabilitation and education services offered in juvenile prison. Eventually, Juron’s court date arrived.

Quickly upon reviewing Juron’s case, Orleans Parish district attorney Leon Canizzaro made the decision to transfer juvenile aged Juron to adult court.

While this was a shock for Juron and his family, this decision reinforces the pattern of transfers Cannizzaro has historically made as district attorney. Throughout Canizzaros twelve years in office, only one young person he transferred to adult prison was not Black. Yet, in the past four years alone, 100 percent of the youth he’s transferred to adult prison have been Black. This racism does not begin at the transfer, however, as more than 95 percent of juveniles arrested in these past four years have been Black. Rachel Gassert, policy director of the Louisiana Youth Justice Coalition notes “What the New Orleans system shows us is the only children who are arrested in New Orleans are Black, so the ones who face the harshest punishment are Black.” After this transfer verdict, Juron’s lawyer advised him to plead guilty, despite Juron’s denial of the crime. This is the reality for 96% of convictions in juvenile cases transferred to adult court in New Orleans, as the fear of receiving a longer adult sentence outweighs the desire to fight for a just verdict.

The prosecution provided little evidence proving that Juron committed this crime. However, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, in transfer cases “the [defendant’s] alleged offense is the deciding factor” regardless of the evidence, or lack thereof, provided. Sitting in that courtroom, if Juron had asked his lawyer if this decision could be reversed, his lawyer would have informed him that unlike the twenty four other states with “reverse waivers,” Louisiana law mandates that once a child is transferred to adult court, a judge cannot reverse the transfer. Additionally, regardless of the judge’s assessment of Juron’s individual fitness for adult court, Canizzoro, who has never met Juron, is the only decision maker in this process. Maybe Juron was looking around the courtroom at this moment for a friend to hug, a parent’s shoulder to cry on, or even a teacher to insist that “Juron has a test Monday and won’t be able to make it to prison!” but these support systems are stripped from young Black teenagers in New Orleans from the moment they enter this adult system. Juron was alone, left to face a new reality in which he no longer would be seen as the child he was.

After his conviction, Juron was put on a bus and taken to Orleans Parish Prison.

Incarcerated young people in Orleans Parish Prison (Photo by: Richard Ross)

These transfers imply that the nature of these children is so irredeemable that this transfer is their only option, when in reality, there is no worse option for a child in the criminal justice system. Walking into those doors, Juron didn’t realize the danger his age presented on both his emotional and physical well being. In New Orleans adult prisons, young people are twice as likely as those in juvenile detention to be physically assaulted by staff, and five times as likely to experience sexual assault. While Juron may have previously resented the early wakeups for school, the majority of children in the adult prison system yearn for a semblance of normal education. Learning, unfortunately, is a sacrifice these adult transfers force children to make. In New Orleans adult prisons, young people like Juron often serve the same amount of time as they would in juvenile prison, but the services offered in Juvenile prison that rehabilitate, educate, and prepare them for successful re-entry into the community are not offered. While Louisiana adult prisons often allow vocational training and GED programs, these programs have been proven ineffective in providing the skills necessary to a young person’s development. With a lack of access to these services during critical brain development periods, the gap slowly narrows for young people to develop these critical skills.

While Juron has yet to be released from Orleans Parish Prison as of November 2020, many young Black men with similar stories face harsh realities after their release. Often, the first goal post incarceration is to get a job. However, with no resume, a lack of formally developed social skills, and an incomplete education, this proves difficult for juvenile transfers. Additionally, finding housing post incarceration presents as another barrier. Currently, the Housing Authority of New Orleans broadly denies housing to any person who has a criminal record “involving criminal activity which presents a threat to the health, safety, or peaceful enjoyment” of other residents.” Without access to housing, work, or rehabilitation from the prison system, many juvenile transfers know only what they learned in prison during these crucial social and emotional development periods. Overwhelming research suggests that teenagers prosecuted in Louisiana’s juvenile justice system are less likely to reoffend than those prosecuted in the adult system. Meaning, prosecuting children as adults increases the likelihood that they will end up behind bars again. Due to a combination of his race, his development, and his lack of support, when Juron is released, he will need to defy the odds in order to not end up in Orleans Parish Prison once more.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

[…] Story continues […]