As of 2013, African American members of the New Orleans community were three times more likely to die from diabetes and twice as likely to die from HIV or kidney disease compared to its white community. The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted these racial health disparities, with a national COVID-19 mortality rate of 6.8 per 10,000 for Black people, and only 1.5 for White people. Louisiana, specifically, has notably higher Black mortality rates. Looking back to New Orleans in the 1840s, Todd Savitt writes about how the “open and deliberate use of [B]lacks for medical research and demonstration well illustrates the racial attitudes of antebellum white southerners.” A survey of 222 white medical students today revealed that half of them believed there were physiological differences between Black people and whites. The mistreatment of certain populations in the medical field stems from years of racial attitudes towards Black Americans, evident in the abhorrent and unethical Tuskegee Syphilis Study that spanned from 1932 to 1972. Medical professionals in the late nineteenth century believed that emancipation had a lasting deteriorating effect on mental and physical health. However, Savitt states that “Negroes did not seem to differ enough from Caucasians to exclude them from extensive use in southern medical schools and in research activities.” These attitudes persisted because “medical science helped to explain and defend the prevailing social structure of early nineteenth-century America.”

The very first New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal, published in 1844, aimed to “elevate the Medical profession from the State of a mere money-making trade; to its proper position, the noblest pursuit that ever engaged the attention of man!!!” It is considered one of America’s earliest medical journals. When discussing professors of medical schools in this journal, Carpenter questions them, wondering if “they too assumed the awful responsibility of becoming teachers of medicine for the sole and degrading object of making money?” It was written not only to alter the monetary path of medicine but also because “[m]ost of the Diseases”… “have rarely been seen by the Teachers of the North.”… “it is in the South we must study Southern Disease.” Given America’s vastness and diversity, medical professionals needed a different approach compared to countries like Spain or France, where most medical knowledge at the time originated. Common treatments for Southern diseases, such as scrofula, king’s evil, or mercurial disease, began to shift toward vegetable-based medicines, especially in 1841, with multiple variations advertised in New Orleans’ local newspaper, The Daily Picayune. Previously, mercury-containing concoctions were a common prescription, referred to as, “injudicious treatment or juvenile irregularities,” leading to many mercurial-related ailments. Without proper regulations or knowledge, such as the modern day FDA and advanced technology, doctors often caused more harm than good.

In the 1840s, white men constituted the entirety of the medically trained community, referred to by Carpenter as a group of “united gentlemen.” Women would often aid in childbirth, and the first ‘nurses’ learned their skills by observing physicians. For the treatment of Yellow Fever and other ailments, many physicians as of 1843 believed in purgatives, also known as laxatives. They also held the belief that yellow fever, and many other prevalent diseases at the time, stemmed from the accumulation of excess blood, impeding proper circulation, leading to the common practice of ‘bloodletting’. Doctors often relied on their “best guess” when treating patients. This lack of medical knowledge prompted further experimentation, particularly at the expense of the Black community.

Illustration of Patient Receiving Bloodletting Treatment (Photo by: National Geographic)

Many enslaved people partook in“dirt-eating” and consuming other inedible materials, perceived by the white medical community as an act possibly committed for suicide as it led to severe gastrointestinal issues. It was often viewed as an instinctive or medical ailment by the white medical community rather than a form of suicide. In the 1800s, a plantation in Jefferson County experienced a typhoid dysentery epidemic where “European methods of treatment had been used on the blacks without success.” Another common ailment of the African American community, termed “Struma Africana,” was erroneously considered a hereditary disease unique to the African American population but was known in the white community as tuberculosis. Years later, it was finally recognized as the same disease. When discussing yellow fever, “it is but seldom that we hear [N]egroes being attacked,” by the disease. There is no discussion as to whether this is due to differences in population interactions or if enslaved people at this time were simply unable to express their ailments in the same manner as white people. It is stated that “[m]any planters, of course, seldom consulted the physician on the diseases of the [B]lacks.” Racial prejudices intertwined with the beliefs of medical professionals, combined with mistreatment and disregard by slave owners, led to many discrepancies in treatment. Lack of medical knowledge paired with racial prejudice caused numerous misconceptions in the medical community.

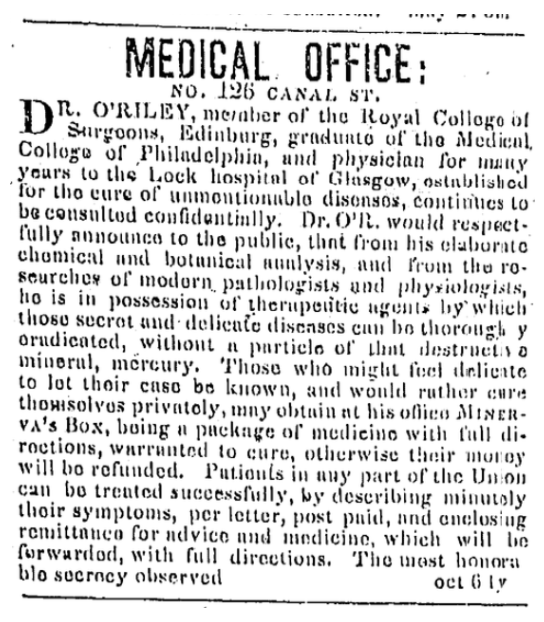

Dr. O’Riley, who practiced at 125 Canal St., offered his medicines to “patients in any part of the Union.” However, Union members were not the only population to receive special medical treatment in the South. Enslaved people also received medical treatment at the same facilities as whites in 1841 New Orleans, with Circus Street Infirmary charging only $1 per day for enslaved people when admission fees could reach up to $5. This fee covered all expenses during the visit, excluding surgeries, which incurred an additional cost. With the increase in medical students in the 1830s and the rapid growth of medical treatment surpassing its knowledge, there was a growing need for more patients for study. Southern institutions, such as Atlanta Medical College, even “encouraged owners to send their sick and injured slaves to the infirmary for treatment.” Not only was this practice encouraged, but some southern hospitals offered reduced or no fees for Black or enslaved patients to use them as learning tools.

Advertisement for Dr. O’Riley’s Medical Services (Photo by: The Daily Picayune)

To advance their knowledge, the medical community conducted experiments and used cadavers to teach anatomy, and during this time, the dehumanized enslaved African Americans were often the subjects. In the three decades leading up to the Civil War, “[c]ompetition for students among southern medical schools was fierce,” leading to a dire need for bodies to study. In lower southern hospitals during the mid-1800s, specifically in the late 1850s, Black patients, “were reserved for the exclusive use of student doctors.” The demand for cadavers was so high that physicians and students resorted to grave robbing, hastened dissections before bodies were claimed, and deception to obtain cadavers for autopsy and anatomical investigations. Human cadaver dissection was illegal in many antebellum states and perceived as violent and gruesome. Consequently, “Southern [B]lacks, because of their helpless legal and inconsequential social positions, thus became prime candidates for medical-school dissections.” Several state legislatures proposed bills to protect White bodies and even “to authorize and require the Judges of the different Circuit Courts of this state to adjudge and award the corpses of [N]egroes”… “for dissection and experimentation.” Such mistreatment understandably instilled great fear of doctors in the Black community, with rumors of doctors, known as “night doctors”, purposefully killing Black patients for medical investigations.

In the 1840s, medical professionals were the first to examine the Black community. A lack of medical knowledge and racial prejudices led to mistreatment, with doctors even convincing each other that Black and white people with the same symptoms suffered from different ailments. However, during this time, the Black community was not considered different enough from white people for the study of their anatomy or ailments to be considered useful. The idea that they later had different physiology or “thicker skin” only served to maintain racial prejudice and the social structure of the 19th century. Medical professionals of the mid-1800s were the first to examine the Black community, thus playing a pivotal role in upholding and instilling racial prejudices for their benefit.

This piece is part of the “Archive Diving for Future Clarity” series for the Alternative Journalism class taught by Kelley Crawford at Tulane University.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.