The first thing you notice when you step out of the hazy, humid New Orleans streets and into Faulkner House Books is the silence. We hear murmuring from time to time, but this murmuring seems to be intentional in its quiet volume. One or two conversations between a female store clerk and male customers can be heard in the recording, but even these conversations between the shopkeeper and her customers aren’t conducted at a ‘normal’ speaking volume; they’re on the quieter side, bordering on unintelligible at times. It’s clear that the natural state of order in this place is silence, and any noises we hear simply function in the background.

Photo by Cameron Liquori, outside of Faulkner House Books

It’s extraordinarily commonplace for retail venues to play music through speakers, in order to maximize customer comfort as well as to establish a “mood.” According to an article published by Psychology Today, music can create intentional atmospheres and moods, and humans have an emotional reaction to music (1). As this recording took place in a store without any background music, the silence of this space is therefore intentional. One must then pose the question: Why do we have cultural spaces that value silence?

“There is something mysterious about silence which connects us with each other and with nature beyond the structural definition and limitation of words (2).” Particular public spaces choose to emphasize silence for a reason. Take museums, for instance; a classic example of a cultural gathering space with an atmosphere of quiet. As stated by author James Heaton in his article titled “Music in Museums,” “Almost any audio-based work is going to invade other parts of a museum and therefore interfere with other works of art (3).” Music blaring through speakers would doubtlessly impede upon the viewing experience of museum patrons, distracting from the museum’s main focus; the art lining the walls. A bookstore is truly not so different from a museum in this respect. The focus of Faulkner House Books is to create an atmosphere where books can be perused and enjoyed without interruption. The absence of auditory stimulation emphasizes the visual and imaginative stimulation provided by the books themselves.

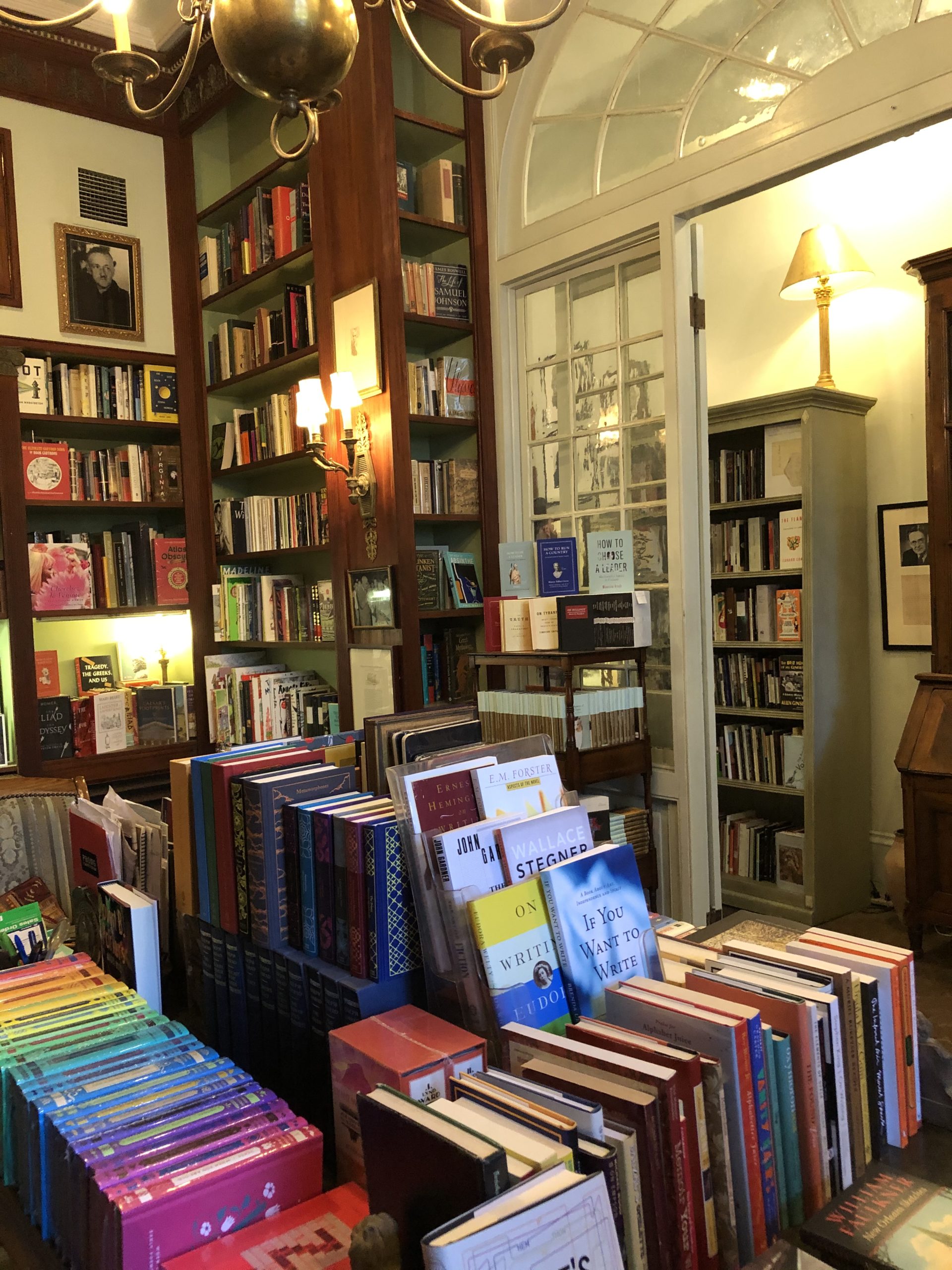

Photo by Cameron Liquori, inside of Faulkner House Books

However, to take this analysis a step further, I suggest that the silence of Faulkner House Books runs deeper than how it may appear. It’s true that background music may distract and detract from a customer’s experience browsing various books. However, the silence of this store can be connected to William Faulkner’s own experiences living in New Orleans and writing his first two novels in the early 1920s. Just as silence can be an unfamiliar and uncomfortable atmosphere that prompts the individual to be truthfully alone with their thoughts, William Faulkner’s time spent in New Orleans was the breach from his comfort zone he required to deconstruct the depths of his own ego and create new worlds inside his first published novels.

To define what I mean by ‘ego,’ the ego is a spiritual expression that humans use to defend the concept of individuality (4). Our ego is our deepest self. It’s what sets humans apart from each other; the innermost mechanisms of our thoughts and needs that constitute our identity.

In our daily lives, we open the contents of our ego to others through the thoughts we choose to express. One must be aware of the limits of their ego to express themselves honestly. The ego can never be truly “killed,” so to say, but it can be “transcended and made conscious so that it’s no longer running our lives (4).” To deconstruct your ego is to deconstruct every mental predisposition and barrier in your mind, transcending the boundary between the individual and the natural world.

In order for Faulkner to write his first novels, he had to effectively leave behind everything he knew. To create new worlds inside of novels requires a deep understanding of the natural world that cannot be achieved through a lifetime spent in familiarity. Besides a brief military stint in Connecticut, Faulkner previously spent his whole life in his home state of Mississippi. New Orleans was the first place where Faulkner could escape the bounds of what he saw as familiar and comfortable. And so, just as the silence of Faulkner House Books de-emphasizes individual vocal expressions to highlight the thousands of books lining the walls, the carefree and buoyant culture of New Orleans acted as an unfamiliar and silent slate on which Faulkner could examine and deconstruct the depths of his own ego, allowing him to push the boundaries of his imagination in his first two novels (5).

The brief conversation overheard about 23 seconds into the recording is indicative of the recording’s physical location, while also tying into the overarching history of New Orleans. The woman’s voice is friendly, but her words are routine. It’s important to note that her friendliness shouldn’t be confused with ease, as she doesn’t attempt to make superfluous conversation. She’s purposeful, following a ‘social script’ of sorts, going through the motions of completing the man’s transaction. In contrast, the man seems to be much more at ease. He makes casual, conversational comments to her customary questions, rather than simply giving the bare minimum ‘yes or no.’

For a moment, I propose we once again look back to the 1920s, when Faulkner resided in the heart of the French Quarter. (White) women gained the right to vote in 1920, granting considerable measures of power to this previously marginalized group. In New Orleans, the French Quarter preservation movement began to pick up steam in the late 1920s. The neighborhood had fallen into a state of overgrown disrepair, and New Orleanian residents knew that their neighborhood would soon face intense construction. Desperate to protect the history of the city, preservation-focused locals began buying property and reinventing the neighborhood, taking the power out of the hands of those who didn’t recognize the cultural significance of the preexisting structures. Women, in particular, played a vital role in this movement, creating groups such as the Vieux Carré Commission and the Vieux Carré Property Owners, Residents, and Associates for the purpose of preserving New Orleans history (6).

When this historical fact is considered in the context of my present-day recording, the curt and purposeful nature of the woman’s statements, as well as the carefree attitude of the male patron, takes on a new dimension. This woman is doubtlessly interested in the preservation of historical New Orleans monuments; if not, she wouldn’t be working at the renovated home of acclaimed author William Faulkner. She takes her job as both a bookkeeper and a keeper of information seriously, as the man’s response suggests she’s educated him in some form. In their exchange, the man plays the role of ‘just another flowery, languid resident of the Big Easy,’ and the woman plays the role of ‘historical preservationist,’ like so many New Orleanian women before her.

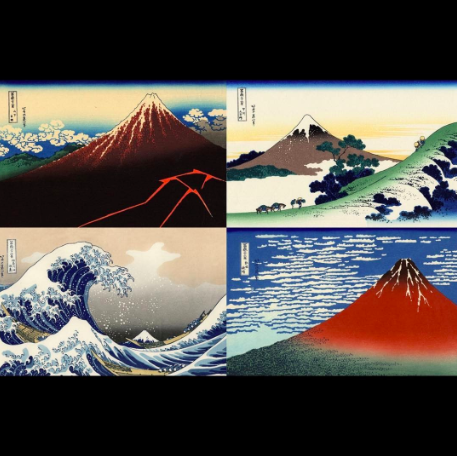

For my alternative format, I’ve chosen a previous work of nail art that I’ve done, featuring four of the thirty-six prints from Japanese artist Hokusai’s collection titled Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji. Hokusai created this set of prints at the age of 70, after a lifetime as an artist. This collection was his ‘magnum opus,’ growing to be his most famous creation by far. Hokusai was trained in printmaking, but for this collection he chose to forgo the typical printmaking process, utilizing disparate techniques he had gleaned from his decades of training while experimenting with Western art perspectives.

Hokusai likely underwent his own sort of ego deconstruction in the creation of these prints, moving away from the traditional process of Japanese printmaking in favor of a more intricate and complex multi-block process (7). Had Hokusai continued to create within his comfort zone, it’s unlikely that his works would’ve ever had the lasting global reach they still possess today. Only when an artist challenges themselves to abandon their comfort zone can they create works of art that leave a legacy.

This design challenged the bounds of my own abilities as a nail artist. For this design, I moved away from my typical medium of nail polish, and instead worked with acrylic paints, as they allowed me to be more precise and to blend the colors more smoothly. This is perhaps my most complicated and detailed work of nail art, and I wouldn’t have been able to achieve the result that I did had I not abandoned my usual medium in favor of trying something new.

Photo by Cameron Liquori, original nail art work

Four images from the collection “Thirty-Six Images of Mount Fuji”

WORKS CITED:

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.