When my mom told me that my grandma was orchestrating a book of letters to my recently deceased cousin I thought it was sweet, until I received my own barren, blank page in the mail. Hatred barely scrapes the surface of the emotions I felt towards this stark white piece of paper that sat perched on my desk, protected in a yellow envelope. Days of procrastination turned into weeks, which soon turned into months. I was petrified to open the floodgates. “To my sweet little baby David… ” I wrote. The simplest phrase, but the hardest one to get onto the page. He was fifteen, and the last time I saw him was when I still referred to him as “baby David.” I had missed some of the most pivotal years of his life; the years he transformed from the baby I knew to the adorable, lengthy, awkward, pubescent boy he had grown to be.

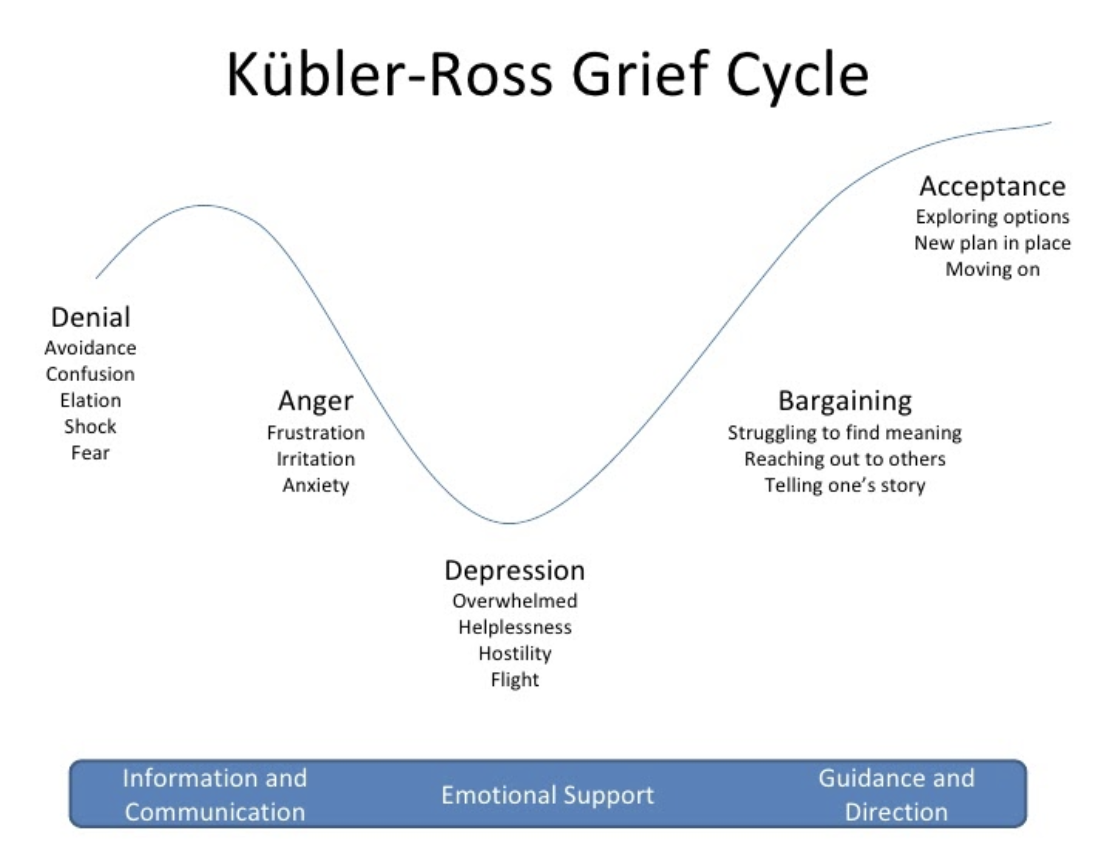

Despite its inevitability in human nature, death has the potency to engulf those experiencing loss. The process of making meaning of this dense, deeply perplexing plethora of emotions pushes psychological bounds and inflicts profound discomfort. Richard Gross, renowned psychology author, utilizes Kubler-Ross’s five stages of grief to articulate the psychological response humans experience after losing a loved one. The first stage, denial and isolation, prompts the second stage of anger. After anger comes the third stage, bargaining. Depression, the fourth stage, comes when the individual acknowledges bargaining efforts are unsuccessful in altering the permanence of death. Lastly, the fifth stage brings a sense of acceptance, allowing the intensity of grief to dissipate, returning a sense of normalcy to the individual’s life as a result of this closure (3). This framework of grieving lends itself to understanding the universality of psychological suffering, as a result of death, independent of intricate human difference and varying contextual circumstances.

A depiction of the five-stage grief process.

If grief could be understood solely by a five-stage process, it would arguably be easier to process. Grief exists as a highly discursive terrain. Author Robyn Ord, challenges hegemonic ideologies surrounding grief and seeks to understand the role culture plays in how grief is experienced. The functionality of grief as a discourse explains the way it is affected by definitions, perceptions and conceptualizations on what it actually means to experience loss (6). With culture at the center of policing grief, it regulates how its members mourn, subtly or openly, and dictates what emotions are deem

ed acceptable to express, and to what extent. Gross contends with Ord, writing, “All public expressions of grief act as a mirror in which private feelings are reflected,” (3). The intimate, individualized experience of grief grows increasingly complex as cultural forces alter the manifestation of the emotional experience.

The ambiguity and discursiveness surrounding grief makes for a daunting process, portraying isolation as the safest option. However, denial and isolation can be a self-deprecating space to dwell in, often prolonging and worsening the weight of loss.

New Orleans is no stranger to death. The city’s infrastructure, or lack thereof, has led to soaring death rates and detrimental tragedy throughout its history. A Community Health Improvement Report, provided by the New Orleans Health Department in 2013, writes “Louisiana is consistently placed near the bottom of national health rankings, currently 49th” (5). More specifically, this report demarcates Orleans Parish as having the poorest health outcomes, compared to neighboring metropolitan areas, with a high prevalence of obesity and diabetes, smoking, violent crime and childhood risk factors (5). Institutional instability has been a driving force in challenges to mitigate lethal circumstances, both controllable and uncontrollable. Essayist Nancy Gibbs once referred to this sacred city as a “sand castle set on a sponge nine feet below sea level,” explaining the city’s fragile standing and its vulnerability to effectively respond to uncontrollable circumstances, like Hurricane Katrina (2). Even with knowledge of this monstrous storm heading in the direction of the city’s coast two months prior, Ray Nagin, New Orleans’ mayor, announced an inability to provide citizens with transportation as a means to evacuate as they lacked the necessary funding. Once Katrina had swallowed the city, the local government then fired 3,000 municipal employees for the same reason (2). With little to no funding to properly deal with the scale of such profound tragedy and death, corpses accumulated in number on the streets, sitting untouched for nearly a week before they were removed (2). Growing increasingly unstable in the face of Katrina, the city was forced to further dismantle their public system, with school systems that were already ranked as the worst performing in the nation and some of the highest crime rates in the nation in 2005 (2).

One of many boarded-up buildings after Katrina hit.

For New Orleanians, such frequent tragedy presents itself as a vow to live, especially for those who are no longer able to. The spirit and soul of this eccentric city is founded on diversity, adopting cultural practices from all over the world. Famously known for jazz funerals and second-line processions, the city leans on rituals rooted in African and West Indian culture. Richard Brent, author of Jazz Religion, the Second Line, and Black New Orleans, delves into the city’s culmination of death-related practices, examining the rituals’ origins and their impact in modern-day society. Utilized by the African American community during enslavement, jazz music in burial rituals allowed for spiritual healing. Brent writes, “New Orleans jazz funerals synthesize spiritual and musical elements from Vodou, Christianity, and African American and Congo Square music to recreate, strengthen, and mend the relationships between the community of the living, the ancestors and the dead” (1). Dripping with sequins, flowers and fringe, second-line participants today use grief as an opportune time to dance in honor of the dead, moving, stomping and clamping, to celebrate rebirth and get lost in the rhythm of African diaspora (4). While New Orleans relies on jazz funerals and second-line processions in grieving, every culture has death-related ceremonies to acknowledge the life that has been lost and facilitate the continuation of normal life.

The soothing spirit of jazz has its limitations to healing, as guilth* lingers through the brain of grievers, preventing introspective thinking and reflection necessary to reach the fifth stage of grief, acceptance. Often prompted by the loss of a child, looming guilth positions self-inflicting shame as a barrier to making sense of what has occurred, ultimately preventing any progression in the grieving process. Gross explains, “Regardless of the age of the child, ‘to most people in the West, the death of a child is the most agonizing and distressing source of grief’” (3). The unexpected timing and notion that so much life was robbed, leaves those suffering to feel piercing sensations of responsibility. Specifically, Gross explains that individuals experiencing the sudden loss of an adult child has led to more intense, persistent grief and depression than the loss of a baby or young child (3). With this in mind, it becomes increasingly clear that leaning on a jazz-filled celebration for spiritual healing, while prevalent in its practice, does not fit the mold for everyone experiencing grief.

This challenge calls for a solution — one that values specific individual needs, while relishing the spirit of cultural practice. Ashé Cultural Arts Center, a New Orleans nonprofit organization founded on principles of cultural acceptance, utilizes art to support human and community development, through artistic expression that aims to preserve the contributions of African descent within the local culture. By combating secondary stressors, like social isolation, in the process of grieving, Ashé fosters an environment for creative expression through community engagement and group efforts. The individualized aspect of artistic production, within a larger context of group congregation, allows for a sense of belonging to reorient the individual suffering. Gross discusses the beneficial nature of mastering a skill and socially integrating oneself in easing the pain of grief, which is exactly what Ashé does in their work.

New Orleanians gathering to partake in traditional funeral processions with a second-line celebration.

Although Ashé Cultural Arts Center does not specifically target grieving individuals, it presents a viable option to escaping the weight death inflicts on individuals who have lost a loved one. It channels the powerful healing spirit of African culture through an avenue of self-expression and unity. To combat the perils of grief, knowledge of its multilayered existence is important; the psychological universality that prevails in the midst of its discursive functionality.

Processing death is difficult enough, and I can attest to the instinct to linger in denial and isolation. With denial and isolation marking a starting point and acceptance at the finish line, cultural practice is a medium to get from beginning to end. It is easy to get lost, or even stuck, in this process to get to the end, but we must lean on tools at our disposal to get there. In this journey to reach the finish line, comes a vastly different individual experience for everyone, but leaning on culture in a way that allows for personal freedoms and mobility makes the acceptance at the finish line seem a lot closer in its distance.

*Guilth (noun): the emotion experienced during grief that accounts for an inability to navigate individual introspective thought processes that allow for psychological peace as a result of guilt

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.