Imagine this: You have been in prison for years because you made a mistake in your life. You go to prison to repay your debt to society and to rehabilitate yourself, seeking to get better and hope to succeed for a new shot at life with a fresh start. After you do your time, you get released into the real world and hope to get back on your feet. You’ll look for a job to try to build up some of the income and savings you weren’t able to accumulate while you were behind bars.

Imagine this: You have been in prison for years because you made a mistake in your life. You go to prison to repay your debt to society and to rehabilitate yourself, seeking to get better and hope to succeed for a new shot at life with a fresh start. After you do your time, you get released into the real world and hope to get back on your feet. You’ll look for a job to try to build up some of the income and savings you weren’t able to accumulate while you were behind bars.

But it turns out that it’s not so easy to get a job as an ex-con. The harsh reality is that you will be looked at differently and likely will not be treated the same because people have the presumption that since you made that one mistake earlier in your life—even if it wasn’t violent or directly injured anyone—you cannot be a reliable employee. You have now been tossed into the real world without any form of safety net or backup plan and it will now be even harder to live then it was in prison because you need to pay for your own food, your own housing, and even your own medical care.

Now, think about this: The world is in the midst of a global pandemic, and, as a result, the economy is plummeting. Employees are getting laid off left and right and companies are going under. Even companies that are staying afloat are, often, instituting hiring freezes. It’s hard for anyone to get a new job right now, but especially so if they have recently been released from prison. However, job environments vary based on the state in which someone is looking for a job.

Take New York and Louisiana, for example. New York’s unemployment rate is 11 percent right now, but that number is likely to go down as it recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic in a much quicker fashion than states like Louisiana, which was late to enforce lockdowns, mask-wearing, and social distancing. Louisiana’s unemployment rate is closer to 15 percent right now, and it could go higher as it, and other Southern states suffer from increased COVID-19 case counts.

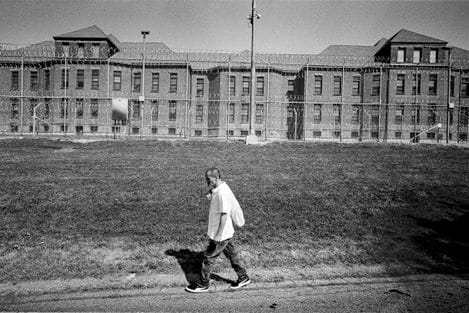

Those being released from prison don’t know exactly what they’re walking into. (Photo: Getty)

It’s important to note that those numbers are just for the general populations of those states because if you have been incarcerated before, your chances of getting a job are significantly smaller. This inequality is even more stark along racial lines, with minorities who have been in the prison system facing a steeper uphill climb toward finding a job. The unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated black women nationwide is around 44 percent and it’s around 35 percent for formerly incarcerated black men.

On the other hand, the unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated white women is around 23 percent and it’s around 18 percent for formerly incarcerated white men. The prevalence of race and its effect on employment numbers is a huge reason why states like Louisiana are at even more of a disadvantage, being a state with a higher minority group population compared to a state like New York.

Nearly 33 percent of Louisiana’s population is black compared to New York, where 16 percent of the population is black. Black people, especially, are disproportionately incarcerated and, as a result, suffer the harshest penalties in terms of post-incarceration employment searching. It’s hard enough to get a job during these times. Just imagine how hard it will be for people who just got out of prison.

This piece is part of an on-going series from professor Betsy Weiss’s class, “Punishment and Redemption,” which is taught at Tulane University. These pieces will be published every Thursday on vianolavie.org.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.