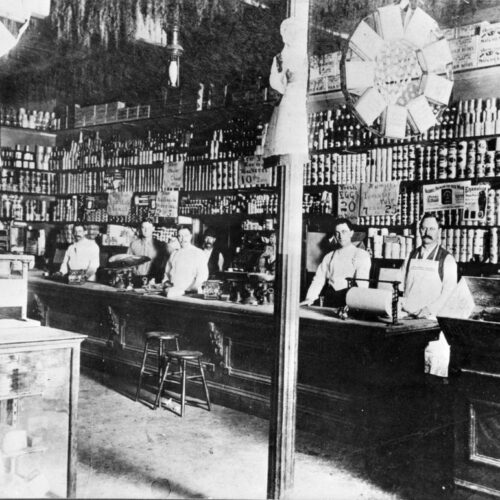

Photo taken of Schwegmann’s First Grocery Store, located on Piety and Burgundy St. in 1895 (The Times-Picayune archive).

A building that resided on the corner of Piety and Burgundy opened for business in 1869, unknowingly marking the blueprint for subsequent grocery stores. It had the classic New Orleans balcony style, with overhanging posts and green shutters. In the apartment just above this first self-serve corner grocery store, the Schwegmann family resided and ran their business. Flash forward to 1946, Schwegmann’s third-generation opened what would be the most recognizable Schwegmann Bros grocery experience. This massive white building with a three-arched roof became a hit for the locals; it had everything, including a bakery, shoe-shining station, jeweler, bank, and bar. The chain eventually expanded to include a massive store residing on St. Claude Avenue, establishing itself as the largest grocery store in the world, at that time. An enormous victory for such a small start, the Schwegmann’s franchise preserved a special place in its customers’ hearts over 50 years later.

I owe my knowledge of Schwegmann’s to my own family’s well-maintained attachment to its franchise. My grandparents, Paul and Gail Dillon, raised three children in Worcester, Massachusetts, but made the decision to follow work to New Orleans, Louisiana. My grandfather worked as a human resource supervisor at UPS after his service in Germany in the mid-1950s. After moving to Slidell, my grandparents already committed to buying a house, when my grandfather received a job demotion. The decrease in pay meant there was no way that my grandfather could support the house on one salary. My grandmother reentered the working field as a fourth-grade schoolteacher at Carolyn Park Elementary School. She expressed that “[going back into the work field] was very disappointing, I was not able to get more time with my children.” With three kids in Catholic school, two car notes, and a signed mortgage, they found it hard to make ends meet. “We ate lots of bolognas, tuna fish, and spaghetti,” my father recalls.

And suddenly, there was a shift in this dynamic. Schwegmann’s helped my family to be fed without going over budget while making the act of shopping an experience for everyone, children and adults alike. My grandparents would pack the whole family in their gold 1973 Oldsmobile station wagon and drive to Gentilly to shop at Schwegmann’s groceries. My father recalls walking into the store for the first time, “I must have been around eleven years old… it was so huge, like a superstore, three times the size of what I was used to.” He remembers his parents unlatching the trunk after the drive home to reveal the twenty-three grocery bags piled high and proud. This was the gift that Schwegmann’s gave my grandparents; it created an opportunity to provide for their kids in ways they would not have been able to otherwise.

All of this to say, nostalgia is a social experience that unites our individual perspectives together into this surreal retrospective time travel. When asking my father about a memory of Schwegmann’s, he immediately recalled, “They had popcorn kernels that were all different colors, red, green, blue… these are things you notice as a child.” The memories he still holds are reminiscent of the blissful naivety of childhood. Through tapping into this sense of nostalgia, he can explore the world through his own eyes before he discovered the realities of adulthood. Although my grandfather is no longer living on our same plane, my father can still connect with him through his memory. There are monumental moments and there are ordinary moments that fill Life’s cup to the brim, but both instances have the potential to stand out as precious after a life or an era has completed. This same logic can be applied to the absence of Schwegmann’s: the business still lives within the hearts of the community it served because the memories it created are still cherished.

Schwegmann’s Grocery Store at the Airline Hwy. location in 1954 (Photo via The Times-Picayune archive).

What did Schwegmann’s Supermarket do differently? To understand the impact of Schwegmann’s groceries, it is important to reexamine just how consumer loyalty affects business. According to studies, “emotion and consumer behavior outcomes are strongly linked.” Schwegmann’s provided its customers a social experience, deviating from the monotony of the normally mundane task of grocery shopping. The mere enormity of the buildings and aisles astounded anyone who walked inside. People in lower socioeconomic classes finally found a resource within their own community that worked with them rather than against them. This was the difference between Schwegmann’s and a megastore, like Walmart, Sam’s, or Costco: Schwegmann’s provided a greater intimacy and compassion to their customers, thus bloomed the public adoration for the Schwegmann experience.

So, with this mutual recognition between business and the audience it serves, customers became committed to its memory through positive emotional attachments. Positive memories impact the storage of information within our brains, “reception of stories can evoke a specific form of emotion: empathy.” Empathy helps a narrative keep moving while maintaining the audience’s interest, entertaining their pathos long enough to see a story’s ending through. In Schwegmann’s case, empathy was essential to its history. The nostalgic attachment the New Orleans community holds towards Schwegmann’s grocery store could not have been achieved without the role of compassion. Customers felt seen, appreciated, and valued within the Schwegmann doors. Although Schwegmann’s Supermarket franchise did not survive into the year 2000, its lasting impression is still prevalent today, both within my father’s memories and within the New Orleans community.

This piece was written as part of the “Archive Dive” series. It is produced for the Alternative Journalism class taught by Kelley Crawford at Tulane University.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.