By: Isabel Cutler

“Welcome to Beautiful Downtown Cancer Alley!” (Photo by: Daniel Ford)

In 1909, Standard Oil opened a refinery at the edge of Baton Rouge, Louisiana. At first, this was seen as an effort to improve the economies of surrounding low-income communities. However, the oil refineries poisoned the drinking water and clean air, causing significant harm to the residents. The Louisiana Office of Conservation reported that “thousands of oil waste pits, many leaching toxic chemicals, were scattered across Louisiana.” Natives slowly became aware of the groundwater contamination and noticed how disease spread along those who lived by the river. Due to these findings, citizens named the area “Cancer Alley.”

Cancer Alley is an area along the Mississippi between Baton Rouge and New Orleans in the river Parishes of Louisiana. The Louisiana Tumor Registry offers very little data that can be effectively tracked based on geography. Citizens feel they lack reliable data, so linking the disease patterns to pollution from Cancer Alley is nearly impossible. In court, many attorneys find it difficult or even impossible to get medical data that can prove the pollution’s effects on any given community. The citizens inhabiting this area have not been adequately supported by their officials and, therefore, cannot live healthy lives.

A young family with the last name Hebert lives in Destrehan, a parish right along Cancer Alley. Both parents work full-time jobs and can barely provide for their children. Because of their socioeconomic status, the family is exposed to environmental inequality, and their health is at risk. The quality of life in Louisiana has been previously rated nearly the lowest in the nation. Citizens who live within a mile of the factories in Destrehan are exposed to constant water and air pollution, odors, and loud noises. The roads are very narrow and unkept. Most of the communities along Cancer Alley are living in poverty. However, the taxation policies have also increased the level of industry in their neighborhood. “About a quarter of the nation’s petrochemical facilities are located there.” The oil industry on its own generates roughly $17 billion annually; still, that money is not used to help any of the local residents. With such a large profit margin, many residents feel the money should go towards fixing the roads or working to provide them with clean water.

While the chemicals negatively impact their family in several ways, the drinking water quality is the greatest concern for the parishes along Cancer Alley. The Hebert family has publicly complained that their water tastes and smells bad, and their kids are afraid to drink it. “The problems of the bayou stem from several sources including waste disposal from boats, chemical release from industry sources, and seepage of fertilizers and pesticides from agricultural production.” Algae blooms and covers the top of the bayou as a result of this, and the only way to clean the water after this is to use a very high level of chlorine. The Herbert family is often told to buy plastic single-use water bottles to avoid drinking the dirty water. However, the Herbert family is not financially equipped to purchase plastic water bottles constantly, and there is no way to recycle plastic in their neighborhood.

Many young families live in a nearby town called Plaquemine, where Dow Chemical Corporation’s largest petrochemical plant in the state is located. Dow buried tons of toxic waste in unlined pits covering acres of land. The company is trying to pump the waste and allow it to reach back to the surface before it damages the drinking water for the city. Until then, the Mississippi River rises and floods the waste site every time it rains. During rainstorms (which are common in New Orleans), toxins are carried into the river and poison the water supply as it travels further downstream. The children here walk to the bus stop every day with a stench of chemicals they cannot ignore. Before the pandemic, they were already wearing masks to walk to and from their bus to mask the scent of waste from the Dow Chemical Corporation.

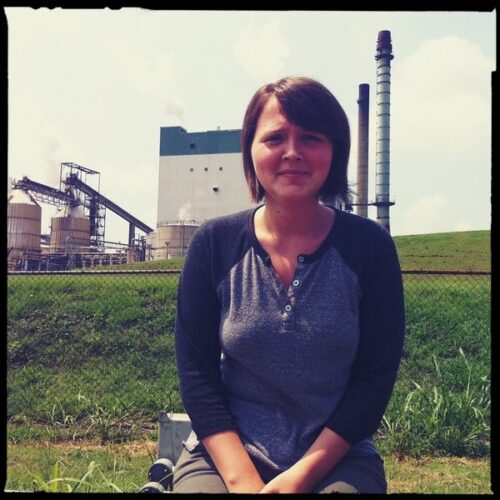

Factories in Cancer Alley

The oil refineries along the coast of the Mississippi River are putting people just like the Hebert family in economic and sociological jeopardy. Residents along Cancer Alley are concerned for their health and continue to live in dangerous conditions every day. Louisiana is ranked 47th in health in the United States. Citizens who get their drinking water from the Mississippi River “have as much as a 2.1 times greater chance of developing rectal cancer.” Additionally, the cancer rates in the entire state are highest downstream from the chemical corridor, which is certainly not a coincidence. Another study found that citizens who live within a mile of a chemical facility have 4.5 times greater odds of developing lung cancer. Thankfully, the Herbert family has yet to face the long-term repercussions of their environment. However, this does not mean that they are blind to what is happening around them and the effects that their neighbors who have lived there longer are facing now. As the Herberts fear the long-term health effects coming their way, they are dealing with skin inflammation, respiratory problems, and headaches. The Herberts are just one of many families inhabiting “Cancer Alley” who are not able to live safe and healthy lives due to the exploitation of their low-income town.

Works Cited:

BLUM, E. (2012). Cancer Alley (Louisiana). In THOMAS J. & WILSON C. (Eds.), The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Volume 22: Science and Medicine (pp. 182-183). University of North Carolina Press. Retrieved September 15, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9780807837436_thomas.45

MCDEARMAN, K. (2012). Barnard, Frederick A. P.: (1809–1889) EDUCATOR AND SCIENTIST. In THOMAS J. & WILSON C. (Eds.), The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Volume 22: Science and Medicine (pp. 181-182). University of North Carolina Press. Retrieved September 15, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9780807837436_thomas.44

MISRACH, R., & BERRY, J. (2001). CANCER ALLEY: THE POISONING OF THE AMERICAN SOUTH. Aperture, (162), 30-43. Retrieved September 15, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/24472700

Singer, M. (2011). Down Cancer Alley: The Lived Experience of Health and Environmental Suffering in Louisiana’s Chemical Corridor. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 25(2), 141-163. Retrieved September 15, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23012125

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.