As one of the oldest cities in the United States, surpassing its 300th birthday a few years ago, New Orleans has seen points of inspiration and influence come from everywhere in the world. Whether French, Vietnamese, or Spanish, there exists a tightly knit network of veins pumping spiced blood through every street and across every avenue; be it architecture, economic structure, or food. So naturally, as a city with so much cultural firepower, as well as being a notorious party destination, New Orleans has a well-known and bustling tourist industry. In fact, according to NewOrleans.com, tourism “contributes almost 43% of the city’s sales taxes.” However, the historic practice of visiting the Crescent City lends itself to another industry, one that’s been a part of the city since the beginning: hotels. However, with the need for tourist lodging comes the question of how beneficial this industry is for the people of New Orleans. I, for one, think it isn’t. Case in point: the St. Louis Hotel.

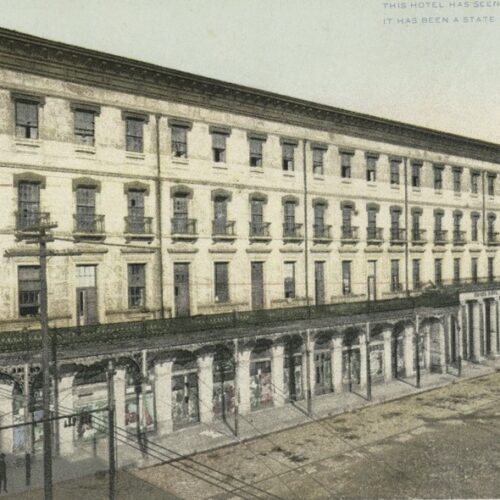

Originally breaking ground in 1838 and establishing itself as the “City Exchange” in 1843, the St. Louis Hotel served as a localized hotel giant rivaling those built by Anglo-American visitors to New Orleans, specifically The St. Charles Hotel in close vicinity to Canal Street.

“St. Louis Hotel: A Complex Tale of Creole Success and Complicity in Slavery’s Legacy”

At the turn of the 19th century, New Orleans was rapidly becoming “one of the nation’s most important ports,” and the constant visitation of sea-faring travelers led to the rise of tourism, with new travelers entering the city by sea every day. Quickly becoming a massive draw for tourists, and a site well-known for its extravagance and high-class balls, what made the St. Louis so important was its significance to Creole culture in New Orleans. The hotel was, after all, established by Creole residents to challenge Anglo-American domination over the hotel industry in the city. By definition, according to NewOrleans.com, “Creole” refers to someone “of mixed racial ancestry, with deep local roots, and family members who are Catholic…that is, Franco-African Americans.” However, what I think makes the Creole aspects of New Orleans culture so disheartening, and what argues against the economic benefit for all New Orleanians in the context of the St. Louis Hotel, is their connection to slavery. You see, while Creole people in 19th-century New Orleans were able to move about freely in society, “legally equivalent to whites,” their darker-skinned counterparts, brought over from Africa, were treated as many black men and women were at the time: as slaves.

Before the American adoption of Louisiana in 1803, Creole people were given significantly more opportunities than their enslaved brethren;, some Creole New Orleanians, most likely having roots of African descent, even owned slaves themselves. So how does this connect to the St. Louis Hotel? Well, St. Louis was the symbol of Creole success in New Orleans: the ability for individuals of mixed race ethnicity and foreign lineage to establish one of the most decadent and well-respected hotels and high-class party destinations in the city. Meanwhile, in the hotel’s rotunda, “the grandeur and spectacle” of slave auctions was witnessed and participated in daily. I mean, its original name, “The City Exchange,” practically lends itself to its true purpose as a gussied-up slave market. What this reveals to us is the pressure on Creole New Orleanians to reject their heritage and connection to other groups in favor of economic benefit. At a time when racial tension was running hotter and hotter by the day, and even in New Orleans, one of the more racially mixed cities in America at the time, people were still afraid to step out of line.

In the time surrounding the Civil War, the concepts of race in the U.S. began to intensify. With New Orleans serving as a unique and attention-grabbing port city in the very much slave-centric Louisiana, its existing identity as an observer of Code Noir logistics began to alter with the times. With New Orleans being a valuable port along the Gulf Coast, both the Union and Confederacy vied for its control. By 1862, New Orleans fell under the Union banner, and with its capture, the St. Louis was made into a hospital for wounded northern soldiers. It remained the epicenter for slave auctioning up until then. To some, the transformation of St. Louis from an opulent hotel to a temporary hospital diminished its grandeur. However, what I want to argue here is, that despite its grandiose architecture and rich history, there was nothing grand about it at all.

Masking itself as the pinnacle of progress in the antebellum South, St. Louis was merely the mask with which mixed-race individuals used to pass through life, free of controversy and without shame for their enabling of twisted tradition. However, is there room for improvement? Can we as a society acknowledge this seedy aspect of history and move forward?

By the end of the war, and with Reconstruction of the South well underway, St. Louis was established as Louisiana’s impromptu capital, before its eventual movement to Baton Rouge in 1882. The St. Louis once again returned to its purpose as a hotel. However, due to a lack of care during Reconstruction, the St. Louis couldn’t turn a profit, leading to its abandonment in 1912. Only three years later, The Great Storm of 1915 demolished it. What was once considered by many to be the pinnacle of Creole culture, serving as a beacon of Southern progress during Reconstruction, and acting as the home of Louisiana’s government for two decades, was now rubble and broken glass. However, with this destruction came the exorcism of hundreds of thousands of slave souls, auctioned off within its hallowed halls while the mixed-race Creole citizens hid behind their passing privileges and lived gloriously.

It took most of the 20th century before plans for a re-establishment of St. Louis came into place; until 1960, to be exact. Under new management in the form of Edgar and Edith Stern, things were beginning to look up for this crop of land. Edgar was, after all, the recipient of the Times-Picayune Loving Cup for his work establishing Dillard University and Flint-Goodridge Teaching Hospital for African Americans; not to mention his work toward voter registration reform in the Jim Crow South. The restoration/rebuilding project was handled by Samuel Wilson, Jr. Dubbed the “Dean of Historic Preservation,” Wilson spent much of his adult life rehabilitating hundreds of notable historic structures in Louisiana and Mississippi. After switching hands throughout the 1960s and 70s, the building, now named the Royal Orleans, ended up in the lap of Omni Hotels, rebranding it as the Omni New Orleans in 1986, becoming a joint property of Omni and local New Orleans investors. Still draped above the hotel’s Chartres Street entrance, the word “change” exists, a faded reminder of the building’s origins as the “St. Louis Hotel and Exchange.” Considering the property’s history, the word “change” seems almost ironic. But at risk of sounding cynical, has the Omni New Orleans brought any major change to New Orleans, or does the ghost of St. Louis still hang heavy in the air, with no Creole sin to atone?

I’m not stating that negligence toward race existed within the Creole people, but I think the Creole people were able to finesse the system established by white colonizers, at the cost of their disenfranchised Black cousins. The seemingly lax practices of Code Noir, and the ability of Creole people to pass as white, due to their mixed ancestry, allowed for a thinly veiled conception of racial lines along skin tone to root itself firmly in the economic structure of a relatively liberal city amid an economic boom.

The St. Louis Hotel, many years after its inception, is still a heated topic of debate for its place in New Orleans history, and more broadly, in the history of slavery in America. However, I think the worst thing we can do is ignore its implications in slavery and focus solely on its role in Creole power dynamics. Yes, The St. Louis Hotel was a major symbol of Creole success in the Antebellum South. But at what cost? When we situate St. Louis in this context and allow ourselves to look at it critically, we can attempt to unpack the progress made in the years since, rather than mask it as something it was not.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.