This article focuses on St. Charles Parish, which is only one of three parishes that make up the River Parishes/Cancer Alley. St. John the Baptist and St. James Parishes also face similar financial and health difficulties at the hands of oil refineries.

Part I: The Issue

St. Charles Parish is part of a collection of three parishes known as the river parishes. For the most part, people who grow up in St. Charles stay there, so there are generations of families within a few miles of each other. It is an incredibly small parish, 51,300 residents total, made up of stereotypical small southern towns where everybody knows everybody. The type of place where you have to watch what you say about someone, because odds are their friend or cousin is in earshot, and will undoubtedly report back. It is a small town of Church services, plant workers, and homecoming queens, where going to college is truly still an option. It is held together by families who refuse to leave, who have built homes on land saturated with oil pollutants, running tap water that is unsafe to drink.

Destrehan Plantation was built in the 1790s, located along River Road as an introduction to the River Parishes, a string of communities now commonly called Cancer Alley.

The river parishes have earned a new nickname in recent years: Cancer Alley. In 2014, the Environmental Protection Agency collected data for the National Air Toxics Assessments (NATA), and found that the national average for developing cancer from breathing air toxins was about thirty per one million people. However, in St. Charles Parish, the risk ranged from eighty to eight hundred per one million people.

In 1938, oil was found for the first time in Bayou Des Allemands, and thus St. Charles Parish grew from its status as the site of former sugarcane plantations into an oil refinery hub. Refineries began to settle on land formerly occupied by plantations, where “employee communities” were established in order to eliminate long work commutes. In the 1950s, workers moved into newly built subdivisions, and the community only continued to grow. Norco, a working class town in St. Charles Parish, earned its name as an abbreviation of New Orleans Refinery Company.

First built in 1980, Valero Refinery occupies 1,000 acres in Norco where it processes 340,000 of crude oil every day and employs over six hundred workers. It has recently planned for a $1.1 billion expansion that would make it the second biggest renewable diesel refinery in the world, producing 675 million gallons of renewable diesel every year for not only Louisiana, but Canada, Europe, and California. This expansion also includes $400 million allocated for the refinery’s alkylation unit, a refinery unit operation that adds high octane hydrocarbons to motor and aviation fuel.

Valero also produces soot outside of federal limits, the highest rates among all US refineries. Plants are required to restrict soot emissions to one pound or less for every 1,000 lbs of petcoke burned, but Valero’s average is between 1.02-1.04 lbs, peaking at 1.2 lbs. Soot is a form of particulate matter, which can bond with other toxins and infiltrate the bloodstream, causing damage to the cardiovascular system.

Shell Refinery is located behind a children’s playground in Norco. It employs about 1,200 parish residents, and is well known for the smell of rotten eggs, the signature scent of sulfur emissions. Additionally, it emits ethylene, propylene, butadiene, and aromatic feedstocks, all chemicals that have been linked to cancer development by the EPA.

St. Charles Parish also houses the top school district in the state. Ninety-five percent of residents attend public school, and the district boasts a graduation rate of 87.6% with an annual budget exceeding $202 million. It serves a student population with a 50% minority enrollment, where about 40% of all students are economically disadvantaged. It provides resources for its students and connects them to successful futures, an American luxury often afforded only to students from the upper middle class and beyond. However, due to regulations and high tax rates on oil refineries, the parish has the budget to fund student success. In 2019, Valero paid $15.4 million in parish property taxes and $11 million in sales tax. Shell paid $37 million in property taxes, which makes up about one-fifth of the parish’s property tax base. Both refineries also have philanthropic ventures in the community. In 2019 Valero’s donations in the community amounted to $2.25 million. In the wake of Hurricane Ida, Shell donated $5 million to community relief efforts.

Oil refineries expel chemicals that cause significant adverse health effects, many of them fatal, but shutting them down would decimate St. Charles Parish’s school budget and leave many residents without employment.

However, the oil industry has historically been unstable, and its future looks even more so. Shell has stated that it hit peak oil production in 2019. British Petroleum (BP) has sold one-third of its investment in natural gas production in order to raise funds to invest in renewable energy. However, these renewable energy efforts are currently operating at a loss, with many workers left unemployed, and the company doesn’t expect to see any profits until at least 2025. Governor John Bel Edwards concedes that Louisiana must also move towards renewable energy efforts; otherwise, the state’s financial future will be in ruin.

Part II: The Partial Solution

The oil industry’s attention is focused on climate change. Carbon Capture is a future many companies are looking toward, wherein oil production would continue, but it captures carbon dioxide emissions from sources like coal-fired power plants. Once it’s captured, it’s then compressed into a liquid state and transported by pipeline, ship, or road tanker and can be pumped underground into depleted oil and gas reservoirs.

Carbon capture focuses on its role in greenhouse gas emissions. While these are important, in parishes like St. Charles, environmental destruction goes beyond the sinking land and the changing temperature. It is damaging residents’ health, and carbon capture will not solve that public health crisis. Other sites of chemical destruction, such as the Love Canal, Valley of the Drums, and Times Beach, Missouri, are now ghost towns. Upriver in St. James Parish, the town of Reserve is known as “Cancer Town” and the parish itself is seen as a dying parish due to such high rates of cancer that has either killed residents or forced them to move. Gas stations, restaurants, a post office, and schools have left the parish. Reserve has fifty times the national average risk for cancer. Removing these oil refineries is not a viable solution, and using carbon capture will not negate negative health impacts. How can the river parishes fight against becoming ghost towns without sacrificing their livelihoods?

Part III: The Solution

On the border of Mississippi and Louisiana, in the small Concordia Parish, is a town called Vidalia. Sidney A. Murray, Jr served as mayor for six terms, beginning in 1960. In the 1970s, he devoted himself to reducing his constituents’ energy bills by utilizing the power of the Mississippi River instead of fossil fuel-generated electricity. Almost twenty years later, in 1990, his vision came to fruition, as the US Army Corps of Engineers built the largest prefabricated power plant in the world, the Sidney A. Murray, Jr. Hydroelectric Station, also known as LAHydro.

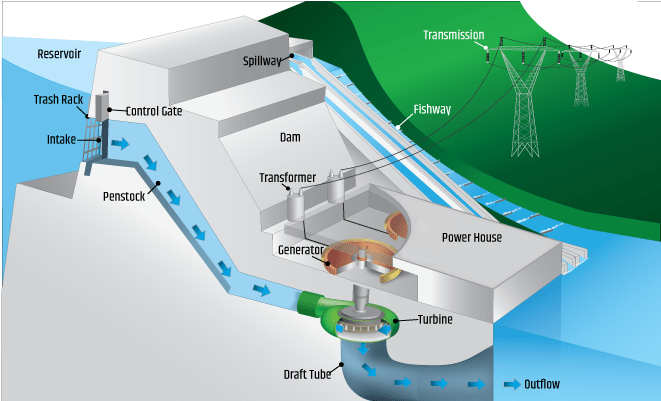

Hydroelectric power plants work similarly to coal-burning plants. In both, a power source turns a turbine, which then turns a metal shaft in the motor that produces electricity, the electric generator. A coal-fired plant uses steam produced from burning coal to turn the turbine, but hydroelectric plants use falling water. In Vidalia, the Mississippi River’s natural elevation drop provides the power to turn the turbine, utilizing water’s gravitational flow.

Depiction of how a hydroelectric power plant works

Hydroelectricity plants are created by first building a dam on a large river in order to store water in a reservoir. Near the bottom of the dam wall is the water intake, where gravity from the elevation drop will cause water to fall inside the dam through a gate called a penstock. At the end of the penstock is the aforementioned turbine propeller that is turned by the moving water. The turbine’s shaft goes up into the generator to produce power. Power lines are connected to a generator that carries electricity. In Vidalia, these power lines run to homes, providing fossil fuel-free and cost effective power. But, the reservoir in the dam can act like a battery, which will store power in the form of water if demands are low.

Hydroelectricity is the only renewable energy source that can replace fossil fuel production while satisfying growing energy needs.

However, hydroelectric plants are not suitable for all environments, as they rely on a river’s natural flow for power. Additionally, too many hydroelectric plants along a river can disrupt its flow, which would negate the purpose of the plants. It can also disrupt natural marine life; specifically, it can prevent fish from reaching their breeding ground, which can also negatively impact any animals that rely on that fish for food.

It is difficult to generalize the cost of building a hydro plant because each environment and river system can vary greatly. In Vidalia, it cost about $550 million from private investors to build the plant, but based on the Producer Price Index (PPI) inflation rates, that would be about $1.4 billion in 2021. Temporary job loss for coal-burning plant workers would also harm the community, but it would create temporary employment for nearby construction workers in order to build the hydroelectric plants. Furthermore, it would provide long-term, stable employment for the community in the face of a declining oil industry. Even more importantly, there is no financial cost that would outweigh the cost of residents’ lives.

Hydroelectric plants are not globalized like coal-burning plants are. Valero and Shell refineries produce oil not just for St. Charles Parish residents, but for companies and individuals across the world. Hydroelectric plants, as they have been currently implemented, can only provide power to neighboring regions because it relies on a system of underground transport lines, so they are therefore less profitable. However, considering the city of New Orleans proximity, St. Charles Parish could generate hydroelectric power not just for the river parishes, but for surrounding parishes, including Orleans, which would not only economically benefit St. Charles, but would lead to a significant reduction in energy costs for New Orleanians.

St. Charles Parish School District offices are located in Luling. They consistently rank highly in the state for education quality.

The school district, however, would likely face financial difficulties if the refineries were to close. While its budget doesn’t solely rely on them, the taxes the refineries pay are still a significant source of funding. Therefore, if the refineries were to transform into hydroelectric plants, the parish government would likely have to redirect budget spending to the school district, or else it would face large budget cuts. One such solution would be to gradually increase taxing on the refineries in order to create a significant base for education funding as the parish transitioned to renewable energy, but this is not an adequate long-term solution, as the money would eventually run out. Another potential solution could be found in taxing residents outside of St. Charles Parish utilizing hydroelectric power, and utilizing those taxes to fund their education system.

This change would be financially significant from beginning to end. Valero and Shell refineries look to St. Charles Parish as major producers, and the oil companies are supported by residents and politicians alike. Either the companies themselves would turn their refineries into hydroelectric plants, or the refineries would close and the parish government would have to transform them. In Vidalia, the US Army Corps of Engineers built their hydroelectric plant, but St. Charles Parish may have to outsource that labor. There would be financial losses from this transformation as well, but without this, oil refineries will continue to pollute their air and water with carcinogens, and the parish’s future looks much like other US chemical wastelands. Furthermore, as climate change progresses, the oil industry as it currently operates will only continue to decline, which means these refineries, and, in turn, the parish, still face a financially uncertain future. Investing in renewable energy will dramatically change the parish’s future, as it is a look towards clean air and water, a life without as fatal health problems, and better financial stability.

This piece was written as part of Professor Kelley Crawford’s Alternative Journalism course at Tulane University.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.