Theresa Chatterton, 59, explains the rise in housing prices over the past 25 years and its impact on pricing out local residents. (Pedro Ortiz for VNV)

Bywater neighborhood is known as “one of the first areas to witness gentrification,” in New Orleans, and as that gentrification continues to grow, Bywater residents like Theresa Chatterton are suffering the consequences. Chatterton, 58, who has been a resident of Bywater for 25 years, has worked at the neighborhood institution, Frady’s. As a longtime resident, she provided insight into the community’s past, saying, “Everyone used to know everybody; everyone would say hello to everybody; everyone would watch out for everybody; everyone would sit together and talk whether you were the guy who cleaned bathrooms or the CEO of a bank. Everyone was equal in this neighborhood. Now, I see a bit of classism developing. The service industry that’s still here, we’re all still very tight, we’re very family-like, but the other people now have their own agendas, which don’t involve the rest of us.”

She elaborated on significant changes within the community that have emerged since 2005 — the year that the flooding due to non-properly managed levees inflicted significant damage on homes in the neighborhood and various establishments, and it also impacted the livelihoods of its residents.

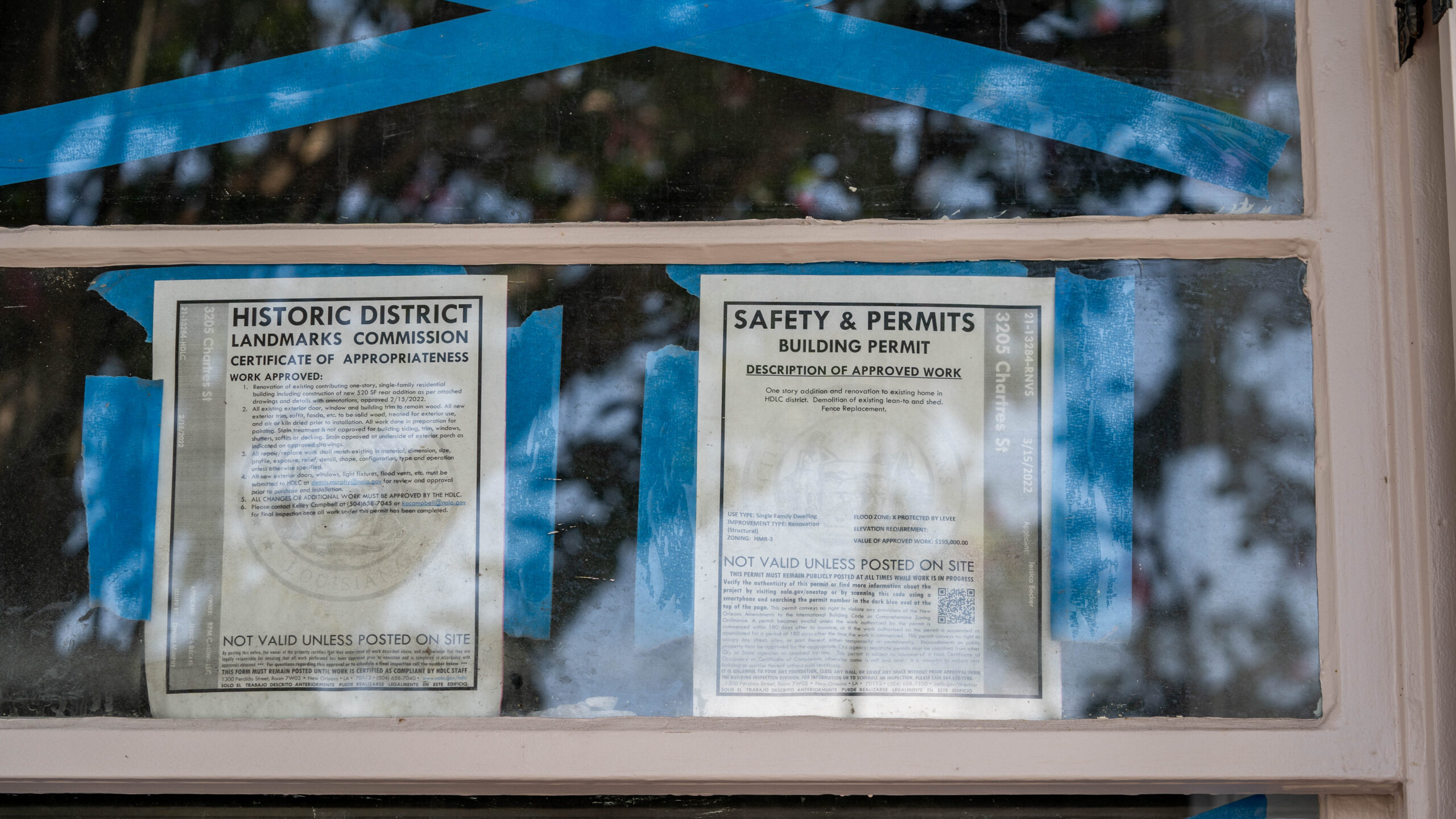

A building under renovation displays building permits in its windows in the Bywater neighborhood of New Orleans, LA, on Thursday, July 27, 2023. (Pedro Ortiz for VNV)

The reconstruction of the Bywater community has significantly altered the area’s demographics, as low-income and black residents have been forced to seek affordable housing in other parts of New Orleans and across the country. This shift occurred due to the scarcity of accessible housing following Hurricane Katrina and the neglect of the original residents’ needs. Instead of rebuilding affordable housing, out-of-state developers invested in the area, leading to a substantial increase in gentrification, tourism, and changes to the neighborhood’s perceived “quality.” Rent prices began to soar, and longtime tenants were priced out of their homes due to increased mortgages, rent, and property taxes.

A 30-year resident of New Orleans commented on the escalation in housing costs, revealing that homes in the Bywater district, once priced between $100,000 and $200,000, are now considered “reasonably” priced at around $500,000 to $600,000.

As the original community members are displaced, newcomers are contributing to the erosion of the area’s rich cultural heritage. Former family homes have been transformed into Airbnb rentals for a revolving door of tourists, and the once tightly-knit community has been forever altered. The culture that once thrived in the Bywater is becoming increasingly elusive. Theresa affirmed this sentiment, saying, “The sense of community is also not as strong as it once was because now the houses seem so disposable.”

26-year-old Demire discusses the neglect of black communities by local authorities in New Orleans, LA (Pedro Ortiz for VNV)

An article published in 2013 by Nola.com concerning the Bywater population from 2000 to 2010 confirms that “the percentage of the African-American population dropped by roughly 50 percent, from 6,786 to 3,333, while the white population grew by a little more than 20 percent, from 1,867 to 2,252.” When questioned about how federal and local authorities’ neglect of black communities has affected black residents’ housing situations, Demire, a 26-year-old New Orleans native, replied, “It’s felt in every way possible. It’s really in the fabric of the quality of living and in how the city is divided in terms of what gets funded and what doesn’t, what gets maintained and what doesn’t, and who invests in what, and what doesn’t get invested in. You just blatantly see it in the quality of the experience that people have here, depending on where their dwelling is.”

The housing situation of these low-income black residents heavily affects opportunities and basic well-being. The intentional relocation of these communities echoes the redlining that began in the 1960s, targeting black communities, a practice that, while thought to be a thing of the past, still affects the daily lives of low-income New Orleans residents.

Strong stereotypes regarding low-income communities often downplay the severity of the housing crisis. A 30-year resident revealed that he initially believed people in New Orleans were unemployed, but later realized the numerous jobs people must hold to survive, explaining, “You have to think about what you’re putting in your stomach first before you can consider other things like healthcare.”

Rachael, a 34-year-old who has resided in New Orleans for 6 years, expressed shock at the rise in rent prices, stating, “People are renting out parts of their garages without full kitchens and bathrooms for thousands of dollars, and the sad part is, people are willing to pay those prices.”

Ashley, 25, originally from Houston, TX, discusses the impacts of gentrification on historically black neighborhoods. (Pedro Ortiz for VNV)

Families that have resided in New Orleans for generations are finding themselves displaced due to the tourist trade aimed at infusing money into the city. Neighborhoods are being rebranded, homes are being renovated, and local citizens are pushed to the fringes. New Orleans homeowners and workers, essential in generating revenue for the city and its tourism industry, are often overlooked. Demire commented on the substantial revenue Louisiana generates, expressing concern over the lack of reinvestment in the community. Much of the money, instead of supporting the local populace, is diverted to the removal of low-income housing and the renovation of homes to render the city more “attractive.”

Matt Sakakeeny, a producer and professor at Tulane University in New Orleans, coined the term “culture bearers” for local musicians. As living costs in the city continue to climb, these “culture bearers” find it increasingly challenging to sustain their way of life. Sakakeeny highlights the post-Katrina period when musicians, vital to the economy, were forced to move back into the city. Yet, paradoxically, they were among those who received the least assistance from FEMA’s Disaster Relief Fund.

Jehan, a 61-year-old New Orleans resident who has been drawn to the city’s culture and community since childhood, offered her observations on the cultural shifts she’s witnessed over the years. Reflecting on her trips to New Orleans, she said, “As a kid, I didn’t know enough about what music was or should have been. I just remember there was jazz. I do know things changed during the years that I visited as an adult, and Bourbon Street changed. Bourbon Street went from traditional jazz to what it is now: often middle-aged white men playing rock and roll.”

Melani, a young resident of New Orleans discussess changes to her community. (Pedro Ortiz for VNV)

Some citizens maintain hope for the preservation of culture and livelihood in New Orleans, including the Bywater neighborhood. Melani, a young lifelong resident of New Orleans, expresses her optimism, saying, “I think the culture is still the same, and it’s still alive, no matter who lives where.” Despite the shifts in demographics, many residents believe the unique culture of New Orleans will continue to thrive.

As a community, recognizing those who have shaped New Orleans into the vibrant city it is today is vital. It’s essential to afford them the respect they deserve. When visiting, take the time to acknowledge and appreciate the people who laid the foundation for this dynamic metropolis.

A man discusses changes to the Bywater since he’s lived there. (Pedro Ortiz for VNV)

*This article was produced by students participating in the class “Picturing Social Justice in Housing,” as part of Tulane’s Pre-College program.

Contributors:

Hannah Alexander

Danielle Apfelbaum

Link Hammond

Dajrion Mccovins

Javier Ortiz

Liliana Poast Soler

Aima Shahid

Finn Zalanskas

Zee Bates

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

[…] program, students participating in the class “Picturing Social Justice in Housing,” focused on gentrification and its impact in the Bywater neighborhood of New Orleans. To investigate and ensure grassroots approaches, students talked to […]