Bettye Anding (Photo: Jason Kruppa)

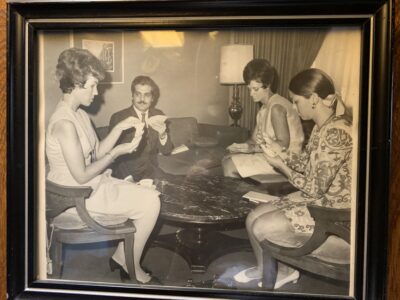

Several years ago, in an interview for ViaNolaVie, former Times-Picayune features editor Bettye Anding rolled out a wide-ranging array of war stories: arguments with astronauts and a brush with Elvis, card games with Omar Sharif and words exchanged with Mahalia Jackson, jocular sexual innuendo in the pre-#metoo era and, once, a bizarre interview with a guy in an iron lung. Student interviewer Mia Royce summed it all up succinctly: “That,” she said, “sounds badass.”

Badass indeed.

Bettye Tucker Anding, who died on Aug. 15 at age 88, was never one to do things by the book. From the very start, she defied convention, starting with that commonly held but uncommonly spelled first name.

“I guess that 20 percent of the girls living in my freshman dormitory in college were Bettys,’ she once mused in the Silver Threads column she wrote after retirement. “If you yelled “Betty!” you drew a crowd, so I was ‘Tucker’ to almost everybody pretty early on.”

She was named after her grandmother, but “of course, there was no final ‘e’ in Mammaw’s version of the name, and since my full moniker is Bettye Ann, I’ve often wished she’d just put that ‘e’ behind the two ‘nn’s in her afterthought. I’ve spent many, many years spelling that weird ‘Bettye’ for people who need to know it for one reason or another.”

Bettye-with-an-e would go on to explore that dichotomy between the expected and the unexpected in a long career as a ground-breaking journalist. Give her the everyday, the common thread running through people’s water-cooler conversation, and she would make it into something unique, something at once captivating and meaningful. In her 29 years as editor of the feature sections at the New Orleans States-Item and, later, The Times-Picayune, she worked that alchemy time and again. She wrote and oversaw stories that put everyday faces and accessible dialogue to important themes having to do with community, politics, gender, lifestyle, race, sexual orientation, culture and all the other myriad facets of life in New Orleans.

Bettye took the helm of the States-Item “women’s section” in 1971, a few years before I joined her staff as a very junior reporter. Before I arrived on her doorstep, she had already wrestled the lightly-dismissed Women’s Section into the more broadly appealing Family Section. She had campaigned successfully to abolish “women’s pay” – something that still ticked her off decades later.

Bettye Anding playing Bridge with Omar Sharif (Photo by Mia Royce)

“When ‘equal pay for equal work’ became the mantra of so-called ‘women’s libbers’ back in the ‘60s, some privileged dowagers got publicly worried about whether the small courtesies between the genders would be lost,” she wrote. “Me, I never worried about any of that — it was always about the money. And wounded pride — knowing that my paycheck contained only half of what the most inept of my male counterparts were receiving. Couple that feeling with those of working women whose wages meant sheer survival, and it isn’t any wonder that many of us saluted the bra burners.”

But Bettye was never an in-your-face activist.

“I will be so damn glad,” she once told me, “when we can quit writing the ‘first’ stories – the first firewoman, the first policewoman, the first woman executive. I can’t wait for that to not be news anymore.”

In her ability to both toe and cross the line, Bettye advocated women’s rights from the midst of the good-old-boy network of domineering white males who ran newspapering in those days. Bettye managed to fit right in with the testosterone crowd; she toed open the door, maneuvered her way in, and was respected for it.

As an editor, Bettye was demanding, smart, discerning and creative. She managed some 30 reporters, edited seven sections a week, wrote headlines, paginated pages and brainstormed story ideas. She knew innately what made a good lede, where the story should take you, and what was missing – if you were too lazy to get the quote, she’d send you back out. And while some judged her a hard editor by those standards, others knew that she always gave you that day off for a family event, or let you set your work hours so that you could get to school pickups. She was generous with her time and her counsel.

Bettye Anding and Paul Newman (Photo by Nora Daniels)

I have firsthand experience of that. Bettye was my mentor at both newspapers for 23 years. She was coach and cheerleader. I remember when, at 23, nervously turning in my first interview, she gave it a quick read and pronounced judgment.

“You don’t quote enough,” she said, pointing out where, in my story, I should have allowed my subject to tell the tale. I never forgot that first lesson, and still lecture student journalists on Bettye’s pointers for when to use expository writing and when only direct quotes will do.

Bettye was a fierce protector of her area of journalism. Features often get a bad rap, and she was never one to take it. When a surly city editor once informed her that the Living Section was only popular because it contained the comics, she didn’t argue; instead, she went to the national Belden survey to collect data showing that her feature section, in New Orleans, was second in popularity (and narrowly) only to sports – and ahead of the news section in readership. Even when the comics appeared elsewhere.

She kept her section current, too. Bettye knew when her audience wanted coverage of some newly popular topic, and debuted sections early on addressing parenting, say, or technology.

In many ways, the newspaper was Bettye’s family – she socialized with her colleagues, and threw many a party on her back porch with Bobby, her husband of 56 years. “Come on over,” she’d tell all and sundry. “Bobby’s going to make gumbo.” Bettye never did really cook.

She doted on her own kids, son Mark, who died in 1998, and daughter Jill, a fellow writer who remained her best friend and caretaker until Bettye’s death last week. Another real joy arrived with her two grandsons, Roke and Jack.

“She defined my life,” Jill said of her larger-than-life mother. Jill grew up in the newsroom, cavorting around the linotype machines under her mother’s eye, and listened to her stories for a lifetime. The silence now, she says, is a shock.

Bettye and Heidi (Photo courtesy Bettye Anding)

Bettye’s keen curiosity carried over into her private life. An inveterate traveler, she circled the globe over the years, often traveling with a group of newspaper food editors under the leadership of Eleanor Ostman, formerly of the St. Paul Pioneer Press. They were among the first to venture into a newly-reopened China in the ‘90s; they sailed the Nile. When Bobby bought an RV later in life, dubbed the Green Hornet, Bettye rode shotgun with him across the U.S.

Nor did she give up writing in her retirement. She started Silver Threads, a column devoted to seniors – another audience she felt under-represented – in her final years at The Times-Picayune, and continued it for almost two decades afterward at ViaNolaVie.org. In it, she weighed in on topics big and small: from whether or not she was still the alpha in her dog Heidi’s life (she had a lifelong predilection for dachshunds) to why people choose to live in New Orleans (as one woman once told her, “you can dance in the streets here when you’re 90 and nobody cares.”) She reflected on everything from Twitter (dismissing most users as “twits”) to driverless cars (what happens when you want to make a spontaneous U-turn into Appleby’s?). She wrote columns about TV binging and virtual reality and sexting. She compared Prohibition and new pot laws, and real books to e-readers. She penned all of it with a trademark turn of phrase and wit.

She also lamented the demise of legacy journalism, while detailing her own part in changing it. And she pondered the impact of female reporting, writing and editing across the years.

“One time my mother said to me, ‘Bettye, do you have any men working for you?’ And I said, ‘Yes.’ And she said, ‘Gasp, Bettye’s got men working for her!’ ”

Bettye-with-an-e. Badass, indeed.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.