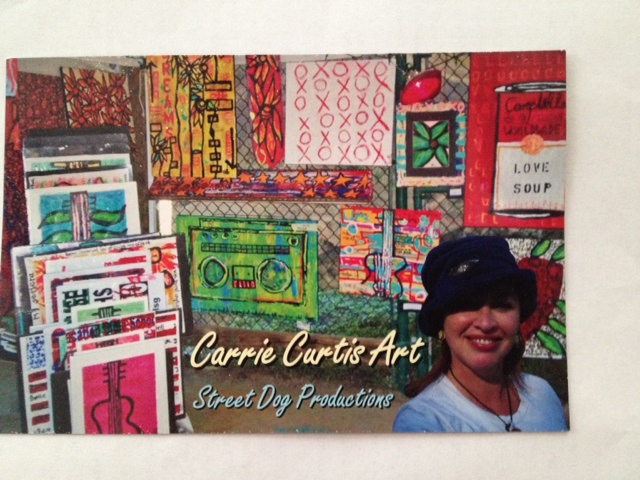

Permission to use this photograph given by Carrie Curtis; original photograph taken by Street Dog Productions

Carrie Curtis, a visual folk artist, smiles warmly to all of the people passing through Pirates Alley. The weather is chilly and damp. Even though the number of tourists in Jackson Square is less than what it usually is on St. Patrick’s Day, Carrie continues to slowly pace back and forth in front of her artwork, looking around with an expression of pure joy on her face. She has been selling her artwork on Pirates Alley, a road that runs perpendicular to Jackson Square, since she moved to New Orleans a year and a half ago from Opalaca, Florida. After visiting a few times, she decided that moving here would be the next step in her life. “Say yes to everything,” she told me. “You can’t let people tell you that you can’t do something. I’m supposed to be here. It isn’t easy doing this, but you have to be self-motivated. Carl’s over there painting even though his fingers are freezing. You gotta do it.”

Carrie arrives at Pirates Alley at 5:00 a.m. to claim her spot for the day. City Hall distributes more occupational licenses than there are available spots to occupy in and around Jackson Square, creating intense competition among the artists for the first-come-first-serve spaces in Pirate’s Alley. Her license permits her to tack her artwork onto two panels of the fence. After she hangs her paintings, she goes until 6 p.m. without a break. Taking a break, even to go to the bathroom, can be difficult and risky: “who watches your work while you’re breaking? Tough call there. Who is selling it? What if you are the only one out?” In her field of work, breaks are not always guaranteed. Sitting on a chair next to her art supplies is an opened purse containing a large, empty bag of potato chips. She resorts to bringing food with her in order to avoid leaving work. Although Carrie believes that working as an artist around Jackson Square is a challenging time commitment, she also believes that it is worthwhile. “Anything you want in life that’s important to you—you have to make sacrifices. In this town, she loves you, but she gonna show you some trying situations. You’re going to have to make some sacrifices,” she explains.

Pirate’s Alley is a small road where there are fewer tourists, artists, and less noise. Carrie likes to work in Pirate’s Alley because the artists are all friends who support and look out for one another. This is a warmer refuge from Jackson Square, where Carrie felt rejected upon her arrival. She tears up and her voice breaks, as she explains that a sense of community is lacking among the artists there because the majority of them are interested in selling their work rather than befriending and helping other artists. That day, the artists on the other sides of the Square do not appear to interact with each other, except for a couple of artists, who sell their work together. When they do not show and describe their artwork to prospective customers, they keep to themselves and their creations. On the other hand, the artists who work alongside Carrie seem friendly. They smile at us as they listen to our conversation. “We all get along really well,” Carrie says.

In addition to being an artist, Carrie works as a banquet bartender, server, and on-call captain at Hotel Pavillon and also as a bartender and waitress at Café Soule. After 11-hour plus days on Pirate’s Alley, she works eight to ten hour shifts for the other two jobs. Her schedules at the hotel and café change every week; her schedule as an artist is not fixed, making her typical for a creative worker. She is more comfortable with this temporal structure in her job. She is also happy that her home in the French Quarter is close to work. Her location, however, is disruptive to her sleep: “sleep? What’s that? I live between Bourbon and Royal. Last night I heard a woman getting beat up on my street at 3:30 a.m. Life in the Quarter ain’t no joke. It’s real.”

Carrie’s experience as an artist in New Orleans has been less complicated than her previous one in Florida. While living in Orlando, she owned an art gallery and started “Live Art Free,” an event to which she invited artists throughout Florida to come to Orlando to show their work for free and without needing occupational licenses—permits that allow them to occupy a certain part of a street. For Carrie, “Live Art Free” was very stressful because she had to manage the publicity and hire the artists and the bands by herself. She had to deal with 30 artists all at once; now that she focuses solely on selling her artwork around Jackson Square, her job is simpler. Also, today’s forms of social media, like Facebook, facilitate advertising her artwork to the public because they allow her to do so for free. Carrie says that Facebook is good for “anybody that is trying to keep folks informed on what they are up to. It keeps the customers together as well. Folks that bought from me are likely to have a common ground of some kind. Facebook [gives] anyone that is new to New Orleans, [or] maybe just visiting, a chance to see the work that I post daily—[to] see what local artists are doing. Before Facebook[,] sharing information [was] [by] word of mouth.”

As Carrie starts to pack her artwork up, a tourist comes by, showing interest in her pieces. Despite the fact that Carrie has been standing out in the cold all day, as well as the fact that she appears ready to go home, she enthusiastically greets the tourist and even offers to lower the price of her artwork without being asked. At the end of our conversation, she reminds me that her job “is work. [You] have to be motivated and maintain a positive image. [You] have to be a good representative of Orleans Parish[,] so that [tourists] come back, and go home with great memories from New Orleans and [a] friendly nice image of people there” (Carrie Curtis interviewed by Zane Wilson. Jackson Square. March 17, 2014).

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.