The following article is from the literary news site, Press Street: Room 220. The original article can be found here.

Room 220‘s unfortunately infrequent series of excerpts from literary works whose subjects pass through New Orleans continues with an excerpt of an interview and a passage from a novel by American literary giant Don DeLillo. Previous “New Orleans in Passing” entries featured excerpts from Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy and Naked Lunch by William S. Burroughs.

The new issue of the New Orleans Review includes an interview with Don DeLillo by Kevin Rabalais. Read an excerpt of the interview with DeLillo below in which he describes conducting research for his novel Libra, a fictional imagining of the early life of Lee Harvey Oswald leading up to the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Oswald was born in New Orleans and lived here on and off throughout his life. After the interview, we’ve included a brief excerpt from Libra that depicts Oswald as a student in the city.

From “A Man in a Room: An Interview with Don DeLillo”:

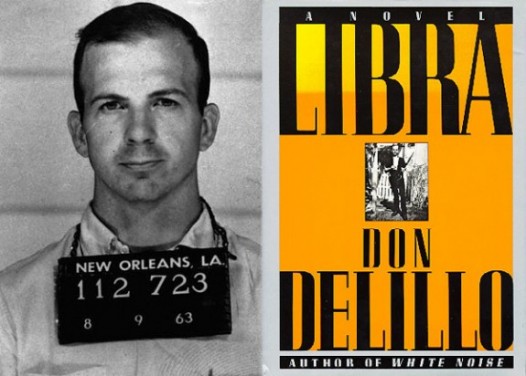

Lee Harvey Oswald’s mug shot, following an arrest for unlawful agitation and distribution of pro-Castro literature, in New Orleans on August 9, 1963, along with the cover from the first edition of Libra.

New Orleans Review: Is there anything typical about the way a novel begins for you?

Don Delillo: It’s not always the case, but it’s fairly frequent that the books begin with images. In Point Omega, the image was Norman Bates and his co-actors in Psycho. I make random notes for a time before starting, not necessarily for a long time. I have no structure, no sense of outline. I never do an outline. I scribble possible names for characters as characters slowly enter my mind. It’s almost casual. And at some point, I feel ready to sit down and start writing.

NOR: Would Libra—a novel in which you were dealing with a historical subject and real figures—be an exception to that?

DD: With Libra, I had an arc. What happened with Libra was the enormous amount of material that accompanied the assassination itself, like the Warren Report, which I didn’t feel I had to master, but nevertheless it was very helpful in a number of ways. But a sense of structure took a while to develop even with Libra, an idea that there were two parallel streams, one involving the life of Lee Oswald, the other involving the plot to assassinate the president. These are alternating chapters up to a certain point, and then the two ideas join when one of the characters, David Ferry, tells Oswald that you have to come with us and join our plan, our plot, and then there’s just one stream after that. That was the structure, and it took a while to develop in my mind.

NOR: You did extensive research for Libra, not only reading but also traveling to some of the locations that you feature in the novel. You also went to the desert to research Point Omega. Do you need to see the places that you write about?

DD: For Libra, I went to New Orleans and to Dallas and Fort Worth, and even Miami to see Little Havana. Do I need to travel? There are times when I haven’t. There’s a Beirut chapter in Mao II, and I couldn’t get there because of the war. In other situations, I haven’t needed to, or I simply didn’t think it was that necessary.

NOR: What kind of research do you do when you’re on these trips?

DD: I will always have a pencil and paper, simple as that. Back in the hotel room, I’ll take notes. Or I may write as I’m standing in the street. I remember being on Magazine Street in New Orleans and looking at the house where Oswald and Marina lived for a time, and being very touched, somehow, by just the sight of it, an almost over-pretty house. They were boarders, and at the time they couldn’t afford a garbage can, so he used to sneak the garbage out and put it in neighbors’ cans.

++++

From Libra:

A classmate, Robert Sproul, watched him cross the street. He carried his books over his shoulder, tied together in a green web belt with brass buckle. U.S. Marines. His shirt was torn along a seam. There was smeared blood at the corner of his mouth, a grassy bruise on his cheek. He came through traffic and walked right past Robert, who hurried alongside, looking steadily at Lee to draw a comment.

They walked along North Rampart, on the edge of the Quarter, where a few iron-balconided homes still stood among the sheet-metal works and parking lots.

“Aren’t you going to tell me what happened?”

“I don’t know. What happened?”

“You’re bleeding from the mouth is all.”

“They didn’t hurt me.”

“Oh defiance. You’re my hero, Lee.”

“Keep walking.”

“They made you bleed. It looks like they rubbed your face in it all right.”

“They think I talk funny.”

“They roughed you up because you talk funny? What’s funny about the way you talk?”

“They think I talk like a Yankee.”

He seemed to be grinning. It was just like Lee to grin when it made no sense, assuming it was a grin and not some squint-eyed tic or something. You couldn’t always tell with him.

“We’ll go to my house,” Robert said. “We have eleven kinds of antiseptics.”

Robert Sproul at fifteen resembled a miniature college sophomore. White bucks, chinos, a button-down shirt open at the collar. This was the second time he’d encountered Lee in the streets after he’d been knocked around by someone. Some boys had given him a pounding down by the ferry terminal after he’d ridden in the back of a bus with the Negroes. Whether out of ignorance or principle, Lee refused to say. This was also like him, to be a misplaced martyr and let you think he was just a fool, or exactly the reverse, as long as he knew the truth and you didn’t.

It occurred to Robert that there was, as a matter of fact, a trace of Northern squawk in Lee’s speech, although you could hardly blame him for it, knowing what you knew of his mixed history.

++

He spent serious time at the library. First he used the branch across the street from Warren Easton High School. It was a two-story building with a library for the blind downstairs, the regular room above. He sat cross-legged on the floor scanning titles for hours. He wanted books more advanced than the school texts, books that put him at a distance from his classmates, closed the world around him. They had their civics and home economics. He wanted subjects and ideas of historic scope, ideas that touched his life, his true life, the whirl of time inside him. He’d read pamphlets, he’d seen photographs in Life. Men in caps and worm jackets. Thick-bodied women with scarves on their heads. People of Russia, the other world, the secret that covers one-sixth of the land surface of the earth.

The branch was small and he began to use the main library at Lee Circle. Corinthian columns, tall arched windows, a rank of four librarians at the desk on the right as you enter. He sat in the semicircular reading room. All kinds of people here, different classes and manners and ways of reading. Old men with their faces in the page, half asleep, here to escape whatever is out there. Old men crossing the room, men with bread crumbs in their pockets, foreigners, hobbling.

He found names in the catalogue that made him pause with a strange contained excitement. Names that were like whispers he’d been hearing for years, men of history and revolution. He found the books they wrote and the books written about them. Books wearing away at the edges. Books whose titles had disappeared from the spines, faded into time. Here was Das Kapital, three volumes with buckled spines and discolored pages, with underlinings, weird notes in an obsessive hand. He found mathematical formulas, sweeping theories of capital and labor. He found The Communist Manifesto. It was here in German and in English. Marx and Engels. The workers, the class struggle, the exploitation of wage labor. Here were biographies and thick histories. He learned that Trotsky had once lived, in exile, in a working-class area of the Bronx not far from the places Lee had lived with his mother.

Trotsky in the Bronx. But Trotsky was not his real name. Lenin’s name was not really Lenin. Stalin’s name was Dzhugashvili. Historic names, pen names, names of war, party names, revolutionary names. These were men who lived in isolation for long periods, lived close to death through long winters in exile or prison, feeling history in the room, waiting for the moment when it would surge through the walls, taking them with it. History was a force to these men, a presence in the room. They felt it and waited.

The books were struggles. He had to fight to make some elementary sense of what he read. But the books had come out of struggle. They had been struggles to write, struggles to live. It seemed fitting to Lee that the texts were often masses of dense theory, unyielding. The tougher the books, the more firmly he fixed a distance between himself and others.

He found enough that he could understand. He could see the capitalists, he could see the masses. They were right here, all around him, every day.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.