The following article is from the literary news site, Press Street: Room 220. The original article can be found here.

Writer Daniel Wolff came to New Orleans five months after Hurricane Katrina with filmmaker Jonathan Demme, not knowing what they’d find. They were told the story was over, that all the “good shots” had already been taken. But it seemed to them that there was a great, ongoing fight for survival that was just as important as the immediate tragedy that followed Katrina. So they started meeting people and making friends—then kept coming back. They thought they’d only do two or three visits, but six years later, they were still returning.

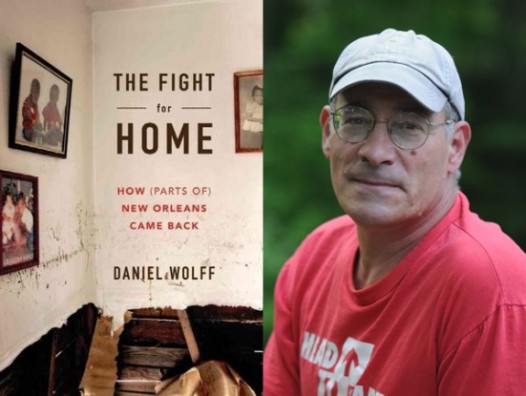

Wolff took notes the entire time, and in addition to the movie projects, decided to write a book. The Fight For Home: How (Parts of) New Orleans Came Back pieces together a tale of post-Katrina New Orleans through interviews with a range of different New Orleanians affected in various ways by the levee breach. The ex-drug addict turned preacher, the community organizer with a vision, the family man trying to renovate several properties, and others share a rich tapestry of stories that illustrates their struggles and work.

As a community organizer in the Lower Ninth Ward, where I was born and raised, I have heard so many stories that I am full. I am tired. Not because people’s stories are boring or repetitive, but because they are a constant reminder of the ills that still plague this country—and most people seem more interested in the stories and tales of woe than making any radical change. Still, the stories are immeasurably valuable. And so I also found this book comforting. Reading it was like a meditative reflection, an out-of-body experience, like watching parts of my own life that I didn’t even know about. Mostly, I appreciated that these people, some of whom I know personally, had their stories told. The book validates and respects their experiences, and therefore the experiences of all who were affected.

Life stories aren’t “good” or “bad,” and don’t have fixed “good” or “bad” endings. Life just IS. And so it is with The Fight for Home. The book isn’t meant to present solutions or provide salvation. It’s an empathetic telling of stories that ring true for thousands of New Orleanians. The value of books like this is that, after the tragedy that struck fades into obscurity, these stories provide evidence that those lives matter, that the tragedy DID happen and it DID affect real people.

It’s not often that I get to chat it up with the authors of the books I read. So I enjoyed Skype-ing with Wolff late one Friday night. If you want a chance to speak with him, Wolff will be appearing in a series of events this week in New Orleans in support of the book and one of the corresponding movie projects on which he collaborated with Jonathan Demme. On Thursday, Aug. 16, at 5:30 p.m., Wolff will present the book and answer questions at the Garden District Book Shop (2727 Prytania Street). On Friday, Aug. 17, at 7 p.m., he will be on hand at the Ashe Center (1712 Oretha C Haley Boulevard) for a screening of the film, I’m Carolyn Parker. Finally, on Saturday, Aug. 18, at 2 p.m., Wolff will present The Fight for Home and answer questions at the Community Book Center (2523 Bayou Road).

Room 220: I strongly believe that communities should tell their own stories—the people of the Lower Ninth Ward should tell the stories of the Lower Ninth Ward, for instance. But at the same time, if it’s not happening, the stories still do need to be told. What are your thoughts about that?

Daniel Wolff: I got out of the way as much as I could with this book, and I hope I did a good job. I’d say about 95 percent of it is in the voice of the people we talked to, not in my voice. Part of what interests me is creating a document in which people get to testify—they get to tell their story and present it. It’s not like every third paragraph I had to explain what all this meant or what they were doing. People had their own voices and had their own ways of telling the stories. I agree with you in principle, but on the other hand, if I let that stop me, as you said, these people’s stories don’t get told. I can’t turn myself into a native of the Lower Ninth Ward. So as difficult as it may be sometimes, and there’s a bunch of stuff I’m sure I miss, it seemed to me to be worth trying.

Rm220: Do you ever feel guilty about writing stories about people’s struggles with the intention of profiting off of them while they continue to struggle?

DW: Both with the movies and the book, we’ve gotten an awful lot of whatever little money we make back to the folks. I can assure you, there’s not much profit happening out of this. But on another level—and it’s a good question, Jenga—where I felt guilty, and I know Jonathan did, was just being able to get on an airplane and go back home after conducting interviews and have hot water and a shower, and all the other privileges the people we talked to lacked. That’s incredibly hard to do.

Rm220: What do you hope that readers get out of your book?

DW: I’m treading lightly here, but one of the things I wanted to communicate is that New Orleans isn’t special in a lot of ways. I know it is special in a lot of ways—and there are all sorts of distinctive things about it that you can’t find anywhere else in the world—but in terms of how it treats its poor people and its people of color, and the problems it faces related to having an economy that works and a health care system that works and a police force that works, it’s like a lot of cities in America. So I hope that when people in other cities read the book, they can go, “Well, this all sort of rings a bell. We didn’t have a flood, but the problems that these people faced are the problems that almost every big city in America is facing right now.” The problems in New Orleans were just highlighted by Katrina. If you put a flood through East St. Louis or Detroit or Baltimore, you’d see something very similar, I think.

Katrina anniversary, 2010.

Rm220: I’m curious about the process you used to select interview subjects. Who did you meet first, and how did that lead to the other people? In the Lower Ninth Ward, it seems like the people who are featured in the stories are in one particular area. Was that intentional?

DW: We didn’t have a plan at all. The way I got to that block in Holy Cross was through Antoinette K. Doe. We went to talk to her at the Mother-In-Law Lounge, and she said that she had grown up in Holy Cross. She told us a story about riding her bike through Holy Cross as a little girl. So we went back with her, and the first day of walking around Holy Cross with her, we came upon a bunch of people on that block over by Sister and Jourdan. Then we just kept coming back. What we did wasn’t rational, it was totally by the seat of our pants—it was who we bumped into.

Rm220: What did you notice about the people you came back to talk to over the course of several years? I ask because, eventually, people get tired of telling their Katrina stories.

DW: Part of the advantage of coming back to the same people is that we became friendly with them, and instead of it just being some stranger knocking on their door, we could say, you know, “What happened to that dog that you found on the street?” People opened up more and more to us, and rather than being irritated by having to tell that Katrina story over and over—which I know is hell—they weren’t telling the Katrina story anymore. We knew their friends and family and pets, and they were keeping us up to date on what was ongoing. And unlike the mainstream media coverage, they understood and we understood that the more important story was what was hard and challenging about trying to build a life again, and build a city again.

Rm220: How do you think community leaders and residents who want to see the Lower Ninth Ward be a better place can use the information in your book?

DW:Well, everybody already knows their own issues, because they’ve lived through them, but hopefully people can look at the book and realize that the issues were cutting across some class and race and social lines that they might not have been aware of, and that some progress was made in some places, while some of the things that didn’t work can teach a lesson, too. I think it’s sort of like: What do you learn from your scrapbook, or from your family history book, wherever you put the pictures from your grandma’s wedding? You learn that there’s a kind of continuum, and that this didn’t just begin last week and it’s not going to end next week—there’s some history to it all, and I hope the book helps fill in some of that history. The book isn’t a history of Common Ground, for example, but it’s the beginning of taking a look at it—and to me, that’s a very complicated story, a series of successes and failures and struggles, that there’s really a lot to learn from in terms of trying to organize.

Jenga Mwendo, the interviewer, is the founder of the Backyard Gardeners Network, which works to strengthen the community of the Lower Ninth Ward through urban agriculture. Here, Mwendo (standing) and other L9 community members share experiences in a story circle organized by BGN in one of the organization’s gardens in spring 2012.

Rm220: It was sad for me, reading about Common Ground and Malik [Rahim, Common Ground’s founder]. I think one of the values of a book like this is that, often, we don’t sit and analyze our history over the past few years—we deal with what’s coming up day to day, and we’re thinking about the future. The past is there, it’s led to what’s happening right now, but we don’t really think about it like that.

DW: Malik’s story with Common Ground is sad, but it’s also, to me, inspiring simply that he did it. He’s an amazing guy, Malik, and I think something like 25,000 volunteers have passed through the organization. They gutted a lot of houses and did a lot of work. As people say in the book, whether the organization changes or continues, there’s still all these kids who passed through it, who went back to cities all across America, who got an education that is extraordinary, and that’s because a bunch of people in New Orleans said, “No, we’ve got to do what the government isn’t doing,” essentially. And so, for these kids who took a year off of college, or whatever, that’s a more important learning experience in a year than they got in, you know, Yale.

Rm220: Yeah, it’s a big education for them, but that’s another thing that I struggle with—you know, who benefits more from their being here? We’re definitely appreciative of all the volunteers who come down to help, but if they were to take that money that they used for flights and all the things that they paid for to come down and actually gave it to the organizations that they came down to support, I wonder if the organizations might be better off.

DW: That’s a very good question. And I think one of the illusions, especially for volunteers and visitors, was that the city really did start over fresh once the floodwaters were gone. In fact, there was a long history, obviously, that clicked back in place right as soon as people started to rebuild. The old prejudices and difficulties don’t go away. I hope one of the things the book makes clear is that some people decided not to come back because they had better jobs elsewhere, and whatnot, but it was also made really difficult, as you know, for a lot of people to come back. One of the things I learned was that it wasn’t only that there was no place to live because the houses were all flooded. A bunch of different people in the book come to the same conclusion at some point, where it suddenly hits them, and they go, “I don’t think they wanted us back.”

Rm220: And then you wonder what that’s all about. Because so much of what makes New Orleans unique and makes people want to come to New Orleans was created by the very people that weren’t supported in coming back to New Orleans.

DW: Right. You wonder how you keep having a city that’s attractive to tourism—for example, if that’s what you want to build the economy on—if the people who are inventing the music and the food and the architecture and the culture in general aren’t there anymore. You worry about it turning into a Disneyland.

Rm220: And then what is there? It’s just a memory. And I wonder what’s going to happen. The city takes for granted all these things that make it what it is, and was just willing to let them go. I think New Orleans is trying to hold on to the musicians, definitely, because the city sees that that’s what people come here for, but outside of that I don’t see anything intentional being done in terms of keeping certain people here.

DW: I agree. And just keeping poor people, and giving them a better chance—never mind whether they can play a trombone—the city isn’t being good about that. The Lower Ninth, to me, and I’m not an insider like you, is an incredibly rich and brave place, and ought to be honored that way. And I think that would be a real radical change, if that happened—not just for New Orleans, but for the country—because where there’s the equivalent of the Lower Ninth in Philadelphia or Oakland, the same problem occurs. It isn’t honored.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.