To listen to Sharon Litwin’s interview with Erin Greenwald on WWNO radio, click here.

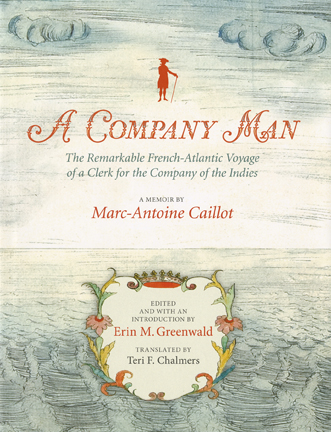

In 2004 the Historic New Orleans Collection acquired a remarkable document written by a 21-year-old French adventurer who came to New Orleans almost 300 years ago. This travelogue, one of the most significant finds of its kind in well over a hundred years, has been translated into English and is now in print as a book. A Company Man: The Remarkable French-Transatlantic Voyage of a Clerk for the Company of the Indies, was published by HNOC and edited by Erin Greenwald, one of its historians.

In 2004 the Historic New Orleans Collection acquired a remarkable document written by a 21-year-old French adventurer who came to New Orleans almost 300 years ago. This travelogue, one of the most significant finds of its kind in well over a hundred years, has been translated into English and is now in print as a book. A Company Man: The Remarkable French-Transatlantic Voyage of a Clerk for the Company of the Indies, was published by HNOC and edited by Erin Greenwald, one of its historians.

Erin began work on the document in 2007. With only the last name of the author available, she needed to find out more about who wrote this amazing 184-page uncensored French document, with its 13 original watercolors. It took her five years working with translator Teri Chalmers before enough information was gathered to publish the manuscript as a book.

“The author’s name is Marc-Antoine Caillot,” says Erin. “He is the eldest son of a family that was very closely tied to the King’s household.”

In fact, Erin discovered, Marc-Antoine Caillot was born into the household of the Dauphin, the eldest son of Louis XIV, where his father was a footman. When the Dauphin died, the Caillot family stature was greatly diminished. So Marc-Antoine did what many in such circumstances did: He found a patronage position. His was as a bookkeeping clerk with the French Company of the Indies.

Between 1717 and 1731 the French Company of the Indies possessed a monopoly in Louisiana, controlling the slave and Indian trades while attempting to establish a tobacco culture. In 1729, Natchez Indians destroyed any hope of a tobacco empire when they killed more than 200 Frenchmen upriver. By 1793, the company had abandoned Louisiana, giving all control to the King of France.

Caillot started out in the Company of the Indies’ office in Paris. He was offered his first commission to Louisiana in 1729, and stayed in New Orleans until 1731, when the Company pulled out of the state. For the entire two-year period he was in this city, Caillot documented much of what he observed, writing in a style he had begun on board ship.

It was very important to Caillot, Erin explains, that he always appear to be funny and witty and clever. And, she discovers, he is happy to be all of those things even at the expense of others.

“He’s just a real rascal,” Erin says. “And quite the lady’s man. So we get this really wonderful sense of what it was like to flirt and tease in the 18th century.”

Caillot’s descriptions of life in the earliest days of New Orleans, along with those of a variety of animals inhabiting the surrounding areas, are both amusing and fanciful. His roguish adventures range from cynically winning the heart of some unsuspecting, less-than-beautiful woman on board the New Orleans-bound ship to crashing a wedding party on Bayou St. John.

In many ways, Caillot is not unlike some of today’s boy-will-be-boys teens with their pranks and jokes. But his unique and personal glimpse into an 18th-century life rife with its many dangers and unknowns adds a layer of fascination for 21st-century readers.

As part of the celebrations accompanying the release of the book, the Historic New Orleans Collection, 533 Royal Street, will present an exhibition called “Pipe Dreams,” opening on June 18, 2013. For more information on the book and the accompanying exhibition, go to www.hnoc.org, or call 504-523-4662.

Erin also will be signing her book on Tuesday, June 18, from 6:30 to 8 p.m., at the Cita Dennis Hubbell Branch of the New Orleans Public Library in Algiers Point, 225 Morgan St. Visit www.hubbelllibrary.org for details.

Meanwhile, enjoy these some excerpts from A Company Man:

Marc-Antoine Caillot’s descriptions of Bayou St. John:

In Bayou Saint John there are fish, namely mullet, sun perch, angelfish, which have two sort of wings, magnificent crawfish and little turtles. At the end of the bayou is Lake Pontchartrain, in which there are swordfish. These animals fight the whale, even though they are much smaller. At the end of their head they have, in effect, something like a sword blade, which is ten to twelve inches wide and about seven to eight feet long. With this they can cut fish cleanly as a razor. They are not worth eating. What they are good for is oil for burning. In this lake there are fish called flounder, salmon trout, a type of sardine, passeau, rays, and even porpoise.

And then there is his journey on the bayou:

One day I was on a pleasure excursion with some of my friends on Bayou Saint John … We had brought as provisions some good pate, a few dozen bottles of good wine, and some cured meat from the butcher’s in order to spend the day at the home of a certain Joseph Bon, inhabitant of said place, who lived on the other side of the aforementioned bayou. In order to go to his house, we got into our little pirogue with our provisions. We were only halfway there when, all of a sudden, a huge crocodile came and put his two front feet on the edge of our little boat, which he almost turned over, to get our meat. We were in a great deal of trouble, so, in the meantime, having loaded our muskets, together we all shot him in the head and blasted out his eyes. He left us making a terrible turbulence in the water …

Sharon Litwin is president of NolaVie. Email her at sharon@ nolavie.com.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.