By Michael Allen Zell

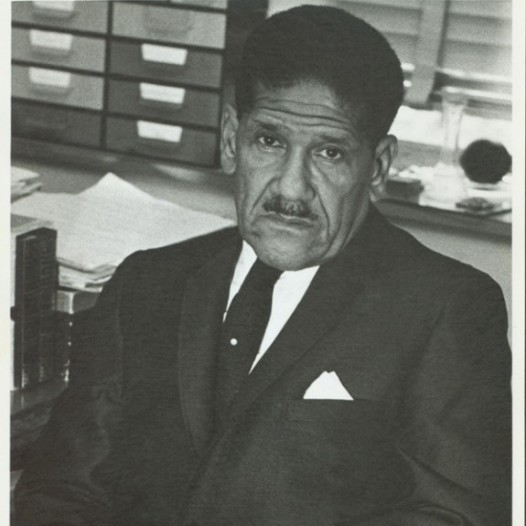

Image courtesy of the Marcus B. Christian Collection, Earl K. Long Library, University of New Orleans

The best way to keep a secret is out in the open, and so it nearly is for a particular author/historian/folklorist largely unknown to even the literary-minded in New Orleans. He wrote thousands of poems, plays, short stories, articles, and historic pieces until his death in 1976, provided content on street vendors and slaves forGumbo Ya Ya, corresponded with luminaries such as Eleanor Roosevelt and Langston Hughes, compiled a 1,000 plus-page history of black Louisiana, and saw his poem “I Am New Orleans” printed on the front page of the Times-Picayune’s 1968 sesquicentennial edition.

One might think I am writing about an imaginary man, for how otherwise could this mountain of material be almost entirely unfamiliar and out-of-print (if ever available)? But this man is no John Henry and certainly not a Darger-esque outsider artist. Instead, meet Marcus B. Christian (a man who, by the way, spent more than two years researching John Henry’s existence beyond folklore).

Christian’s Negro Ironworkers of Louisiana, 1718-1900, his only in-print title, and the other thin scarce books—what Lawrence Durrell might call concertina pieces—do not go so far as hint at what sits tombed, well-catalogued, and mostly undisturbed in the University of New Orleans’ Special Collections. His general biographical framework, available via the KnowLa online encyclopedia, takes us from his Terrebone Parish birth to a lifetime in New Orleans, and from his supervising the Negro History Unit of the Louisiana Writer’s Project at Dillard University to an undue dismissal there, and the eventual ending of his career at the University of New Orleans. What concerned me as I read through and skimmed an afternoon’s worth of manuscripts, broadsides and handbills, correspondence, and diary pages from the Christian collection—a scant introduction to the estimated 146 linear feet worth in the archive—is that this mountain has not seen itself avalanched to interested readers and historians.

Was Christian a man mismatched for his time? Is his ongoing obscurity due to standard literary neglect, the quality of his work, lack of marketability, or bigotry due to his race? These accumulating questions can only be answered with the bold but frank rejoinder: What does it matter?

I’m not trying to be glib—this is a serious response. What does it matter? Historical archives throughout New Orleans are stuffed with interesting and quality documents. Most writers attempt to take necessary steps to inch head above shoulders only to find their eyes met by countless others. Christian had his day, some might say, but now the glow’s worn off.

Poet and scholar Dr. Jerry Ward, Jr.—whose The Katrina Papers is, in my view, the strongest micro-view book on its subject—has this to assert: “Reasons for exploring Marcus B. Christian’s poetry, diaries, and historical writings are very well explained in Tom Dent’s essay ‘Marcus B. Christian: A Reminiscence and Appreciation.’ Christian’s influence on Dent and Arthur Pfister draws attention to tradition. We speak endlessly about music in New Orleans and far less about the city’s literary traditions which incorporate a special sense of Louisiana history. Christian’s work is a model of what needs to be done from twenty-first century angles.”

It is with intention that I attempt to shed light on Marcus Christian’s work in the first of my monthly columns. Here’s a laundry list why he matters:

To me, the work of this “small man with a big voice,” as he was described in a 1970 Times-Picayune piece, wears very well with the test of time. It is always heady, gritty as necessary, and resonates with life. We could do far worse than to resurrect the Lazarus called Marcus Christian, whether laypeople by general awareness, readers/writers by reading and learning more about him, and publishers by making his work available. Christian began Escape At Thirty-Five with, “I’m tired of fighting back – I long for peace; I wish to draw unto itself my soul.” I encourage you to take a little time on behalf of an author who, though tired of fighting, continued to fight on while hand-cupping his soul like a candle and holding it high.*

*a paraphrasing of two lines from Marcus B. Christian’s Hieroglyphs on Granite.

This article is reposted from Room 220, a content partner of NolaVie. “Stray Leaves” is a recurring series of articles written by Michael Allen Zell that illuminate oddities and rarities from New Orleans’ literary history. ”Stray Leaves,” in Zell’s words, is “a lifting up of stones and crowing about that found underneath, led by the guiding notion that we are standing on the shoulders of writers and books that deserve their names and faces returned to the public.”

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.