By Ari Braverman

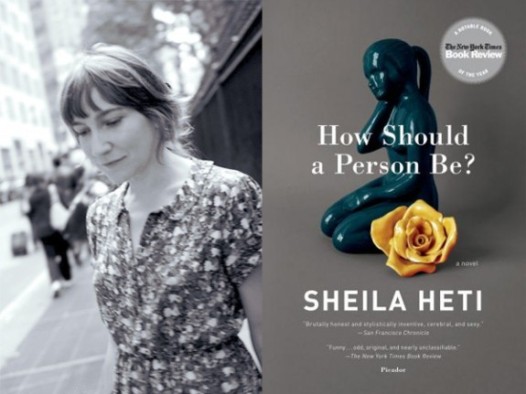

Sheila Heti’s third book, How Should a Person Be? is about Sheila. The character is a Toronto-based writer grappling with a play she can’t seem to finish, stuck in a marriage that stifles her. Enter Margaux, a peroxide-blond painter who “looked at the same time like a little girl, a sexy woman, and a man.” What follows is the story of a friendship between two people who happen to be artists, who happen to be women. Through their conversations and their adventures–things like taking a trip to the ice cream parlor, sharing studio space, traveling to Art Basel in Miami, buying the same yellow dress–Sheila arrives at her own answer to the titular question.

Sheila Heti’s third book, How Should a Person Be? is about Sheila. The character is a Toronto-based writer grappling with a play she can’t seem to finish, stuck in a marriage that stifles her. Enter Margaux, a peroxide-blond painter who “looked at the same time like a little girl, a sexy woman, and a man.” What follows is the story of a friendship between two people who happen to be artists, who happen to be women. Through their conversations and their adventures–things like taking a trip to the ice cream parlor, sharing studio space, traveling to Art Basel in Miami, buying the same yellow dress–Sheila arrives at her own answer to the titular question.

The book is mystifying and exciting in a quiet, internal way. This comes from the piece’s main conceit: characters that are named (and modeled) after real-life counterparts. Heti includes transcripts of real conversations and email threads between herself and her real-life best friend, Margaux Williamson. She jettisons the traditional idea of narrative for an episodic structure that mirrors what she has called “the messiness of life.” Instead of alienating the reader, these personal fragments make the book accessible. Sheila’s experiences are specific, but her thoughts and feelings are familiar. Because she communicates through a pantomime of the personal, Heti forces the reader to contend with questions of love, identity, and authenticity on an intimate, uncomfortable level.

The Heti I’d read about in other articles seemed like all the things a writer should be: self-assured but humble, articulate and accomplished. In the photos I Googled, it even looked like she had impeccable taste. My image of her was all I could think about when I dialed her number. But when she answered, she immediately put me at ease. I could hear birds in the yard outside her Toronto home. She asked me about myself and laughed a lot. I realized yes, the individual on the end of the line is the originator of books, ideas, and the writer Sheila Heti, but she’s also a person. Like Heti said in our interview, “No one is an exception.” Everyone is a self and everyone is a character.

Heti will present How Should a Person Be? to celebrate its paperback launch with a reading at 6 p.m. on Saturday, June 29, at Octavia Books (513 Octavia St.). For more local coverage of the event, see Chris Waddington’s article at nola.com.

Room 220: What do you think is the difference between memoir and autobiographical fiction?

Sheila Heti: I think memoir is about one’s identity. I’m not so interested in identity. I’m more interested in the self. I feel very palpably that my identity and my self are really different things—and for me the self is the interesting part. That’s the part that could be God. It could be all humans. It could be nothingness. It could be anything. Identity is really clear—what it is. I have no questions about what my identity is—I’m a thirty-six year old woman living in Toronto. But the self seems very different. It’s not something you can catch. It’s always shifting and it encompasses more than just one self, more than just your self.

Rm220: Why did it feel important to you to write a piece like this, with so much of the narrative structure and characterization drawn from your own experience?

SH: I just think there’s something so strange about the idea that a person writes alone. You don’t raise yourself, you don’t kill the food you eat, you don’t educate yourself. Everything we do is bound up in everything other people do. I think about Crime and Punishment. We think of that book as something Dostoyevsky did on his own, and it’s true, he did—and a very simple story of a writer working alone was my inherited idea of the artist. But over my life, I’ve seen that it’s wrong. Artists get ideas from other people, suggestions from other people, and encouragement. As though Flaubert came up with his ideas by himself and not through conversation with everybody he knew and from being in the world, from reading the newspaper. That’s just the way everything works. I wanted the structure of my novel to be honest about that aspect of how art is made—and how this book in fact was made.

Heti and her best friend, Margaux Williamson

Rm220: Did you think about future readers as you were writing the book?

SH: I was never wondering, “Is somebody I don’t know going to have a problem with this?” My main audience at the time was Margaux, and I knew what she thought of the book because she would tell me! I remember giving her this huge, six-hundred page draft to read a couple years into writing it. I was so excited. She took it on vacation with her and I couldn’t wait for her to get back. I remember the day I gave it to her. I felt like I was giving her a ring, I felt so lit up and excited for her reaction! And she didn’t like it. She was really disappointed. She had all sorts of problems with it. At that point, I felt I had to make the next draft a draft she would like, which is different from making a book some abstract audience would like. I love Margaux. I wrote the book as a gesture of love. And such a book would also not be different from a book that I would love, because we had the same aesthetic goals at the time.

Rm220: What were those goals?

SH: So many things. To make something without using resources in a wasteful way. To try and understand each others’ ideas about art and life more completely. For instance, I had this very Platonic view of the world. Margaux didn’t feel that way.

Rm220: It’s interesting to hear you say you have a Platonic idea of the world because the book is so much about destroying that.

SH: Exactly. When I was writing this book, I was going against my instinct to try and make some Platonic form. I’m more confused now because I’ve learned about the value of going against your instincts. All my life, I thought the way to live was to follow your instincts, but now probably the most personally transformative project I’ve worked on came out of going against my instincts. The discomfort with writing this book and the discomfort of—at times—our friendship, turned out to be a very good for our lives and our work. But surely there are times where you go against your instincts and it’s not beneficial. It’s horrible, it’s painful, and it doesn’t lead to anything good. How can you tell which one you’re doing? I think you can’t tell until the experience ends. Margaux doesn’t think you can learn lessons from one experience and apply it to other experiences, because every experience is different. But that’s all I ever want to do! You just want to know: Is this a good rule to follow? Is this the way to go forward? But it doesn’t work that way.

Rm220: The form of your book reflects that difficulty. Of course it has an internal logic and of course there is a narrative, but on the surface it rambles.

SH: It was a search. Formally, I wasn’t trying to write a novel for a very long time. I was just writing. For years, I wasn’t thinking, “I’m going to write a great book” or “I’m going to write a bad book.” I was trying to understand different things, and I was trying to understand them by writing them down. When I wrote the sex chapters, for example, I wasn’t imagining I was going to publish them. I just wrote them. So I had been writing this way for a number of years, and then the first draft took form in one night.

Ticknor, the novel before How Should a Person Be? was formally very tight, and after that, I didn’t feel the need to prove to myself that I could make something tight. And Ticknor had been a reaction against The Middle Stories, because after I published that, people kept implying that I was going to write these short fairy tales or whatever forever. I always feel a lot of contempt for what people think about me, and I said, “I’m never going to write like that ever again. This will be the exact opposite. You don’t know me!” I think a lot of negative emotion goes into why I make some artistic choices. “You don’t know me.” That’s a really weird motivation for a book!

Rm220: Do you feel that motivation now?

SH: Not so much. But people keep sending me these autobiographical novels to review! And it’s not correct—I was never interested in this as a genre or thinking about this genre. I just like good writing. Maybe a certain book happens to be good writing, maybe it doesn’t. But the autobiographical genre doesn’t interest me in itself. I mean, it doesn’t have to be “autobiographical” to talk about life. All novels are basically saying, “This experience is also human,” or “This life is no less of a life.”

Rm220: People talk about how books like this one run the risk of being really self-indulgent and maudlin. How does a writer avoid all that?

SH: I think it has to do with the writer’s motivations. And also, there’s something to be said for this: Some people are just very good writers. For instance, I’m working on a book right now with some other women, and we’re getting in surveys with people’s answers to a questionnaire we’ve sent out. Lena Dunham was one of the people we asked to fill out the survey, and her survey is just so fucking good. It’s so smart, it’s so funny, it’s so interesting, and you just want to read it for a hundred pages. She’s just a really good writer. I’m talking about her right now because people had a lot of jealousy, asking, ‘Why her? Why her? Is it because she lives in New York?” After reading these surveys, I wanted to say to the people who were saying that, “You don’t know what your HBO show would be like.” Maybe it would be great. But on the other hand, you read her survey and it’s like, “No. She’s a really fucking talented writer.”

You can say that Wayne Gretzky is a really talented hockey player, and the same goes in art. Talent is real—like height is real. I think it comes down to how a person’s mind works. Does their mind work in a way that’s beneficial to writing literature? Are they stupid in the right ways? Are they smart in the right ways? Are they ignorant in the right ways? Talent is probably just a combination of helpful stupidities and helpful intelligences and helpful dispositions.

Rm220: It’s interesting to hear you talk about talent as this luck-of-the draw combination of characteristics. It makes me think about authenticity. There’s not authentic talent, like there’s not some authentic narrative arc. Would you tell me about your idea of authenticity?

SH: Authenticity doesn’t make any sense as something to strive for. Because the question is, authentic to what? Authentic to your feelings, your instincts, your moral code? All of these things are constantly in conflict. That’s the human condition, negotiating the fact that these things often point in different directions. You can’t be authentic, because even if you are, say, authentic to your instincts, you’re maybe being inauthentic to your moral code. Is that why Jesus is such an example of goodness—because his morality and his instincts and his feelings and all that stuff all pointed in the same direction? I think that kind of simplicity is what makes him a beautiful character, because that’s a fantasy, and that’s the fantasy of being a truly good and great and transcendent person. But modern literature really is the story of inner conflict, and it’s the conflict, I think, of never achieving authenticity. Because no one lines up that simply.

Andy Warhol is interesting because “Andy Warhol” was a construction, an artistic act. The real man was not what he gave us. I think the culture right now understands that the self can be an artistic act, a creative act, a deliberate act. And maybe it’s not immoral because maybe there is no “true self” that’s being betrayed. The hippies—they were all about “being real.” When was the last time somebody said to you “Be real, man?” Every era is wrong in its own way, but that’s kind of fun! Maybe I’m wrong about authenticity, but it’s fun to be wrong in the way your era is wrong.

Rm220: Why do you think so many people responded to this book?

SH: When I was writing this book, I was thinking deeply about what was happening in the mainstream of culture. I was thinking about Paris Hilton, I was thinking about reality TV. So for probably the first time in my life I was in sync with what other people were thinking about while I was writing my book, so it makes sense that when the book came out it was in the same place that other people were. Before this book, I was terrified of putting pop culture into my brain. If it wasn’t for Margaux, I might never have done that.

Also, I wanted this book to be accessible. I remember I was working at a hair salon and this older woman, a client, said to me, “I’ve read your books but they went completely over my head.” That made me really sad. I didn’t want my books to go over this lovely person’s head. So I was trying to write a book that you wouldn’t have to be a certain kind of person to read. Because no one’s an exceptional case. The things that happen to one person happen to other people, more or less. That’s just faith in “the human experience.” You have friendships, you have something you try and apply yourself to, you have sex, you experience being in a body moving strangely through time.

I wanted the book to feel like it was moving around in your life or that you were moving around inside it. I didn’t want it to be a static story on the page that you would visualize in your imagination and afterwards think, “What a great story that was.” I wanted it to feel like part of your life. I wanted it to be an encounter rather than a narrative. I had that in my mind from the beginning. I was thinking a lot about the sculptor Richard Serra. He had this line about wanting to take sculpture off the pedestal. He creates these huge site-specific projects—one of the ones I kept thinking about was in Manhattan, called “Titled Arc.” A few office buildings faced each other around a very large courtyard. Serra spent a long time watching the paths people took when crossing from one building to another, until he finally found the one main route that people used. It traced this sort of arc, and he put up a gigantic steel curving wall so people could no longer walk along that path. People were so mad at it! They pissed on it and they wrote on it. They defaced it. He really hated that they did that, but on the other hand he deserved it. He was interrupting their lives. He was making it hard to walk. That’s the kind of novel I was trying to write. Not a sculpture on a pedestal but something else. I wanted to make it hard to walk—hard for someone to walk down the same path they use every lunch hour.

This article by Ari Braverman is reposted from Room 220: New Orleans Book and Literary News, a content partner of NolaVie.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.