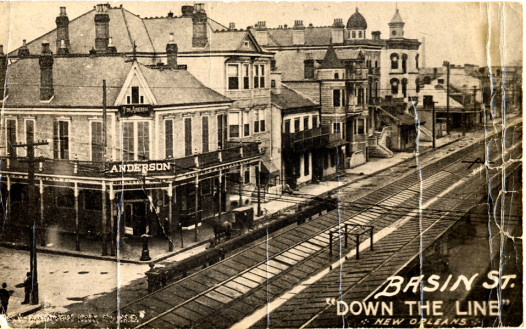

This 1908 postcard shows the rail lines on Basin street which carried visitors into the heart of Storyville, New Orleans’s vice district, credit: Louisiana State Museum

As part of a new collaboration with the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, NolaVie will spotlight entries from KnowLA.org — the Digital Encyclopedia of Louisiana, including unique events and people in our state’s history.

This month, we commemorate the end of Storyville. On November 12th, 1917, Mayor Martin Behrman acquiesced to pressure from the US Navy and ordered the red light district closed at midnight. Here’s the story, written by Emily Landau.

Created by municipal ordinance in 1897, Storyville was New Orleans’s infamous red-light district. It remained open until 1917, when the federal government shut it down as part of a nationwide crackdown on vice districts. While Storyville was only one of many red-light districts during these years — every major and most minor American cities hosted at least one such district — it stood out for several reasons.

First, New Orleans had long maintained an international reputation for sexual license and a flamboyant disregard of traditional morality. Storyville’s notoriety perpetuated that image of the city and raised it to a new level. Second, New Orleans’s history as a French, and then Spanish, colonial city lent it a foreign feel, even after nearly a century of American rule. This foreign-ness, along with its subtropical climate and large mixed-race population, made New Orleans an exotic enclave within the Deep South.

Storyville took advantage of the city’s colorful history by promoting the availability of both “French” and “octoroon” women in its guidebooks and through tabloid press. “French,” in the context of a sex district, signaled special sexual services; women purported to be one-eighth black were available for the exclusive use of white gentlemen, recalling the antebellum quadroon balls. In addition to so-called octoroons, Storyville further violated the segregation laws by advertising “colored” and later “black” women for the use of white men. Sex across the color line was, according to a prominent citizen in the 1910s, Storyville’s “notorious attraction.”

Finally, Storyville nurtured the development of jazz by employing musicians in its brothels, honky-tonks, saloons, and dance clubs. Perhaps more than anything else, Storyville’s association with jazz has assured the district’s prominent place in American history. Though the music itself was considered disreputable at the time, the nearly universal recognition of jazz as a genuine and authentically American art form has lent Storyville a nostalgic aura and rosy glow that it does not necessarily deserve.

Establishment of Storyville

Storyville, despite its reputation as the nation’s most notorious red-light district, was created to curtail and contain the spread of prostitution in New Orleans. The men who occupied City Hall at the time of its creation had recently ousted the Democratic ‘Ring’, a corrupt political machine that held the city in a tight grip, and were eager to reform the city. As self-styled progressives, they wanted to root out corruption and attract both capitalists and tourists to the Crescent City. Led by Mayor Walter C. Flower, a cotton merchant who was, in his own words, “thrown into politics,” these elite businessmen sought to clean up the city: literally — through proper sewerage, drainage, and clean water facilities, and metaphorically — by limiting vice to a few isolated neighborhoods.

The original ordinance (No. 13032 C.S.) reads:

From the first of October, 1897 it shall be unlawful for any public prostitute or woman notoriously abandoned to lewdness to occupy, inhabit, live or sleep in any house, room or closet without the following limits: South Side of Customhouse [Iberville] from Basin to Robertson street, east side of Robertson street from Customhouse to Saint Louis street, from Robertson to Basin street.

Yet the ordinance also included the proviso that: nothing herein shall be so construed as to authorize any lewd woman to occupy a house, room or closet in any portion of the city. Thus, the city gave itself the authority to regulate prostitution without technically legalizing it.

In 1900, the Democratic Ring regained power and dominated city politics for the next twenty years. Rather than close Storyville, they continued to profit from prostitution until the U.S. Navy forced its closure. Indeed, one of Storyville’s most powerful figures was Thomas C. Anderson, who, in addition to operating several saloons, was a senator in the state legislature. He had a long history as a ‘boss’ where prostitution was concerned; Before Storyville, prostitution was centered in an area known colloquially as ‘Anderson Country’.

Storyville’s roughly thirteen square blocks bordered both the French Quarter and the rapidly developing business district, known as the American section. In 1897, the neighborhood had a mixed population of blacks, whites, Creoles, immigrants, young people, and old. There were widows, workingmen, artisans, city court clerks, and prostitutes. Small businesses — Italian fruit stands, corner groceries, a ‘Chinese laundry’, two ‘Negro dance halls’, two churches, a school, and several houses of prostitution and assignation — also populated the area.

In July 1897, months before the ordinance was to take effect, the city council amended the boundaries of Storyville to include St. Louis Street, which had originally constituted a kind of border between vice and respectability. George L’Hote, whose home and business occupied several blocks nearby, sued to prevent the extension. Though in favor of the original ordinance, he charged that if St. Louis Street were included, his family would have no decent path to and from their home. The Supreme Court decided for the city, and Storyville opened officially in 1900, after two years of de facto operation. The same ordinance (No. 13,485 C.S.) also created another red-light district. Known as “uptown” or “black” Storyville, this four-block district was bounded by Perdido, Locust, Franklin, and Gravier streets. Louis Armstrong grew up there.

Culture of Storyville

It was clear almost immediately that the district’s creators’ plan had backfired; Storyville made prostitution and sporting culture more visible and cemented the city’s reputation for promiscuous pleasure and illicit sex. The district gained international notoriety. Storyville’s promoters (probably led by Anderson) even published guidebooks. Known collectively as the Blue Books, they listed the brothels and the women within the area according to race: ‘W’ for white, ‘C’ for colored, and ‘Oct.’ for octoroon. Some editions listed ‘French’ and ‘Jewish’ women. The Blue Books also carried ads highlighting bordellos and other nightspots, like Anderson’s saloons, as well as ads for liquor and for pharmacists peddling cures for sexually transmitted diseases.

The district’s most famous madams included Lulu White, Willie Piazza, Josie Arlington, and Emma Johnson. Lulu White published her own ‘souvenir’ booklet for Mahogany Hall, her Basin Street bordello. The bordello featured a marble staircase, four floors, two parlors, fifteen bedrooms — each equipped with a bathroom, and an elevator built for two. Also called, ‘The Octoroon Club’, Mahogany Hall was infamous for its so-called Creole beauties. Not all the brothels were so luxurious, however; many rooms included only a bed and a washstand.

Storyville is often cited as the birthplace of jazz. Though jazz developed throughout New Orleans, Storyville provided work for local musicians. It was an entertainment district, with barrelhouses, saloons, dance halls, and other venues — many of which featured live music. Jelly Roll Morton, Bunk Johnson, Manuel Manetta, ‘King’ Oliver, and a young Louis Armstrong, among others, played in Storyville. Spencer Williams, who wrote “Basin Street Blues” and “Mahogany Hall Stomp,” was Lulu White’s nephew and lived at her bordello for a while.

Storyville’s Demise

As New Orleans developed, Storyville’s ‘back o’ town’ location became more central. In 1908, the train terminal at Canal and Basin streets — one block from Storyville — was completed. To reach the station, trains traveled past the Basin Street bordellos, where the (often naked) prostitutes waved to the passengers from balconies. Different citizens’ groups attacked Storyville, urging the mayor to close, or at least move, the district. To some, Storyville represented a threat to young women; to others, Storyville threatened the racial order.

In 1917, the city attempted to relocate all nonwhite prostitutes to the uptown district. Several madams, including Willie Piazza and Lulu White, fought the measure and won. The city reworded the ordinance, but before it went into effect, the district was abolished. Storyville was less than five miles from the naval training station, and when Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels made clear his desire for Storyville to close, Mayor Martin Behrman acquiesced, ordering it closed by midnight November 12, 1917.

Prostitution continued, but Storyville lost its cachet and the neighborhood declined. The photographs of E.J. Bellocq have immortalized some of Storyville’s women. Similarly, numerous films, bars, and clubs celebrate and romanticize the district, though it is physically gone. Following passage of the 1937 U.S. Housing Act, the city razed most Storyville buildings in order to construct the Iberville housing project. ‘Uptown Storyville’ now contains some hotels, parking lots, offices, and municipal buildings, including City Hall.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.