With all the changes in the downtown landscape, this month’s partner entry with Knowla.org, the Digital Encyclopedia of Louisiana, takes a look at the groundbreaking firm that reshaped the skyline: Nathaniel Curtis and Arthur Davis, architects of the Superdome.

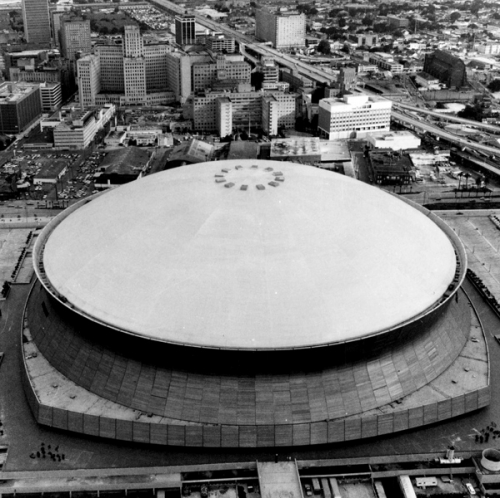

Pictured: An aerial view of the Superdome in the 1970s. The Louisiana Superdome, home of the New Orleans Saints football team, has hosted more Super Bowls than any other stadium. Designed by the Curtis and Davis architectural firm as a multipurpose arena, the Dome remains among the largest buildings of its kind in the world. Photo: Knowla.org

In 1947, Nathaniel Cortlandt Curtis Jr. (1917–1997) and Arthur Quentin Davis (1920 – ) established the architectural practice of Curtis and Davis Architects and Engineers in New Orleans. Until the partnership was dissolved in 1978, Curtis and Davis designed almost 400 buildings on four continents. They received approximately one hundred design awards, and their work was featured regularly in major architectural journals. Their projects encompassed the full range of building types: residential, educational, commercial, religious, recreational, and institutional.

Both architects were born in New Orleans and graduated from Tulane University, Curtis in 1941 and Davis in 1942. Davis also earned a Masters in Architecture from Harvard University in 1946, studying under Walter Gropius. The two established their office with a commitment to modernist aesthetics and to employ and express the new technologies and materials.

Projects in Louisiana

Their first projects were primarily houses and schools in Louisiana. Between 1949 and 1959, Curtis and Davis designed the Moses, Shushan, Taylor, Upton, and Halpern houses, all in New Orleans and its suburbs. They also designed residences in New Orleans for their own families (Davis in 1952 and 1955; Curtis in 1963). The Steinberg House, built in 1958, fully represents their ideas about contemporary residential design. This one-story, steel-framed, brick-faced house is slightly raised from the ground so that it appears to float. Its composition and details are horizontal in emphasis, while the interior courtyard draws on French Quarter traditions. The firm’s use of modern structural methods and forms that were adapted to the particular geographic and climatic conditions of place—in Louisiana, soft soil, flooding, intense heat and humidity—remained a hallmark of their designs.

To mitigate Louisiana’s heat and humidity, Curtis and Davis utilized traditional elements of southern architecture, including roof overhangs to shade walls and cover walkways, cross-ventilation, and window screens that protected interiors from heat and glare. To minimize the risk of flooding, they often elevated buildings above the ground. Several of these features were integrated into their design for the Thomy Lafon School, built in 1954, in New Orleans. Widely publicized and recognized with a National AIA [American Institute of Architects] First Honor Award, the school brought the firm national attention, as did their design for the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, completed in 1956.

The December 1954 issue of Architectural Forum describes Angola’s pinwheel scheme as “A New Kind of Prison” and as the first major departure from standard prison architecture. Curtis and Davis used Angola as an opportunity to expand their structural vocabulary. In particular, they employed lift-slab construction for the walls to dispense with the carpentry formwork required for poured concrete. The dining hall (now used as a recreation center) is a 76,000-square-foot area spanned by a double-curved roof. Each span measures 200 feet of prestressed concrete hinged at the center. Subsequently, Curtis and Davis became a national leader in prison design, responsible for more than fifty jails, correctional facilities, and youth centers throughout the United States.

In the New Orleans area, their designs included the main branch of the city’s public library (1958), which featured exterior metal screens over the windows to filter light and sun. They also designed the G. W. Carver School in 1958; William J. Guste Housing in 1964; and the Immaculate Conception Church in Marrero, built in 1957. The firm also completed numerous commercial buildings, among them the Caribe Building, built in 1958, and the Automotive Life Insurance Company, built in 1963, as well as hotels and motels. Within Louisiana their projects included Madison Parish Hospital in Tallulah (1957), the Louisiana National Bank (1968) in Baton Rouge, and Our Lady Queen of Heaven Church (1971) in Lake Charles. But their commissions increasingly came from areas beyond the state.

Projects Outside Louisiana

By 1960, the Curtis and Davis firm included forty employees and had opened branch offices in New York City, Los Angeles, London, and Berlin to supervise their growing national and international practice. Projects from the New York office included the Worcester, Massachusetts, public library in 1964, and two schools in New York City in the 1960s. The 1960s also saw the completion of some of their most important and structurally experimental projects.

Among the several buildings they designed for International Business Machines (IBM), the most innovative was the IBM Building in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, built between 1961 and 1963 (now known as the United Steel Workers Building). In September 1962, Progressive Architecture hailed the IBM Building as “one of the most unique office structures to be designed since plans for the United Nations Secretariat tower were completed in the late 1940s.” The thirteen-story structure’s exterior load-bearing, truss-frame wall of welded steel in a diamond-patterned grid was a radical break from post-and-beam construction. Built in collaboration with U.S. Steel, it used less steel than the traditional skeleton frame construction and directed all wind and wall loads to eight points at ground level.

Contrasting with the machine aesthetic of the IBM building is Curtis and Davis’s textured concrete design (developed with the firm of Fordyce and Hamby) for the James F. Forrestal Building on Independence Avenue in Washington, DC. Dedicated in 1969 for the U.S. Department of Defense, the structure is now occupied by the Department of Energy. The firm also designed the U.S. Embassy in Saigon, Vietnam, a building that had a long and complex history. Their first designs date to 1955 but, following the entrance of the United States into the Vietnam War, the embassy required more advanced security systems. Completed in 1966, it is perhaps best known for the 1973 airlift that took place from its roof.

In 1959, Curtis and Davis were awarded the commission for the Steglitz Medical Center of the Free University in West Berlin, Germany. Financed in part by Marshall Plan funds, the center was the largest medical complex in Europe at the time. It comprised a 1,426-bed hospital, facilities for outpatients, a medical school, and housing for nurses. Under construction when the Berlin Wall went up, the hospital opened in 1968.

Later Projects

Particularly important was the firm’s design for Rivergate, a convention center in New Orleans. Built in 1968 and demolished in 1995, Rivergate was the most innovative building—both structurally and aesthetically—constructed in twentieth-century New Orleans. Nathaniel Curtis was the principal designer for this structure, which was built in collaboration with the New Orleans’ firms of Edward B. Silverstein and Associates and Mathes Bergman and Associates. Measuring 452 feet in length, the Rivergate’s thin-shell concrete roof had an interior span of 225 feet. It is thought to be the longest single span of prestressed, post-tensioned concrete then built. Also structurally audacious was the Superdome, built in collaboration with the New Orleans firms of Goldstein, Parham and Labouisse with Favrot, Reed, Mathes and Bergman. With an internal diameter of 680 feet, it was the world’s largest clear-space steel dome when completed.

By the 1970s, the large and complex projects that Curtis and Davis accepted often gave them less opportunity to be innovative, sometimes resulting in generic design solutions. In 1978, the firm merged with Daniel, Mann, Johnson and Meldenhall (DMJM). While Davis went with the new firm, Curtis set up an independent practice, where he remained until his death in 1997. In 1988, Davis left DMJM and opened Arthur Q. Davis FAIA and Associates.

Curtis and Davis always kept current with new trends, both structural and aesthetic, often producing strikingly original designs. The architects’ New Orleans origins instilled a particular sensitivity to adapting architecture to difficult climatic and structural conditions wherever they designed. The Curtis and Davis firm had a reach and influence far beyond the state, and is considered one of the nation’s most significant architectural firms in the second half of the twentieth century.

Karen Kingsley

Tulane University

Suggested Readings

“The Architect and His Community: Curtis and Davis.” Progressive Architecture 41 (April 1960): 141–155.

Curtis, Nathaniel C., Jr. My Life in Modern Architecture. New Orleans: University of New Orleans, 2002.

Curtis and Davis Office Records. Southeastern Architectural Archive, Tulane University Libraries.

Davis, Arthur Q. It Happened by Design. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009.

“Design Firm Case Study: Curtis and Davis.” Interiors 126 (February 1967): 101–147.

“Jeunes Architectes dans le Monde.” L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui 73 (September 1957): 82–85.

Kingsley, Karen. Buildings of Louisiana. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Suggested Links

“Nathaniel Curtis, FAIA, My Life in Modern Architecture and The Rivergate.” University of New Orleans.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.