I Heart Louisiana founder Katrina Brees with her bicycle-powered unicorn

Strange and wonderful creatures populate the hallway outside Katrina Brees’s studio in the Bywater Art Lofts.

“We just finished the nutria,” says Brees, pointing to a three-wheeled bike bearing a giant pointy rodent head and tail. It is one of an array of exotic wheeled species that Brees and cohorts have engineered for street travel for use by the Krewe of AWE in the Tucks parade this Saturday.

The art bikes are the largest of an array of Carnival creations engineered by this Boston transplant. In her 12 years in New Orleans, Brees has embraced all things NOLA. And launched a few, too, including the all-female, all-inclusive Bearded Oysters (her title is Mother Shucker), the parade performance troupe Krewe of Kolossos (catch them in Muses on Wednesday or Tucks on Saturday) and I Heart Louisiana, her most recent endeavor that creates local throws for Carnival krewes.

“I’d never been to New Orleans, and it wasn’t what I thought it would be from the popular media,” says Brees, who arrived here pre-Katrina with a musician friend on the band’s tour bus. (Her current name was chosen post-hurricane.) “New Orleans was a revelation. It was like discovering something new every day.”

Her first foray into the city’s costume mentality came with an invitation to the MoMS Ball. She came up with a bead-bedecked Mardi Bra for the occasion, and has since trademarked the cone-shaped bead-adorned apparel.

“People wanted them at once. It was like a feeding frenzy.”

A Pelican cycle at Brees’s Bywater studio

But for an artist who calls her wearables “trashion” – for the found objects she incorporates into her eco-clothing – the whole concept of plastic beads soon became an issue.

“One day I opened a bag of beads and inside there was a chunk of black, silky hair,” Brees says. “It was so horrifying, and it made me realize there’s a dark side to plastic Mardi Gras beads. It wasn’t just about fun, and it wasn’t a New Orleans thing. It was an industry using cheap foreign labor with obvious dangers to those people.”

The documentary “Mardi Gras Made in China,” which follows Mardi Gras beads from their origin in a Chinese factory to the streets of New Orleans, sealed Brees’s disillusionment with out-sourced Carnival trinkets. For her, she says, beads became joyless, “a symbol of the way we have moved our slavery abroad.”

“I felt they were a distraction from the real beauty that was happening here, the ritual and the community and the way we value art.”

It wasn’t until later that Brees learned that her aesthetic aversion had a parallel in environmental concerns. Plastic beads, she says, can contain all sorts of impurities, from e-waste from melted electronics to carcinogens. She quotes a study by the Ann Arbor Ecology Center that tested random Mardi Gras beads and found either lead, arsenic or cadmium in 80 percent of them.

“After the BP oil spill, I thought, this is ridiculous. We’re about to go to Carnival and we’re going to throw petro-chemicals all over the crowd.”

Brees says that, according to VerdiGras, an organization dedicated to keeping Carnival green, krewe riders toss an average of $56,000 worth of beads per block during parades. While some beads are recycled through organizations like the Arc of Greater New Orleans and the Green Project, most of that eventually winds up in landfills.

A real pearl can be found in the I Heart Louisiana oyster-shell necklace

So Brees decided to attack the problem at its source: krewes and throws. In 2012, she called a gathering of friends and interested parties to a Greening the Gras Conference, and began brainstorming ways to make Carnival throws eco-friendly and local. Not everyone readily jumped on the bandwagon.

“There was a guy from City Hall there, and he said everyone was afraid it would all be macaroni necklaces,” Brees says with a laugh.

It’s not, by any stretch of the imagination. Brees’s I Heart Louisiana purveys an array of imaginative necklaces, magnets, rings, snacks and the like, all made by regional artists and culinary companies.

“The first thing we came up with were snacks,” Brees says. “Food is a deeply cultural thing here, and the state is filled with food manufacturers.”

So I Heart Louisiana began offering small, tossable packets of PJ’s coffee, Aunt Sally’s pralines, Elmer’s candy and Zydeco bars.

“In fact, we originally were going to be A Taste of Louisiana, and offer just food. But we realized that we needed a place for more than just food – a place where any artisan objects could be turned into throws.”

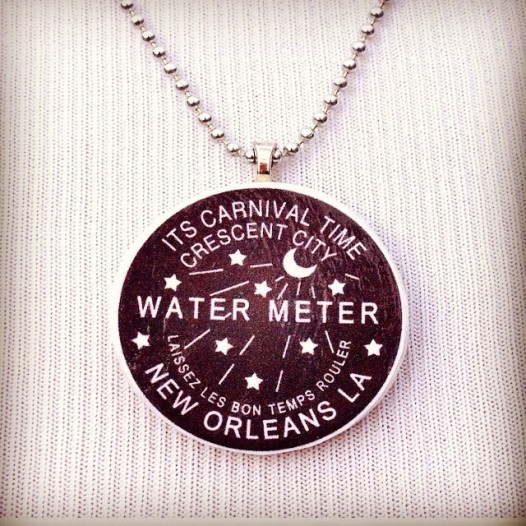

Water meter and other local icons adorn eco-friendly throws.

As a creative type herself, Brees also knows that artists don’t make the best manufacturers. “We would need to assist artists with production.”

At first, Brees and her crew thought they’d need to make throws for 50 cents apiece or less, in order to attract buyers. But when they began interviewing riders, they discovered that those who spend more than $1,000 on throws generally fork out the most for products that cost between $1 and $20 per item.

“Society seems to think throws are cheap, but $1 billion is spent annually on Mardi Gras beads,” Brees says.

Some riders want alternatives to beads to be, well, beads, For them, I Heart Louisiana offers necklaces adorned with the NOLA water meter symbol or krewe logos. A chain holding an oyster shell adorned with a real pearl runs $4. The company’s first customer was the Krewe of Boo, and Brees spent an inordinate amount of time making samples to show them.

“We put almost 100 items in front of the Krewe of Boo before we found ones that they like,” Brees says. The most important consideration isn’t price but heft – no ones wants to toss paper to the crowds.

“And there’s always what we call the ‘crow brain’,” Brees adds. “Whatever shiny object that makes you turn your head and covet it, whether glittered or blinky lights.”

Riders also gravitate to things small enough to store in limited float space, and anything that carries the krewe name on it. For the Krewe of Freret this year, I Heart Louisiana made 1,000 medallion necklaces made of recycled clay with the krewe logo on it.

Those items are often made craft-style, in house. Brees has looked into turning a local warehouse into a factory for throw-manufacturing, but admits that “all that aluminum wasn’t as cute as I thought.”

In fact, mass production isn’t that appealing to an artist who would rather spend hours creating giant papier mache creatures.

“I Heart Louisiana wasn’t created to make money as much as to solve a problem that was hurting me as an artist,” Brees says. This year, the company didn’t solicit business, but had all it could handle. Still, the I Heart Louisiana founder realizes that it’s important to push the movement forward.

“I really want to be the voice for it. I want people to rethink the throw.”

As an artist, Brees gets excited about the creative end of Carnival throw design.

“I want to be the Mignon Faget of Mardi Gras throws,” she says with a laugh. “I’d love to get to design things that are meaningful to New Orleanians, something that ends up in your jewelry box and not a landfill.”

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.