![]() On Saturday morning, a group of peacemakers will gather at St. Roch cemetery in St. Roch, their message one of hope and unity in a world that too often is the opposite. For organizers of the Icons for Peace Walk that will precede the annual New Orleans Sacred Music Festival at The New Orleans Healing Center, it’s all part of a program designed to turn fellow residents into positive, productive people.

On Saturday morning, a group of peacemakers will gather at St. Roch cemetery in St. Roch, their message one of hope and unity in a world that too often is the opposite. For organizers of the Icons for Peace Walk that will precede the annual New Orleans Sacred Music Festival at The New Orleans Healing Center, it’s all part of a program designed to turn fellow residents into positive, productive people.

Icons for Peace was created six months ago, shortly after the first New Orleans Interfaith Peace Games. The event was modeled after a similar one in Chicago that takes gang members off the streets and puts them on the basketball court, where they can work out differences in a more peaceful manner.

The idea of young people as peacemakers appealed to organizers of Icons for Peace, and the movement has been gaining momentum ever since. The program, which operates under the auspices of The Isaiah Institute of New Orleans, an interfaith organization devoted to building community, focuses on a positive rather than negative mindset.

“Fear and violence. Two things we can all agree on,” says Icons for Peace board member John Johnson of NOLA’s urban woes. “Icons for Peace was born out of seeing a need for cohesion in this city.”

“Everything we stress is about positive over negative,” agrees John Lewis, an executive board member of Icons for Peace who also works with Heart of JustUS, a group that provides art supplies to inner-city artists.

Both men salute the many programs devoted to the city’s disenfranchised youth, from after-school sports to the mayor’s NOLA for Life. But they also believe that positive urban change is a product of collective, creative thinking, rather than just individual approaches. For them, Icons for Peace is about connecting the dots. Its multifold mission is to start conversations about peace, support organizations and activities that educate and reward peace, and create leaders who themselves — no matter their backgrounds or standing — become icons of peace themselves.

“Our concept is to bring people together, no matter what they are doing differently,” Johnson explains. “We can come together from a unified front for peace.”

The idea is well suited to New Orleans, they say, because it’s a place where the idea of community is strong. Where people do tend to care for one another, and population diversity – in close geographical quarters — is the norm.

“There’s more to us as New Orleanians than partying or violence,” says Johnson.

But neighborhood in New Orleans can also impact negatively: Unlike those in other metropolitan areas, gangs here are not imported, but tend to form from neighborhood associations with peers. And bad behavior is all too tempting in a society inundated with negative messages, in video games, TV commercials, hip hop music.

His generation, says Lewis, who is 22, also is the first to live in a digital culture that can be socially isolating. “It makes for a segmented population instead of a connected one.”

Combine this kind of adolescent disenfranchisement with an adult population that too often prefers not to get involved with controversy, and you’ve got a recipe for urban strife.

All too often “there’s a lack of interconnectivity” among local residents, explains Johnson. “People aren’t taking care of their neighbors. It’s a doctrine of separation – we don’t want to get involved in others’ problems. And that way we become part of the problem. You can’t sit on the fence.”

Rather than censoring bad behavior, however, Icons for Peace hopes to instill good behavior. Currently, the 6-month-old program has 40 active leaders from all walks of life.

A related program, the New Orleans Peace League, hosts a weekly Saturday morning basketball game at St. Alphonsus School, where kids are invited off the streets and onto the courts.

“Basketball gives them a hook,” Johnson says. “At these games they’re taught anger management and conflict resolution. And out of that always rises a leader. And that leader can make the transition to become an icon of peace.”

Icons for Peace meets with local youth every Tuesday at a Gentilly church. The group also offers talks, support and expertise about peace initiatives to any group that requests it. They do workshops, train leaders, show movies.

“It’s hard to get into an argument with somebody when the word peace is used,” Johnson points out. “Too often, people focus on the parts of their identity that set them apart, that don’t bring them together. If I’m African-American, then I might concentrate more on being African than American. We’re a melting pot but he haven’t melded.

“You know, foreigners who come to America often do well here because they embrace their citizenship. That’s why those populations thrive. So I tell kids that pride in country is the smart option.”

“Part of what we’re doing is working to make people come together as Americans,” Lewis explains.

So a core value of Icons for Peace is patriotism, belief in country, with lessons drawn from the founding fathers. Johnson and Lewis teach the Constitution, emphasizing phrases that few of these kids have studied. In the 13th amendment, for example, they point out that it reads that neither slavery nor servitude shall exist “except as a punishment for crime.” That, they tell kids, means that becoming a criminal in effect makes them 21st century slaves.

Hard words. But necessary ones.

“Felony disenfranchisement is so strong,” Lewis says of kids who fall into into the penal system. “We tell kids, no one is going to let a slave go. You can’t get a passport, you can’t vote, you can’t work.”

“The only way to get out, once you’re in the system, is to do good, so that a good person can vouch for you,” agrees Johnson. “That’s where being a peacemaker comes in. If you can show that you are an American, a peacemaker, that you are willing to do good, you can change things. But it takes you being connected to peacemakers.”

At its most fundamental, Icons for Peace seeks to create connections and form relationships. Good ones. Its supporters talk about the crime culture as a “force multiplier” – that is, when crime is rampant, the environment is conducive to creating more crime. The stimulation to commit crime is there; the mindset to commit crime is there.

“When parents can’t control a child, they kick him out. And that adds to the force multiplier,” says Lewis. “The first thing we tell kids is that they don’t have to buy into what others around them are doing.

“The young people we’re talking to, talking about peace is a new dialogue for them. We give them the analogy of a wall of bricks. Everyone has a brick. Most of them want to throw their brick through a window. We suggest you use your brick to build a wall. And if we do need to break a window, let’s do it together.”

It’s a pronoun choice: “we,” instead of “us” or ”them,” on both sides of the socio-economic divide: “If it’s our country, then we can make it better.”

And Icons for Peace hopes to teach the teachers, too – to give leaders of local programs addressing similar issues a model to deal with those issues. So that a variety of programs can come together to take up shared causes.

“When people from all walks of life start a dialogue, they realize they’re not that different from one another,” Johnson says. “And peace is the anchoring concept for that realization.”

Still, Icons for Peace has concrete objectives beyond starting conversations. The group’s biggest concern is to engage mentors and find jobs for New Orleans’ young people.

“Safety is the big issue,” Johnson says. “You can’t get safety just through policing kids. We have the highest incarceration rate in the world. It takes more.”

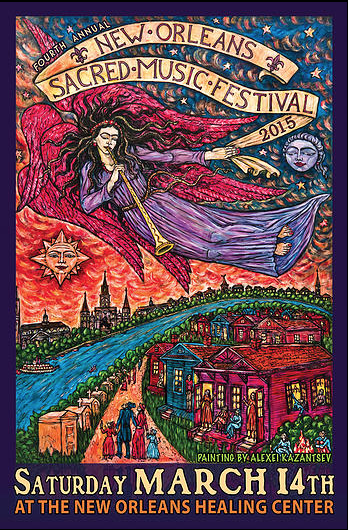

New Orleans Sacred Music Festival

New Orleans Sacred Music Festival

Icons for Peace

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.