Editor’s Note: New Orleans is a city that is considered to be one of the top tourist destinations in the United States, receiving almost 20 million tourists a year. One of those reasons is the unique architectural styles found throughout the city, such as French influence and shotgun homes. Another is the unique style of city planning that began in Jackson square and follows the form of the Mississippi River. The history of the unique architectural styles is something New Orleans natives and those who visit should be informed on — everything from street tiles to not-so-tall buildings. This piece on Audubon Park was originally published on November 23, 2017.

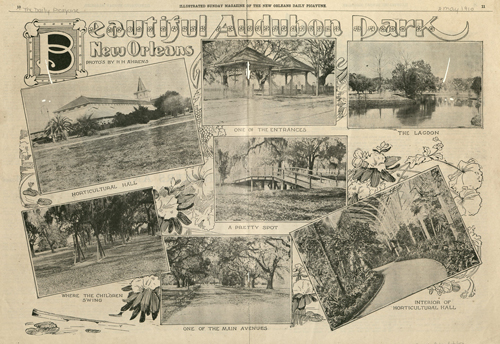

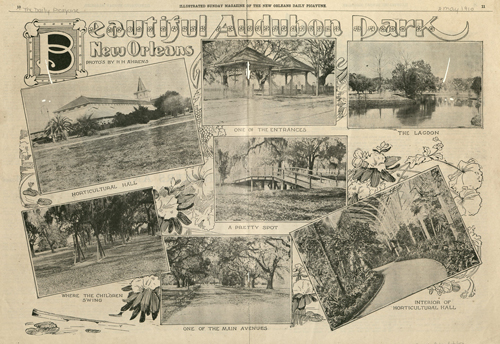

New Orleans Daily Picayune Audubon Photo Spread. Photo by HH Auden from the Ephemera Collection at the Louisiana Research Center.

In the Uptown section of New Orleans, Louisiana, sandwiched between St. Charles Avenue and the Mississippi River, is the lush urban oasis- Audubon Park, named after naturalist John James Audubon. The park borders Audubon Place and is across the street from both Tulane University and Loyola University.

The park is used for recreation of all kinds, including but not limited to: horseback riding, tennis, running, biking, golf, picnics, charity events, and wildlife preservation. Before and after the plot of land was purchased by the city in 1871, it was the site of many historical events and it underwent numerous changes.

The Beginning

The site of Audubon Park today was once a twelve and one-half arpent plantation bought and owned by Pierre Foucher. Foucher abandoned his plantation before the Civil War and fled to France, never returning to Louisiana. The abandoned plantation was used by both the Confederate and Union sides during the war. It was used as a campground for Confederate troops and as a site for a Union military hospital that existed for five years. For almost a decade following, the eyesore of a plot was sold back and forth between wealthy citizens, legislators, and park commission boards. The city of New Orleans purchased the park in 1871. The Upper City Park (the original name of the park) Commission was established in 1879, however the only financial assistance given for operating a park on the site came in the form of revenue from leasing the grounds for grazing (Wilson, Samuel, Mary Louise Christovich, and Roulhac Toledano. New Orleans Architecture. Gretna [La.: Pelican Pub., 1971. Print).

Horticulture Hall

Exterior and Interior of Horticulture Hall. Photos by HH Auden from the Ephemera Collection at the Louisiana Research Center.

The Horticulture Hall (pictured above) exhibited plants from around the world allowing the public to view and learn about exotic plants, as well as eat the fruits that come from them. It contained galleries displaying paintings from Belgium, Mexico, Europe, and America and a Statuary Hall. The Hall was created around 1884 for the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition. It was 600 feet by 19 feet and stood over 90 feet tall. It was made of glass and wood and was the only permanent building of the Cotton Centennial Exposition. However, it was destroyed by the hurricane of 1915 and was never rebuilt (“Horticultural Hall & Art Hall.” Omeka RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 01 Dec. 2014. “Horticultural Hall.” Omeka RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 01 Dec. 2014. “NOPL: Images of the Month—Part 1.” NOPL: Images of the Month—Part 1. N.p., n.d. Web. 01 Dec. 2014).

Early Development

The early history of the park’s development begins with the site being chosen for the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition of 1884-85, which planned to show off the “New South.” The Exposition caused an influx of the population, which contributed immensely to the subsequent development of the park. Although the event was a financial disaster, the positive impact of the fair on the park and its surrounding bourgeois neighborhoods continued for years after. The only known remnant of the the Exposition today is the meteorite, a massive piece of iron ore left over. The New Orleans City Council created a new park commission with a 25-member board to operate the park in May 1886. The name of the park was soon changed to Audubon Park, “after the naturalist-painter, John James Audubon.” Two years later, a ten-year lease was signed for a fifty-acre tract near the river to be used as an important sugar experimentation station by the Louisiana Science and Agriculture Association. The station was closed in the 1920’s, and the plot “became the site of the swimming pool, tennis courts, and a portion of the zoo” (Wilson, Samuel, Mary Louise Christovich, and Roulhac Toledano. New Orleans Architecture. Gretna [La.: Pelican Pub., 1971. Print).

Swimming Pool at Audubon Park. Photo by HH Auden from the Ephemera Collection at the Louisiana Research Center.

Plans and Progress

In 1900, “the initial phase of the park began.” John Charles Olmsted was hired as the park’s designer and completed a master plan in 1898 whose implementation took another twenty years, mainly due to a lack of money. Some delays caused by the board included the leasing of the park’s riverfront to The Corps of Engineers and the constructing of railroad tracks along a new levee of the river by the Illinois Central Railroad, detracting from Olmsted’s “grand riverfront promenade”(Times-Picayune, The. “1898: Audubon Park Is Transformed in Uptown New Orleans | NOLA.com.” New Orleans, LA Local News, Breaking News, Sports & Weather – NOLA.com. Web. 04 Dec. 2011). The board also allowed concessions (such as one for a miniature train), extended the lease of the sugar experimentation station, and granted Olmsted’s meadow to the Audubon Golf Club, a long-standing addition that has maintained golf as a prominent activity in the park since 1898. Soon, a carousel, a polo club, and the Audubon Tea Room were added. As board presidents passed away and new ones took over, much of the original Olmstedian design was compromised in order to evolve the neighborhood park into a park where “people from varied backgrounds wanted to come for recreational pursuits.” Such compromises included the addition of various structures for active recreation such as swimming, tennis, and softball. Most of these were financed by private donors as memorials. Numerous memorials erected during this time (1916-1920s) still stand in the park today. These include Moise Goldstein’s neoclassical St. Charles Avenue entrance, the numerous gazebos, Emile Weil’s Newman Band Stand, the Gumbel Fountain, the Hyams wading pool, and the Popp floral gardens (Wilson, Samuel, Mary Louise Christovich, and Roulhac Toledano. New Orleans Architecture. Gretna [La.: Pelican Pub., 1971. Print).

Gumbel Fountain. Photo by HH Auden from the Ephemera Collection at the Louisiana Research Center.

Hymas Wading Pool. Photo by HH Auden from the Ephemera Collection at the Louisiana Research Center.

Popp Garden. Photo by HH Auden from the Ephemera Collection at the Louisiana Research Center.

Audubon Zoo

Contrary to memories of the zoo in the past, a trip to the zoo today is a pleasant and educational experience. In the past, the zoo featured disagreeable images, such as “scratching, caged animals, steamy, unshaded paved walks, foul smells ripening in the heat, and a moth-eaten stuffed bear.” The beginning of the zoo was simultaneous with the implementation of the Olmsted Park plans. Massive remodeling in the 1970s turned it into the “spacious, airy landscape” of today filled with an enormous variety of animal species and exhibits.

Elephant House. Photo by HH Auden from the Ephemera Collection at the Louisiana Research Center.

Bird House. Photo by HH Auden from the Ephemera Collection at the Louisiana Research Center.

Sea Lion Pool. Photo by HH Auden from the Ephemera Collection at the Louisiana Research Center.

Audubon Golf Course

New Orleans’ Golf Course, located in uptown, scenic Audubon Park is one of the most renowned courses today. It was awarded a four and a half out of five stars in Golf’s Digests’ “Best Places to Play” article, ranking golf courses across the country (“Audubon Park Golf Course.” Audubon Golf Course, Golf Now. 2002. website). However, something setting this course apart is its historic significance. On the current grounds of the 18-hole course lies the history and memories of the 1884 World’s Fair. This fair was home to traders and businessmen exploring the unique city of New Orleans. Due to the fact that one third of the cotton industry was produced in the city; it attracted many of these business oriented tourists. The United States Congress lent $1 million to the fair’s directors and gave them $300,000 for construction of on-site exhibits. It is because of this that the Golf Course was able to open in 1898, along with the Audubon Zoo (“Audubon Park Golf Course Www.auduboninstitute.org.” New Orleans Tourism Marketing Corporation. 1996-2014. website).

In 2002, the course underwent a $6 million renovation, improving the difficult 4,220-yard greens. Architect Denis Griffiths designed the complicated 12 par 3s, four par 4s, and two par 5s layout. (“Audubon Park Golf Course Www.auduboninstitute.org.” New Orleans Tourism Marketing Corporation. 1996-2014. website). The famous architect also designed well known courses in England, Spain, South Africa, Japan, Thailand, and Scotland (“American Society of Golf Course Architects.” Member Profile. 2013). Today, the course hosts several tournaments and on-site golf events, bringing in high revenue and income for the Park’s regulators. Including the infamous Saturday Series of the PGA Tour in 2002. The professional business of the golf course includes a Clubhouse and café where events such as weddings and parties can be hosted as well (“Tournaments.” Audubon Nature Institute. 2014. Association of Zoos and Aquariums).

A Glimpse at the Park in the Year 1924

In the year 1924, the park’s visitors numbered over a million each year. In 1924, Dr. William Scheppegrell was the president of the Audubon Park Commission, and the Vice President was J.K. Newman. The commission consisted of seven standing committees: executive, finance, amusements, grounds, donations and requests, concessions and leases, and zoo and aquarium. Since the year 1919, a variety of developments have been made that show great strides in popularity and in attendance to the park. Such developments included “more tennis courts, baseball diamonds, and fields for football,” and other sports. The ultimate improvements responsible for the influx of popularity were the developments made to the Audubon Zoo and Odenheimer Aquarium, which at this time was home to over 1,000 birds, reptiles, mammals, and fish. During this period of time, band concerts and “moving pictures” were available each summer season at the Newman Memorial Band Stand. Concerning the sugar experiment station, the land occupied by it was recovered to the park this year, and the creation of a baseball field was the first step taken “to meet the growing demand of the Park for recreational purposes” (Scheppegrell, William A., Marion Weis, and Harold J. Neale, eds. Glimpses of Audubon Parl. 3rd ed. New Orleans: Audubon Park Commission, 1924. Print).

New Orleans native Mary Lou Widmer recalled her childhood outings to the park during the depression years. “A day was set aside, the family was collected, and the long ride began. Our old car wove in and out of those unfamiliar uptown streets, loaded with kids, a picnic lunch and our cooler full of root beer…What a pool Audubon Park had!…The bathhouse was a wonder in itself. I remember the endless row of lockerds, the changing booths, and the huge, mirrored room with hairdryers in the wall. I loved the various facilities. I enjoyed changing my clothes in a private booth, wearing my jingling locker key pinned to the belt of my bathing suit, and running through the hallway of shower jets that sprayed me just before I entering the revolving door-way to the pool. These were all spiffy new things we did not have at the City Park pool” (Wilson, Samuel, Mary Louise Christovich, and Roulhac Toledano. New Orleans Architecture. Gretna [La.: Pelican Pub., 1971. Print).

Up to Present Day

Today, the park continues to thrive, as it has for over a century, as a mecca for outdoor recreation of every kind. People continue to visit the Park to take full advantage of “the alleys of ancient live oaks, the tranquil 1.8 mile jogging path, the lagoon, picnic shelters, playgrounds, tennis courts and soccer fields. Audubon Park remains open to the public and also features Audubon Clubhouse Café and Audubon Golf Club, which is still a premier public Golf Course.” (“Audubon Park | Audubon Nature Institute.” Audubon Nature Institute | Celebrating the Wonders of Nature. Web. 04 Dec. 2011).

The park has been the site of numerous cancer walks, charity events, golf tournaments, and various fundraisers (“Walk through Audubon Park Saturday Will Help Fight MS | NOLA.com.” New Orleans, LA Local News, Breaking News, Sports & Weather – NOLA.com. Web. 04 Dec. 2011).

One such modern amenity of Audubon Park are the The Cascade Stables, which were established in 1983 when the family of Barbara Smith revived the former Audubon Stables, restoring the 3 acre equestrian facility which today sits on to the east of Audubon Zoo, and just south of Magazine Street (Audubon Park trots out plans for stables – Old wood barn razed last month Times-Picayune, The (New Orleans, LA) – March 9, 2005 Author: Bruce Eggler Staff writer Section: METRO Page: 01).

Notable not only for their general equestrian services such as horse riding lessons and rentals, Cascade Stables is “one of the top 20 show stables in the country,” contributing the majority of the horses used in New Orleans’ annual Mardi Gras Parade (“Cascade Stables And The Horses Of Mardi Gras” WWNO. February 24, 2014. Website).

Numerous species can still be found dwelling in the park. However, in the spring of 2011, the park experienced a wildlife phenomenon when the birds of Bird Island, also known as Ochsner Island, left the isle for unknown reasons (“Audubon Park Bird Island Mysteriously Abandoned | NOLA.com.” New Orleans, LA Local News, Breaking News, Sports & Weather – NOLA.com. Web. 04 Dec. 2011).

Improvements and additions continue to be made, such as a meditation area (“Meditation Area Dedicated at Audubon Park | NOLA.com.” Blogs – NOLA.com. Web. 04 Dec. 2011). However, not all citizens favor further developments to the site. In 2001, citizens formed a group called Save Audubon Park. “Save Audubon Park is a grass-roots citizens group formed in reaction to the Audubon Nature Institute’s plans to rebuild and expand the historic Audubon Park Golf Course.” (Barrow, Bill. “Save Audubon Park.” Web. 04 Dec. 2011).