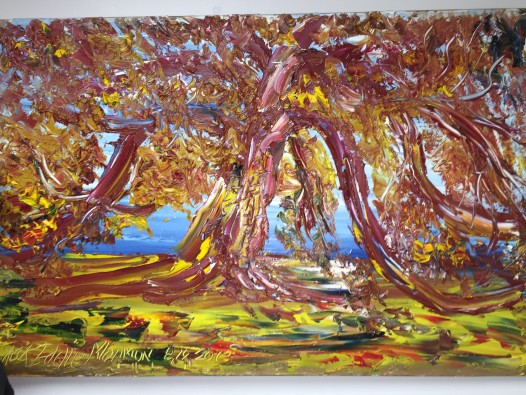

‘Maroon Bells, Aspen,’ by Eddie Mormon (Photo: Gulfbank.com)

Last Wednesday was Rock Eddie Mormon’s birthday, but, as usual with this ebullient self-taught artist who had just turned 62, he wasn’t thinking about himself.

Artist Eddie Mormon (Photo: Renee Peck)

No, the Lake Charles native was squeezing paints onto a floral-patterned paper plate, preparing to demonstrate his lifetime-honed technique of painting with a palette knife by creating a still life of sunflowers. Morning light spattered the windows of the Metairie office of Jefferson Dollars for Scholars, where Mormon had driven the 200 miles from home to deliver a painting that — not surprisingly, if you know Eddie — would go to charity.

That 3×4-foot work, “Maroon Bells, Aspen,” is part of Gulf Coast Bank’s annual Auctions in August, an annual month-long online and onsite auction to benefit local non-profits. And Eddie’s contribution of two works to the cause – the other is a 4×8-foot oil on wood painting called “Moonwalk and Thriller,” painted the day after Michael Jackson died – caps a long relationship with Jefferson Dollars for Scholars.

“I got a call one day from Eddie, who had heard me talking on the radio,” says Lisa Conescu, with Jefferson Dollars for Scholars. “He said he likes to support nonprofits, and he was going to paint something for our gala auction. We started talking, and I discovered that he likes to deliver his paintings personally and come to the event.”

Live Oak, by Eddie Mormon (Photo: Renee Peck)

So he did. And Eddie has painted many things for the organization since. These days, he rarely arrives on his frequent visits to New Orleans without a stop to see Lisa.

“He rents a Budget truck and drives to town, and then whips open the back and you can’t believe the things in it,” Lisa says.

On any given trek, Eddie carries an array of the exuberant, brightly colored oil landscapes and still lifes for which he is known, as well as prints, posters and calendars – he has several dedicated collectors in town, and his Abita beer portraits are sold at the brewery on the north shore.

And, of course, he brings lots of good stories: Eddie is a born raconteur.

“I was drawing in the dirt when I was 5 years old,” he says. “As a little boy coming up I’d paint with oils in my mama’s house. One day I messed up the table and she threw all the paints outside. My grandmama told her, you never know what he’ll grow up to be.” So his mama let him paint.

Roses, by Eddie Mormon (Photo: Renee Peck)

One of six children – there’s some Blackfoot Indian on his dad’s side – Eddie grew up hard and poor in an era when, he said, “nothing came to us easy. I learned that we have to make what we have in life. And that life is good to you if you’re good.”

Through high school, he continued his painting, placing second in a statewide art contest in Baton Rouge. After graduation, he headed to a cousin’s house in Colorado with hopes of attending the Colorado Institute of Art. His first view of the Rockies, he recalls, inspired him.

“The Colorado mountains are one of the most beautiful sights in the world. They change color like a rainbow.”

Eddie returned to Louisiana in 1974, where he followed his father to the Lake Charles waterfront as a stevedore. For the next two decades, he worked to support his wife, Monica, and their three daughters. When a dockside injury sidelined him permanently in 1993, he returned to his art.

“I paint from a feeling that comes from my soul,” he says of his work. “I see it in my mind, whole.”

Still, he likes to sketch – he’s never without a Sharpie or two in his pocket and a pad at his side – and often does what he calls “preambles” for works that are commissioned. But his trademark, he says, is the way he paints from inside: “I see it and it comes out just as I see it.”

Eddie Mormon paints exuberantly (Photo: Renee Peck)

Eddie is not stingy with his paint. He lays out fat curls of lemon yellow and cerulean blue and crimson, then swirls them together with the edge of his knife before laying them on the canvas in broad, circular strokes. His oil paintings sometimes take weeks to dry, so thick is the paint layered.

It’s quickly obvious that Eddie never meets a stranger, and can pull instantly from an internal store of favorite quips: “Better catch a ship before it sails.” “Everybody gets a chance in life.” “It’s not how much money you make, but how you live that counts.”

Certain things, he says, just touch him. The Colorado mountains, the Brooklyn Bridge in New York, certain bayou landscapes or historical tales at home.

And New Orleans. “This city touched me in my soul.”

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.