Katie Burke is a writer and family law attorney, who lives in San Francisco. She visits New Orleans annually to write, volunteer, visit friends, and dance to our world class brass music. Her encounters with New Orleans’ fascinating characters gives her a unique view into the soul of our city.

Katie Burke is a writer and family law attorney, who lives in San Francisco. She visits New Orleans annually to write, volunteer, visit friends, and dance to our world class brass music. Her encounters with New Orleans’ fascinating characters gives her a unique view into the soul of our city.

Dooky would die within two weeks, on November 22, at age 88. Leah and her jazz trumpeter husband, Edgar “Dooky” Chase, transformed their establishment in 1946 from a barroom and sandwich shop to the sit-down restaurant it is today.

He shrugged and replied, “I’m all right.”

We held each other’s gaze for an extended moment. With no such words exchanged, we were talking about the presidential election results, and something in his kind smile saddened me.

Photos by: Katie Burke

Shortly thereafter, a black woman in her thirties asked to take my order. The smell of the restaurant’s famous fried chicken tempted me, but I ordered white bean chili soup instead. As I indulged in my flavorful, hearty, and delicious soup, I overheard a white woman in her twenties speaking loudly to her thirty-something white, male companion about her shock and outrage at the election results.

“No, I’m the owner’s daughter. She’s being interviewed right now,” the woman told me of her mother, “but I’ll see if she can meet you after that.”

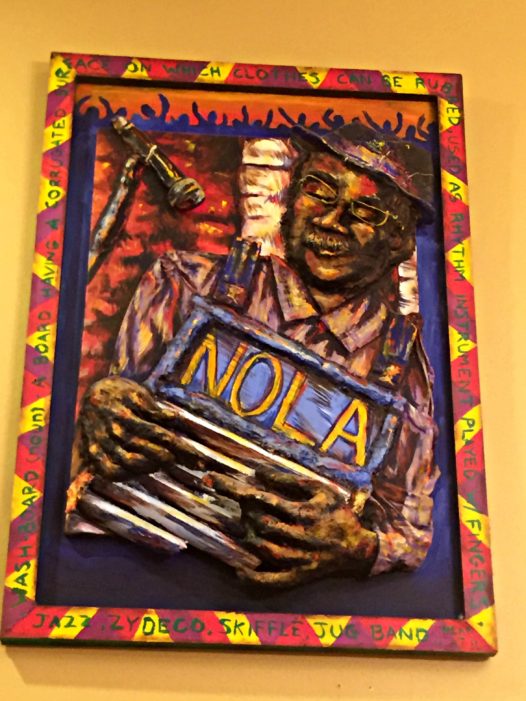

As I waited, my eyes wandered onto the several paintings that covered the walls of the restaurant, a living monument to New Orleans culture and history, prominently featuring members of the black community and including various portraits of jazz performers.

Leah’s daughter led me to another dining room, where Leah smiled brightly upon my arrival, as if I’d earned her delight. We discussed the election and my time in New Orleans. When I asked Leah about the artwork on the walls, she said she buys some of it and that local artists occasionally give her pieces. She pointed to two paintings her granddaughter had made: one, a portrait of Louis Armstrong; and the other, a scene that appears to feature a soldier holding a gun, “but if you look closely, what he’s really holding is a wound, and you can see the blood dripping down from his clothes.”

Leah told me that in addition to being an artist, her granddaughter is a jazz singer, “just like her mother.”

Art work from Dooky Chase’s Restaurant (Photos by: Katie Burke)

When I asked Leah whether the artist’s mother is the woman who’d introduced us, Leah said, “No. Her mother sings jazz all over, and teaches jazz at Tulane, Loyola, and the University of New Orleans. And my granddaughter sings jazz on a cruise ship. But she needs to get done with that and come back home.”

Leah added, “I’m so proud of my children. If you are making your own money and helping others, that’s all a parent can ask for. My children don’t have to do anything for me … and they do, and I appreciate it, but they don’t have to. They are supporting their families and helping everyone around them.”

Leah and I continued speaking for several more minutes. As I rose to leave, an interviewer with multiple professional cameras was waiting to speak with Leah. Leah jumped right in with him as I walked away.

On a day when I felt overwhelming anguish, Leah reminded me that there are great people everywhere, no matter the circumstances, and that the spirit and heart of New Orleans is as rich as Dooky Chase’s white bean chili soup.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.