UNO professor Mary Niall Mitchell (Photo: uno.edu)

New Orleans is a city of stories, stories about individuals, places and happenings that weave a collective tapestry of a rich and colorful past. Students in the history department of the University of New Orleans have been spinning these threads into an innovative website and smart phone app. Recently we sat down with professor Mary Niall Mitchell, New Orleans historian and co-director of the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies, about New Orleans Historical. The project researches stories about the city and makes them available to us to study and, literally, to follow.

What is New Orleans historical and how did it come about?

We have my late colleague Michael Mizell-Nelson to thank for this website. He got it started, working with some friends of his at Cleveland Historical. They designed the software for this program and Michael was an early adopter and a true public historian and had for years tried to find a way to tell the unfamiliar stories about New Orleans. He wanted people to hear these stories; he wasn’t interested in them staying in books and scholarly articles and things like that. He wanted to get the stories out to the public and in an accessible way.

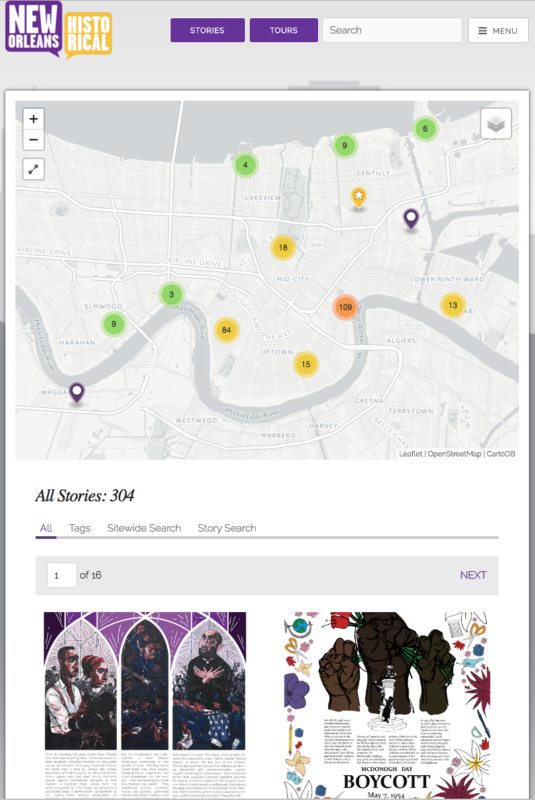

This platform allowed him to get these stories out there. You can download the New Orleans Historical app on your phone; you can also do this from your computer, but I recommend that everybody just put the app on their phones. If you have the location services active, then it will know where you are, it can tell you what sites are around you.

We encourage students to put these places on the map, to put people and places on the landscape of the city, even if they don’t exist anymore or even if people don’t know much about them What I like about it being a site-based app is that the landscape itself is something that people relate to. People use Google maps all the time, right? They’re familiar with navigating digitally these days, and so to be able to put these stories on that map is very exciting and we hope changes the way people think about the city.

(Photo: neworleanshistorical.org)

Your stories run the gamut: You’ve got everything from Danny Barker’s birthplace to The Tango Belt that once operated in the upper French Quarter. You’ve got the My Oh My vintage drag lounge on the lakefront; you’ve got all of the Hurricane Katrina breaches. So how do you and your students determine what you’re going to research and how you’re going to put together your tours?

There are stories that the students have researched collaboratively in class — these are UNO and also Tulane students. We’re hoping to get some other schools involved as well this year. So that’s one way the stories get produced, as part of a class on a given topic. Students will be asked to come up with some sites that they want to do research on, and research those sites. That requires them to go into archives to find out information, but also to find visuals. It may require them to go do oral histories with people who have memories of certain sites.

But we’ve collaborated with other groups as well to get content up on New Orleans Historical. You’ll notice that the Louisiana State Museum comes up a lot; we collaborate with them in terms of their collections. The Katrina tour that you can take is sponsored by levees.org. So we’ve really tried to make this a community effort as much as we can; it’s great for the students to learn how to do these things, but we also want them to learn how to collaborate more broadly and to speak to the community and collaborate with the community institutions and cultural institution.

Sometimes there is a crying need for a tour — say on the 10th anniversary of Katrina, because people are going to be looking for that information. The Confederate monuments would be another example. We had to make sure that our Confederate monument sites were up to date, starting around 2015 when the debates started happening about the monuments. Those kinds of tours are very exciting to work on because it’s really valuable information for the public, for journalists as well.

The digital aspect of this is very cutting edge. The monuments and other tours show us that history is in the present and is taking us into the future as well.

I think people all of a sudden wake up and realize the relevance, the current debates, and how engaged they are with the past. Going forward with the Tricentennial, that’s an exciting prospect. We’re hoping to add a lot more.

I should explain that the site is organized according to stories and tours, so a story is an individual site. You don’t have to take the whole tour from beginning to end; they’re organized so that you can walk them. Sometimes they are driving tours. We do have one very interesting tour about the history of leprosy in Carville, Louisiana, and that came about through a student who did a lot of research on it and collaborated with a local museum curator in Carville . There are streetcar tours that we’re working on.

It’s a location based-application, so each story has a location and a place where that story is anchored, correct?

That’s right. Each story is on a tour, but you don’t have to take the whole tour, you can just drop in and read about that particular story. I think we have about 30 tours all together and within that there are multiple sites.

What are your criteria for telling these stories? Can anyone add them? Is there a curation process?

They really are vetted and that’s what distinguishes New Orleans Historical as a site — they come out of deep research by scholars or students or organizations or museums. If they are written in the context of a course, the professor and the rest of the class vets these stories and make sure that the citations are correct and all of that sort of material to back up the stories is there, including visuals and audio and things like that. And then of course we do have scholars who just want to upload things that they’ve done. So it’s a multi-step process, but it always begins with strong archival research.

(Photo: neworleanshistorical.org)

This is really storytelling, not in an overly academic way, although they are academic and they are sourced and they are footnoted, but also in a way that makes the city’s past come alive. Is this something that New Orleans just adapts well to?

It is perfect for New Orleans. Because we’re so reliant on tourism, it’s very easy to fall back on the same stories, because those stories are pretty lively and people who are visiting from out of town want to hear about Storyville and they want to hear about things like jazz; that’s what they’re expecting. So what’s nice is to be able to offer them something that’s unexpected and that really supports the whole notion of so-called cultural tourism. People are now traveling and wanting to know those unfamiliar stories; they don’t want the tried and true, they want to feel like they’ve gotten the inside scoop on something. And so particularly with New Orleans Historical, the way the stories are put together sometimes in a quirky way, it makes for really lively entertaining reading.

What’s your favorite tour?

I like Animals in the French Quarter. It’s always the one I pull out to talk about when I’m talking about New Orleans Historical. It involves four stops, so it’s mules, rats, mosquitoes and termites. That sounds pretty quirky, right? But what I love about that tour is that it gets to these much larger historical issues in a lively way and in a way that people will remember. So when you read about the mules in the French Quarter and you read about the campaign to improve the condition of mules in the late 19th century, that’s the origins of the Louisiana ASPCA. So you learn about that, you learn about the modernization to the city because eventually the mule goes by the wayside and you get the electric streetcar. So you learn about these larger issues within the city’s history, but in a fun way. The same thing with termites: You learn about historic preservation when you learn about the termite infestation and the battles against that infestation.

What’s out there that you’d like to see some of your students or scholars investigate?

There’s a lot of 20th-century history in New Orleans that people aren’t familiar with. We are more of a colonial city and we talk about the 19th-century history. There is so much fascinating history, especially political history, but other things as well — cultural history, history of gays and lesbians, that doesn’t get covered, or that people are unfamiliar with.

What do you hope that your students get out of this project?

We want them to learn first of all the value of research, but we also want them to learn the value of storytelling and how to be good story tellers, how to reach an audience and not lose them. If you’re writing up your research and you’re trained in a certain way as a scholar, it’s not that easy to keep a broad audience. So we want students to learn how to translate the skills that they’ve acquitted at university into a writing style that is engaging, that is clear, that is exciting for people to read and that serves a real public purpose.

It’s also preservation in its purest sense, because things may not last in real time but in virtual time we can preserve them.

What’s lovely about the digital medium is that it’s never over. That can be a burden in some ways, because you constantly have to keep it updated and you have to stay on top of it. It’s not a like a book you can put on a shelf and walk away from. But the flip side of that is that there’re always things that can be added. It’s constantly being revised.

Those who are looking for a one-of-a-kind tour of New Orleans or who want to read stories about the city’s lesser-known people, places or events can head to neworleanshistorical.org. In anticipation of the city’s Tricentennial celebration in 2018, ViaNolaVie and New Orleans Historical will be bringing you a monthly feature about one of the site’s city tours. So stay tuned for upcoming pieces on tours that may teach you about animals in the French Quarter or gambling in Jefferson or even that driving tour to the former on leprosarium in Carville.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.