Editor’s Note: According to a History of New Orleans Voodoo, “The core belief of New Orleans Voodoo is that one God does not interfere in daily lives, but that spirits do. Connection with these spirits can be obtained through various rituals such as dance, music, chanting, and snakes,” and in this way the mystery associated with New Orleans begins to materialize. However, it is important to know the truth behind these myths in order to honor the history of the city and to adequately move in the right direction in the fight for social and environmental justice. From its history and culture, all the way to its arts and food, the tourism industry in New Orleans has perpetuated a vast array of myths which continue to exploit the city. Yet, while New Orleans is so popular and well known, the question remains: how much of what people know is actually true, and how does this impact the city? Through exploring New Orleans’ Senegalese roots, highlighting its Honduran connections, and uncovering the origins of hip hop, the following articles provide a keen insight into the various ways the tourism industry in New Orleans continues to spread disinformation for monetary gain. This piece on burials was originally published on September 5, 2017.

Visitors are often are drawn to New Orleans by the fresh oysters and famous above the ground graves that are embedded in the city’s historical past. Most people listen to empty shells to hear the sounds of the wild and free ocean echoing through the shell’s scintillating striations.But for many enslaved Africans living in America, seashells were the symbols of immortality and water, and a way to guide the deceased to afterlife – and thus taking them back home.

Oyster Shell found in New Orleans on a grave in Lafayette Cemetery. Photo by Monika Kozicz.

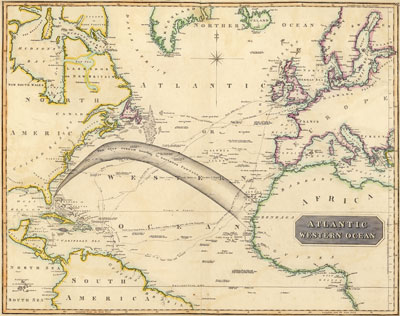

Most visitors are aware of the influences that slave trade had in Louisiana and New Orleans. But what many visitors don’t know is that the majority of the slave force in Louisiana traveled through the Atlantic from Senegambia. The Louisiana Slave Database, shows that the vast majority of the slaves whose birthplaces were identified were Africans. The database shows that among 38,019 slaves whose birthplaces were recorded, 24,349 (64 percent) were of African birth. Two-thirds of slaves arriving in Louisiana were from Senegambia, mostly Bambara people from present day Mali, and Wolof’s located at the mouth of the Senegal River (Hall, 34-40).

So even though for most people, New Orleans and Senegal seem like two worlds apart, the fact is that New Orleans culture has been extremely influenced by Senegalese culture due to the vast amount of slaves brought through the ports of the Mississippi river. And so the slow but gradual process of creolization arose.

Map, Atlantic Ocean, 1815 as found on www.slaveryimages.org, Robert Sayer, Atlantic or Western Ocean, Copy in the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University. – Showing the route that the slaves traveled.

Creolization is a term that is often linked to the south, disregarding the true meaning of the word. Creolization means more than just mixture; it involves the creation of new cultures. New cultures created through a negative context, like the take-over of others in situations of physical invasion and conquest. It is a “process of assimilation in which neighboring cultures share certain features to form a new distinct culture.” This process is a gradual and automatic response when different cultures mix and influence one and another.

In New Orleans, ceremonial culture has been influenced by Senegal in many ways: like the food, the music, religion and ceremonial and festive culture. The story of the seashell is part of the traces that were brought here by senegalese burial rituals. Funeral customs were one of the few areas of Black life into which slave owners tended not to intrude. So many of the former rituals associated with the respect of the dead were retained. One of these rituals was the custom of placing personal items on graves is more than an emotional gesture. In addition to personal objects, some African-American graves in the South are decorated with white seashells and pebbles, suggesting the watering environment at the bottom of either the ocean or a lake or river.

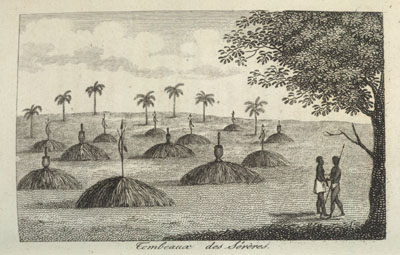

White seashells, were symbols of immortality and water. The spirit domain was metaphorically located beneath bodies of water guiding the deceased to afterlife(King, 128). The main influences of Senegalese burial rituals were by the Serer. The Serer people had very specific burial rituals. They used a type of stone called Laterite and Magaliths that they carved in and placed in a circle, while they directed the stones towards the east.

These stone circles can only been found in the ancient Serer Kingdom of Saloum. Aside from the Stone Circles, they also built large sand tombs and still continue to build them until this day. One of the most characteristic features of the mounds and graves were the shells found on top of the graves. According to “The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, Volume 23, Folk Art” by Crown, Rivers and Wilson, seashells were seen as the representation of slaves returning to Africa: “They said the sea had brought them to their new country and the sea would return them to Africa when they died.” The seashells “create an image of a river bottom, the environment in African belief under which the realm of the dead is located” (Vlach, 143). Some gravesites were outlined with seashells, others were entirely covered. Shells were also used to create designs and decorations.

Whether the shells in the south are found scattered on top of the graves or cemented in place “they are meant as a symbol that ensures a safe journey is made to that unknown shore where everlasting life is possible. Loose shells placed on a tombstone or dropped on the ground around it are also a visible reminder that the person buried below continues to be remembered and honored by those still living.”

More interestingly, The African World Heritage Sites describe the discovery of two hundred eighteen man-made shell mounds in the Saloum Delta. The Saloum Delta lies about 100 km south of the Senegalese capital, Dakar. Some 28 of these mounds have been found to include burial tumuli containing some remarkable artifacts. Over the centuries these mounds have formed interesting islands that now play an important role in the stabilization of the Delta land’s channels.

Cemetery, Senegambia, 1780s as seen on www.slaveryimages.org, René Claude Geoffroy de Villeneuve, Copy in Special Collections, University of Virginia Library. – Showing Senegalese burial ceremonies placing objects on top of the above the ground built burial huts.

These shell mounds form typical cultural landscapes and the mounds that function as tumuli form funerary sites. The shell mound burial rituals and the megaliths tumuli culture. The Serer, Wolof and Mande speakers are thought to have practiced these tumuli burials until the 16th and 17th century. But the Serer continued to practice these rituals in more recent historical periods.

These practices have been described by 19th century sources as “When a person dies, his body is carried to the cemetery and places on a bed of shells under a straw hut, which is then covered with shells: these are tumuli of the shells of Osyters or Arca… When a relative dies, the tumulus is opened in order to place the body alongside those who preceded the deceased in death., then the opening is resealed. Offerings of millet and milk are made to the dead” (Becker and Martin, 266-7).

New Orleans City Cemetery. Photo by Monika Kozicz – Showing the above the ground graves.

New Orleans is famous for their above the ground tombs. Experience New Orleans describes how the these tombs were developed: “At the time, Esteban Miro was the governor of New Orleans, and his allegiance was to Spain. Therefore, when the St. Louis Cemetery was developed, the wall vault system that was popular in Spain at the time was adopted for those who wished to be buried stylishly above ground. Ground burial also continued at St. Louis Cemetery.”

New Orleans Cemetery, shells scattered on top of a grave. Photo by Monika Kozicz

Shortly after, epidemics ruled over the city of New Orleans in the early 1830s. A lot of people blamed these epidemics on the rotting fumes emitted by corpses. So in order to control the epidemics the city council passed an ordinance requiring all further burials to take place on land purchased on the Bayou St. John. And all burials could “continue at the existing cemeteries if they were in tombs and vaults in existing above ground structures.” This is how the above the ground graves became part of New Orleans’ burial culture. Visitors walking through the cemeteries of New Orleans, can not miss these above the ground graves. But even more noticeably, a lot of the graves are covered with shells, telling a story of ceremonial culture and creolization. The shells are often spread on top of the graves resembling the burial rituals of the Serer people in the 19th century.

Burials are private affairs, that are not advertised nor talked about, thus it is hard to trace the exact path of the symbolic shells decorating the graveyards of New Orleans. It is a challenging journey to prove that the seashells in New Orleans graves are a result of the influences of the Atlantic Slave Trade. Even thought a lot of seashells are found in cemeteries where white settlers are buried, the seashell decorations can only be found in South. As the majority of slave trade can intrinsically be linked to the south, it can be theorized that the traces of shells scattered across the famous cemeteries in New Orleans is a tradition that was taken from West African burial rituals. One thing remains clear: Seashells played a prominent role in representing the transition from this life to the next and created interesting ways to understand the connected and comparative histories and cultures of New Orleans and Senegal.

St Lafayette Cemetery New Orleans, Graves where shells were found. Photo by Monika Kozicz

Above Ground Tombs in New Orleans | Experience New Orleans! N.p., n.d. Web. 04 Apr. 2017.

Available at <http://www.experienceneworleans.com/deadcity1.html>.

Buchtel, Jason R. 1993. Ghost of Stone: A Look at New Orleans’ Unique Cemeteries. Cave Creek

Becker C. and V. Martin, (1982b) “Rites de sepulture pre islamiques au Senegal et vestiges protohistoriques”. Archives Suisses d’Anthropologie Generale, 46, 261-93.

Productions, Inc.,”Burial Styles & Traditions.” Lafayette Cemetery Research Project, New Orleans. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Mar. 2017.

Dupont, Ann. 1996. Ceremonial Textiles, University of Nebraska, Print.

Hall, Gwendolyn. Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in Eighteenth Century Louisiana (Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press, 1995), 34-40.

“Laterite.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 29 Mar. 2017. Web. 04 Apr. 2017. Available at:

<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laterite>. “Megalith.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 03 Apr. 2017. Web. 04 Apr. 2017. Available at:

<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Megalith>.”Mysendoff.com.” Mysendoff.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 04 Apr. 2017. <https://mysendoff.com/2011/07/funeral-traditions-in-senegal/>.Opper, Marie-José and Opper, Howard (1989). “Diakhité: A Study of the Beads from an 18th-19th-Century Burial Site in Senegal, West Africa.” BEADS: Journal of the

Society of Bead Researchers 1: 5-20. Available at: http://surface.syr.edu/beads/vol1/iss1/4 “Pulse of the Planet.” African Ceremonies: Niger, Senegal and Ethiopia : Pulse of the Planet.

N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Mar. 2017. “Saloum Delta – Senegal.” Saloum Delta (Senegal) | African World Heritage Sites. N.p., n.d. Web. 04 Apr. 2017. Available at: <http://www.africanworldheritagesites.org/cultural-places/traditional-cultural-landscapes/saloum-delta.html>

“Serer prehistory.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 31 Mar. 2017. Web. 04 Apr. 2017. Available at <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serer_prehistory>.

Vlach, John Michael. 1990 Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts. University of Georgia Press, Athens.

West Africa During the Atlantic Slave Trade Archaeological Perspectives. N.p.: Bloomsbury USA Academic, 2016. Print.

This article has been edited for content, and you can find the original version here.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.