One of the fun things about Dutch is the way they put words together. Erfgoed is “heritage,” which is literally a yard, an estate, a court, or even a cattle yard + “good” as in thumbs up and a property. Plus erven means “inheritance.” I got to see one of these odd combinations of meanings in action the first week of November when I stumbled into a pop-up lab called Waste No Waste. There, in the city market square among the 17th century buildings, a massive striped warehouse contained weavers, bakers, herders, and farmers. What they were doing was erfgoed.

Photo by Vicki Mayer.

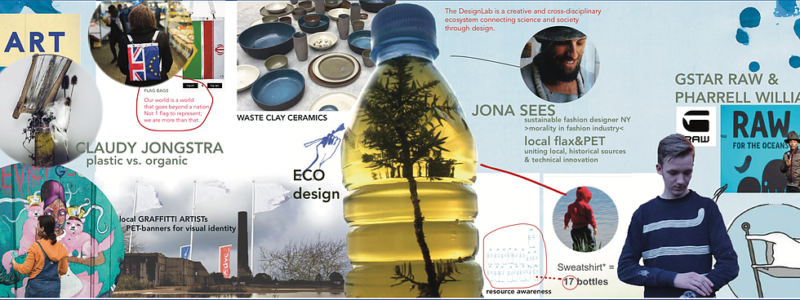

Waste No Waste has been the brainchild of international textile artist Claudia Jongstra, who thinks about waste both in terms of materials and knowledge. Her pop-up lab takes the knowledge once vital to communal living—weaving and bread baking—and applies them to sustainable practices in farming and recycling. When I went in, one woman was proofing dough; another was cutting strips of plastic bags to be threaded in her wall loom. Apprentices worked on site and passed along their knowledge from Jongstra and New York chef Dan Barber to others. According to the website, the project lasted two weeks to show:

There is no waste of society. During the whole period of the Waste No Waste Factory, the attention is directed to the social fabric of Groningen and its potential. Providing lectures and public events offers a stage and inclusive context in which everyone is invited to participate. Weaving is hereby used as a vivid metaphor to integrate and connect as a whole and yet to make society’s diversity visible; weave and strengthen the local social fabric!

PET bottles became thread, fabric, and art. And then everyone broke bread together. Even the building was “no waste.” An architectural firm donated the materials that would later go into new homes.

All things are connected in making sure craft and knowledge are sustainable for the planet. These three images are from Claudia Jongstra’s Waste No Waste.

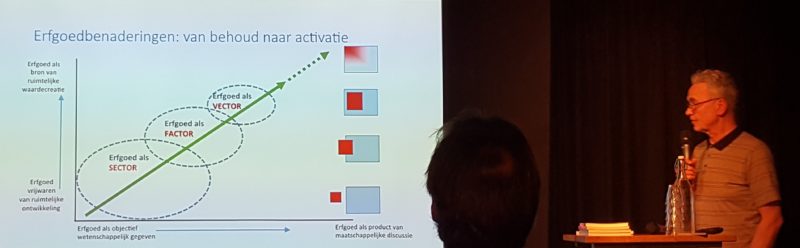

This version of erfgoed is what design thinkers are calling “heritage as a vector” in that history lives through the formation of new social collectives. Dr. Martijn de Waal at the Play and Civic Media Lab of the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences compares this version of heritage to those who want to cordon off historical spaces (“heritage as a sector”) or simply repurpose those spaces for commercial uses (“heritage as a factor”).

“When we empower communities to be heard, we maximize public values in that space,” de Waal told me. He reflected that the danger in these pop up projects is that the curators can get burnt out. For that reason, he said, design thinking needs to consider better governance models to help communities sustain their ideas to bring heritage alive through social practices and into communal spaces. “We need infrastructure for the commons.”

So what do we need in New Orleans to take a plastic bottle out of the waste stream and clothe our homeless? And what kinds of conversations might we have over the hours it takes to proof a loaf? And how can policy makers better support those living, social, and sustainable practices as part of our collective way life and not another festival? Things to consider as we give thanks for what we have.

Reimer Knoop of the Reinwardt Academie discusses a design thinking model for doing heritage placemaking. This theory is elaborated in Visie erfgoed en ruimte: Kiezen voor karakter 2011. De onderzoeksagenda Karakterschetsen (Witsen 2013). Photo by Vicki Mayer.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.