Editor’s Note: The following series “Via Voodoo Vie: an Exploration of Voodoo in NOLA” is a week-long series curated by Emily O’Connell as a part of the Digital Research Internship Program in partnership with ViaNolaVie. The DRI Program is a Newcomb Institute technology initiative for undergraduate students combining technology skillsets, feminist leadership, and the digital humanities.

The history and tradition of Louisiana Voodoo has become a unique part of the culture of New Orleans. However, it goes deeper than the Voodoo that has been popularized by the media and tourist attractions. With origins in West Africa and Haiti, brought to Louisiana by enslaved and freed people of color, Voodoo has a rich and often overlooked history, so let’s explore how Voodoo has made its mark on the city and how the city has, in turn, influenced the perception of Voodoo. Ever heard of a Jazz Funeral? Or been to a second line? Or seen the Mardi Gras Indians during Carnival? Did you know that these traditions have roots in Voodoo (also known as Vodou or Vodun)? Learn more about how Western African practices have influenced New Orleans culture and tradition. Originally published on June 22, 2017.

“Cry at birth and laugh at death.”-African proverb.

To understand the ghede, the voodoo spirits of death and fertility, it is necessary to have some understanding of voodoo itself. But that is not easy. It is a religion whose ancestors hail from the indigenous religions of West African peoples, born in their camaraderie as slaves in the Caribbean, and finding its way to North American among the refugees of the Haitian Revolution. It is a gallimaufry of ancient African spirits and deities, old world European lore and myth, Catholic symbolism and litanies. The name itself has a swath of spellings and origins. In West Africa, the Ewe word vodu means ‘fear of the gods,’ and in Dahomey, vodun was used as a name for all deities. The spelling changes depending on the context, region, or inclination of the author, but is generally referred to as vodou in Haiti, vodun in Benin, West Africa (formerly Dahomey), and voodoo in New Orleans (Touchstone, Blake. “Voodoo in New Orleans” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. New Orleans: Louisiana Historical Association. Vol. 13, No. 4 (Autumn, 1972), pp. 371-386. Print.).

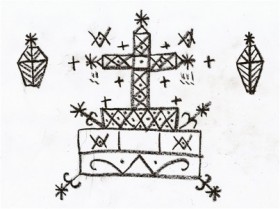

Drawing of a sacred cosmogram by the author.

Voodoo practitioners conjure the spirit who reigns over the ceremony being performed. Each spirit is represented by a vévé, or sacred cosmogram, which is either drawn onto the ground with flour, or symbolically into the air. There are many spirits within the voodoo pantheon, synthesized together from all those worshipped by the many ethnicities of its homeland. When individuals from different groups were captured and sold into slavery, they were brought together in the New World colonies, and their beliefs melded together over time into a unified spirituality. This was then further infused and contorted by existing European pagan lore and enforced Catholic dogma. After the Haitian revolution, great numbers of plantation owners and their slaves came to New Orleans, and with them came Haitian vodou. The resulting panoply of spirits and rituals is at once mystifying and intriguing. It is no wonder that the esoteric religion of voodoo still manages to confound the western mind.

Within the voodoo pantheon are a family of loa, or spirits, called the ghede. Also written as guédé or gede, these are the voodoo spirits of death and fertility. Papa Ghede is the dominant spirit, and is often portrayed in his formal attire of black tails, a top hat, and darkened sunglasses. His appetite is insatiable, a metaphor for his constant thirst for souls. He washes down his food with rum spiced with hot peppers, and smokes cigars or cigarettes after his meal. When a voodoo spirit is conjured, they mount one of the practitioners, riding them like a horse. When one is ridden, they are possessed not unlike an evangelical Christian filled with the Holy Spirit. Their eyes take on a the demeanor of the spirit and their movements take on its character (Deren, Maya. Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti. New Paltz, NY: McPherson, 1983. Print. p.105-7). Though there are a handful of temples in New Orleans, voodoo is more publicly visible in its influence on New Orleans traditions. In the cortege of a jazz funeral and the regalia of the Mardi Gras Indians, voodoo spirits may be glimpsed in the costume, dance, ritual objects and symbolic imagery.

In voodoo cosmology, Ghede is the spirit of life and death, the corpse of the first man. He is associated with fertility and children, representative of our eternal erotic nature. ‘Through his randy, playful, childish, and childlike personality, Gede raises life energy and redefines the most painful situation—even death itself—as one worth a good laugh’ (Brown, Karen M. C. Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991. Print. p.330). Once the cortege of the jazz funeral departs the cemetery, the wails of mourning transform into ululations of joy and celebration. The band kicks into an upbeat number, and wild and raucous dancing ensues. ‘Among the Kongolese brought as captives to Louisiana, it was indeed the tradition first to vent the soul’s sorrow with the customary weeping and wailing and then to accompany the dead to their resting place with much rejoicing. Decorum required that the mourners sing, beat the drum and tambourine, and dance the soul to its new home’ (Osbey, Brenda M. “One More Last Chance: Ritual and the Jazz Funeral.” The Georgia Review. 50.1 (1996): 97-107. Print). The funeral dance is called the “banda” and is performed in honor of the dead. Sexual in nature, it is “the dance of Guedeh La Flambeau [who] is the flashing brilliance of an orgasm, often called ‘the little death.’ This dance originates in Africa where death is not mourned, it is believed that the deceased must be provided with the necessary conditions for a happy passage beyond.’ The dance is copulatory because their can be no rebirth without sex. It is a display of vitality and eroticism, which are inextricably linked with the cycle of life and death (Hall, Ardencie. New Orleans Jazz Funerals: Transition to the Ancestors. 1998. Print. p.194). The dance is also performed in order to ‘cut the spirit loose’ so that it will not be able to slip into the body of an unsuspecting friend or relative. People used to say that the soul, when first released at the graveyard, would try to invade the living persons present and take over their bodies—in short, retreating from the other world’s uncertainty. So the family would shake from head to toe waddling back home. That would keep them from being easy targets. It was an eerie sight to see. Now the ‘wobbling’ walk in fear of possession is just part of a farewell dance from the crowd as the family releases the soul to its destiny (Touchet, Leo, and Vernel Bagneris. Rejoice When You Die: The New Orleans Jazz Funerals. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1998. Print. p.22). As it is said in the Kongo, Dance with bended knees, lest you be taken for a corpse.

Leading the cortege is the grand marshall. With his or her steps (side-step-cross-touch), they trace the continuous movement of life. ‘Each step marks the four points of the sun or the motion of human beings from birth to spiritual transformation.’ In both jazz funerals and Mardi Gras Indian parades, the use of flags, umbrellas, sashes and handkerchiefs all serve a ritual purpose. Umbrellas are often decorated with vévé and other voodoo iconography such as moons, stars and planets. ‘The opening of the umbrellas signify the release of the dead’s soul and the return to life while also reminding us we all walk in the shadow of death. The secondliners carry white handkerchiefs which they wave to symbolize the flight of the spirit” (Hall, Ardencie. New Orleans Jazz Funerals: Transition to the Ancestors. 1998. Print. p.182-4, 198). Nikusa minpa, the process of agitating cloth to open the door to the other world with honor, becomes transformed into dancing and spinning bright umbrellas in the jazz march from the cemetery (Thompson, Robert F, and Joseph Cornet. The Four Moments of the Sun: Kongo Art in Two Worlds. (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1981. Print. p.203). ‘Flags are central because they signal the supernatural beauty of the spirits and their imminent presence in religious ceremony.’ Flags are also often adorned with the vévé of spirits, and the sequin work on them is associated with the spirits and pwe, the points of power drawn as dots or asterisks in the vévés (Turner, Richard B. Jazz Religion, the Second Line, and Black New Orleans. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009. p.44). Color also plays an important role. White is the African color of mourning, so it is common to see white ribbons, white doves, and white raiment in association with funerals.

The feathers and beadwork of the Mardi Gras Indians are also symbolic of the spirits, as is found in Kanaval in Haiti as well. The feather and sequin arts originated in the Kongo. There, divine healers are known as ‘leopards of the sky’ predatory birds with feathers around their head and covered with the spots of the cat; ‘spotted mediatory felines moving between the two worlds, bush and village.’ On the streets of New Orleans, we see this in the feathered headdresses of the Mardi Gras Indians, in the glittering sequins of their suits. The drapo, ritual flags in Haitian vodou adorned with beads and sequins, represent ‘the supernatural beauty of the spirits and their immanent presence in a religious ceremony.’ Sequin artists dedicate their lives to the form, as Mardi Gras Indians do in the beadwork and creation of their suits, headdresses and flags. In Haiti, ‘salutary parading’ involving two sequined flags is used to invoke the vodou spirit, Ogou, which can be seen re-created in the performances of the spy boy and flag boy, manifesting ‘the religious hierarchy of Haitian vodou.’ The earlier practice by Mardi Gras Indians of wielding weapon can be traced to the opening ceremony in Haitian vodou, ‘when the master of ceremonies wields the sacred machete or saber in a mock battle as he dances between the flags in the temple. In both cases, the weapons are related to the ‘warrior spirit’ of Ogou, who ‘bestows the power to survive.’ His power has endured, indeed, as the traditions of the jazz funeral and the Mardi Gras Indians grow stronger than ever, driven by the force and spirit of the American descendants of West Africa (Turner, Richard B. Jazz Religion, the Second Line, and Black New Orleans. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009. p.56-8.).

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

[…] Voodoo has an undeniable presence in the music of New Orleans from its roots in West African and Haitian traditions. Voodoo’s religious practices have been integrated into the city’s musical expressions, sometimes in surprising ways—for example, the iconic Jazz Funeral. […]