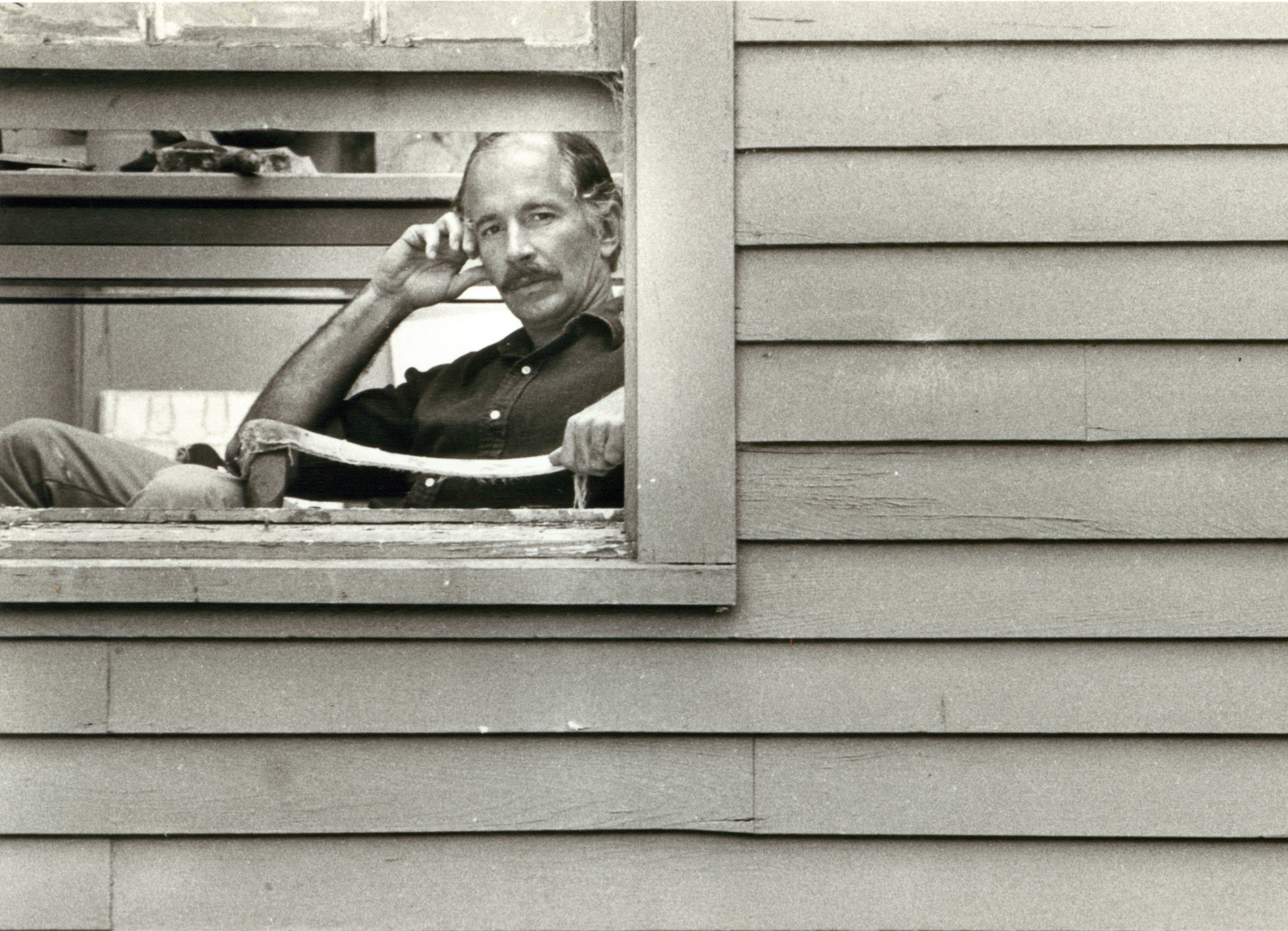

The artist, George Dunbar, in his studio window (photos provided by: Folwell Dunbar)

The artist, George Dunbar, in his studio window (photos provided by: Folwell Dunbar)

When I was in college, I went on a Southern Literature binge. I read everything by Faulkner, Williams, and Twain. I read A Confederacy of Dunces (my all-time favorite), All the King’s Men, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, The Moviegoer and Deliverance. And, of course, I read Margaret Mitchell’s bestseller, Gone with the Wind, and Shelby Foote’s epic, The Civil War: A Narrative.

I had gone to high school north of the Mason-Dixon line, and was trying to reconnect with my southern roots.

When I eventually found my way back home to Louisiana, I met many of the characters from those books, including Tom Sawyer, Willie Stark, Big Daddy, Binx Bolling, Blanche DuBois, Celia and yes, even Ignatius J. Reilly.

These real “fictional” characters included my parents. My mom, with her black lipstick, wicked sense of humor and eccentricities to spare, could have easily been lifted from the pages of a Tennessee Williams play. My father on the other hand, was pure Atticus Finch. He embodies all the good and none of the bad from the Deep South.

My father, George Dunbar, was born in New Orleans in 1927, the year of the Great Mississippi Flood, and he grew up in the Garden District during the Great Depression. After high school, he joined the navy and served in the South Pacific. When he returned from the war, his father, a respected lawyer who had started a successful firm, tried to convince him to join the family business. Instead, my father used the G.I. Bill to attend art school in Philadelphia. He wanted to pursue his own dreams and his own passions.

After he graduated from college, my father was met with almost immediate success. He was in a group show with the famous action painter, Franz Kline, and he had his first solo show at the Dubin-Luch Gallery in 1953. He won a regional competition at the Delgado Museum of Art (now the New Orleans Museum of Art) and was awarded a show at the museum. Art in America featured him in their “New Talent” issue; and Betty Parsons, the famous art dealer and collector who had discovered and shown many of the early abstract expressionists like Mark Rothko, Jasper Johns, and Jackson Pollock, admired his work. He was poised to take off. He set his sights on New York City, the center of the contemporary art world.

But then, as is often the case, life intervened.

“My mother got sick,” my father told me, “so, I stayed in New Orleans to take care of her.”

“And then I eventually met your mother,” he continued with a wistful smile. “She was on a date at the museum, so I couldn’t exactly talk to her. But, she was definitely the most beautiful woman I had ever seen. I later ran into her at Tujague’s in the French Quarter and asked her out. When we decided to get married and have children, I knew that I didn’t want to raise a family in a big city like New York – or even New Orleans for that matter. So, I bought a piece of property out in the country. I figured you kids would enjoy growing up on the bayou.”

“We did,” I confessed.

The artist on his tractor (photos provided by: Folwell Dunbar)

The artist on his tractor (photos provided by: Folwell Dunbar)

“I also realized that it would be hard to support a family selling art,” he admitted. “So, I started to develop land on the side. I’d ride a tractor during the day and paint at night. It’s not exactly what I had in mind when I went to art school, but, I grew to like it. The money I made in real-estate allowed me to take chances as an artist; and my background in the arts influenced how I developed land. It all worked out in the end.”

When I asked my dad if he had any regrets, he said, “Sure. Who doesn’t? I think I could have hit it big in New York. But in life you make sacrifices…”

He then mentioned two of his favorite films, On the Waterfront and Casablanca. He identified with the underdog “contender” standing up to corrupt union bosses, and with the romantic dreamer who sacrificed one love for another.

Whenever I think of my dad, I am reminded of the movie about the English philosopher and statesman, Sir Thomas More. Like More, my dad always took the high road. He was (and is) A Man for All Seasons.

Though he stayed Louisiana, my father had a successful career, or, should I say, “careers.” As an artist, he and several of his friends started the first gallery for contemporary art in the city of New Orleans; he had regular shows in the city and around the country; his work was collected by prominent individuals, businesses and museums; and, he received numerous accolades, including the Delgado Society Distinguished Art Award and the Louisiana Governor’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

As a businessman, my father developed more than seventy subdivisions in Louisiana and Mississippi. He dug canals, built roads, planted trees and improved hundreds and hundreds of acres of land. He imposed building restrictions to protect the land’s natural beauty, and he donated property to the Nature Conservancy to preserve indigenous species.

Whenever people are asked about my father, they always mention his success in art and business. But, inevitably, they also talk about his character. They tell stories about how he once testified against the Klan, how he gave medals to children who could swim the length of a pool, how he was constantly auctioning off paintings to support worthwhile causes (see this month’s “Art in Bloom”), and how he never allowed anyone to ever pick up a tab – EVER! They use words like “disciplined,” “generous,” “genuine” and “integrity” to describe him. “George Dunbar is my hero,” they often say.

And, if that weren’t enough, my father is also one of the most elegant men you will ever meet. He’s stylish and debonair. He has a great eye and impeccable taste. He’s like a southern version of Cary Grant.

A number of years ago, a friend of mine got married in the St. Louis Cathedral. It was late June and oppressively hot. People scurried into the cool church, relieved to escape the midday sun. When my father entered the nave, all eyes craned in his direction. He was wearing a beautiful white Armani suit and a pressed white linen shirt. He carried a Panama hat and a cane. He looked like a retired James Bond, as played by Sean Connery, at Chris Blackwell’s Jamaican resort, Goldeneye. With their eyes fixed on him, everyone in the room felt bad for the bride.

When he sat down next to me, he whispered in my ear, “What’s wrong with this generation son? There are people here wearing dark blue suits. Everybody knows you’re supposed to wear white linen in the summer. It looks good and makes sense. Along with seersucker, it’s part of the New Orleans vernacular.”

My dad dedicated his life to creating visually beautiful things. He makes them with paint, clay, and metal leaf; he makes them with earth, trees and even clothing.

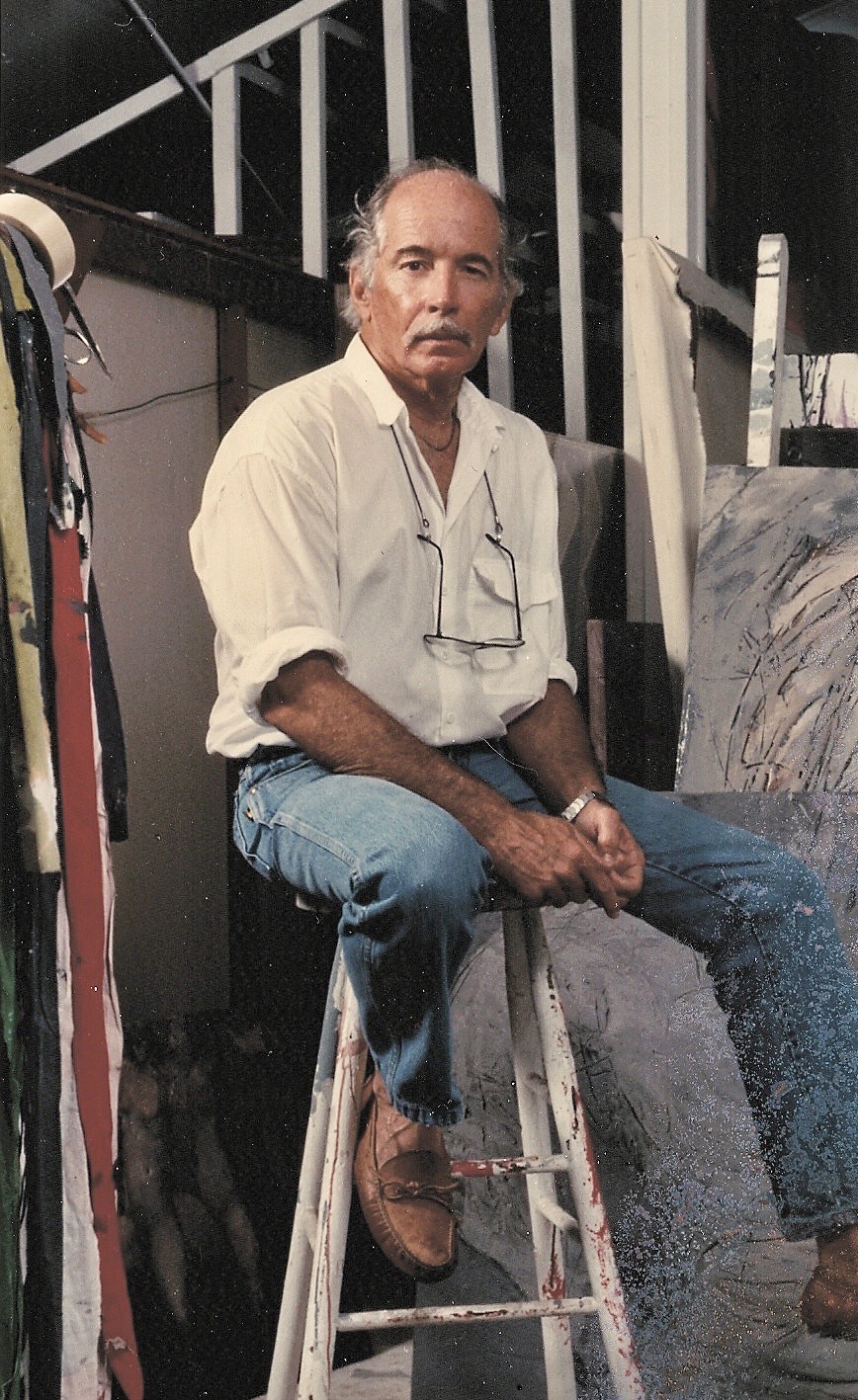

Dunbar in his studio circa 1985 (photos provided by: Folwell Dunbar)

In 2012, my father was honored at The New Orleans Museum of Art’s “Love in the Garden” celebration. Each honoree was called up onto the stage where they were presented with an award and gave a short talk. The final recipient was a young woman who had started a nonprofit. After her acceptance speech, it became apparent that the organizers had miscalculated the number of chairs needed. There was nowhere for the woman to sit. My father, by far the oldest person there, instinctively stood up and offered her his chair. It was a small gesture, but it spoke volumes. Knowing my dad, no one seemed surprised.

When I told my dad I was writing an article about him being a gentleman, he immediately demurred. “If it’s true, I take none of the credit,” he said. “It’s how I was raised.”

“In the wake of the #MeToo movement,” I said, “do you think chivalry still has a place?”

“I hope so,” he said. “I’ve always tried to treat everybody the same.” He then smiled and added, “With the exception of women; I treat them better.”

In high school, I had a relationship that was floundering. When I asked my dad for advice, he repeated a line he had used many times, “When all else fails, try to act like a gentleman.” It was sound advice from a credible source.

Recently, while taking a walk with my wife, she turned to me and said, “You know, I think your father may well be the only true gentleman I know.”

“Really?” I said, a bit disappointed that I hadn’t made the cut.

“Absolutely,” she replied. “Can you think of any others?”

“No, not really,” I said, “To paraphrase the title of that book by Walker Percy, my old man is possibly The Last Southern Gentleman.”

Folwell Dunbar is a seasoned educator, an aspiring artist, and the proud son of George B. Dunbar. He can be reached at fldunbar@icloud.com.

In addition to being a Southern gentleman, George Dunbar is a working artist. He is currently preparing for a show in November at Callan Contemporary. To learn more about him and his work, go to www.georgedunbar.com.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.