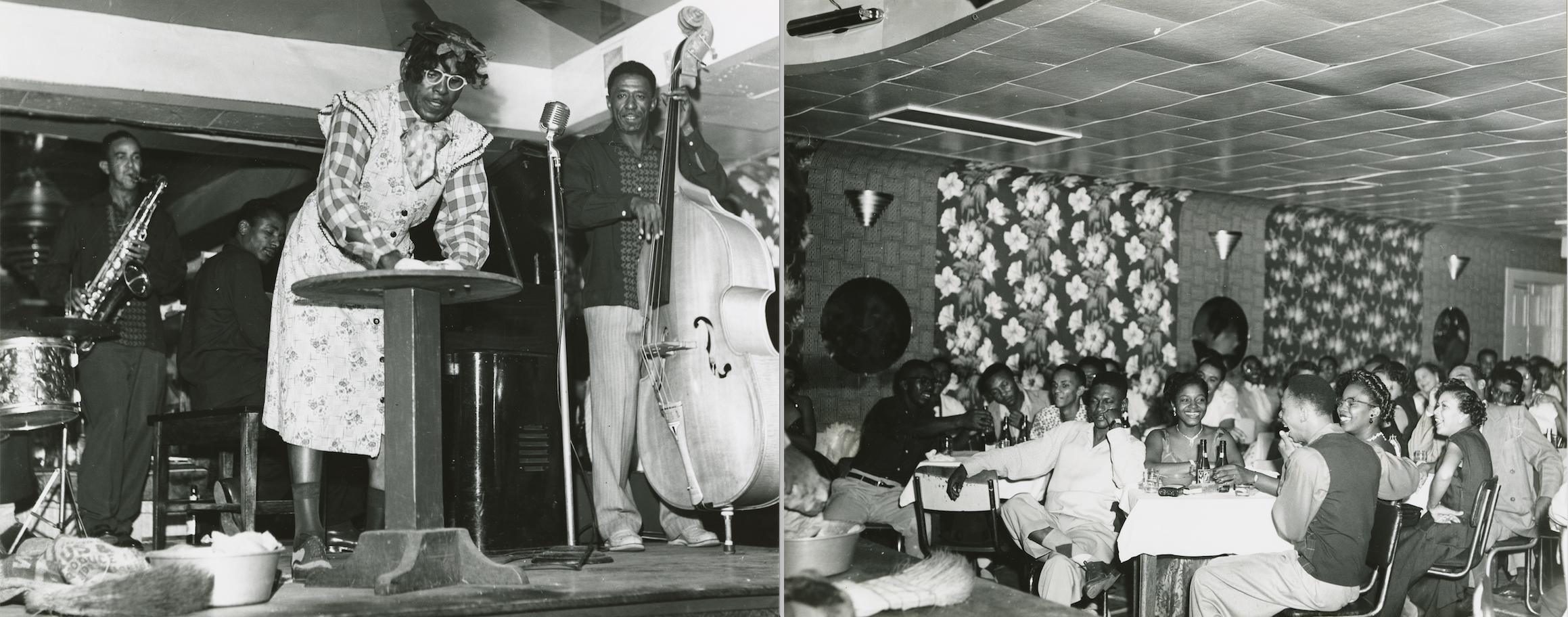

The Dew Drop Inn, 1953. Courtesy of the Ralston Crawford Collection, Hogan Jazz Archive, Tulane University

In the 1930s, a typical New Orleans sandwich shop opened near the Magnolia Housing Projects in Central City, New Orleans. But in 1939, owner Frank Painia, an African American barber from Plaquemines Parish, decided to expand this establishment to form a hotel, which then became known as the acclaimed Dew Drop Inn. Its reputation grew after Painia decided to add a nightclub in 1945, with the hopes of appealing to African American citizens looking to be a part of the entertainment scene. At the time, segregation laws were still in force, so most of the clubs throughout the city prohibited black people from entering. With Painia’s entrepreneurial spirit, the Dew Drop Inn became a central location for the African American music scene (3).

Not only did the nightclub appeal to musicians, but it also promoted a large variety of acts to amuse the audience. “The stage featured comedians, snake dancers, magicians, female impersonators, and stunt performers who chewed glass or lifted tables with their mouths” (3). This club generated an atmosphere so compelling and progressive that it appealed to just about any kind of person, including white people.

Although the law enforced segregation of white and black people in clubs, Painia embraced anyone who came into the Dew Drop Inn, which created a culture of integration. It was this attitude of acceptance that likely attracted the variety of audience members and performers, because it resonated with the New Orleans motif of accepting all kinds of culture; however, this friendly mindset also resulted in Painia being arrested numerous times. Although he was utilizing his club as a chance to promote desegregation, he eventually became fed up with the harassment and wanted to play a larger part in Civil Rights movement. He decided to sue the city in federal court for unconstitutional treatment. However, before any verdict was made, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 had been approved by the president (Lyndon B. Johnson), marking the end of public segregation (2).

Performers and audience members of the Dew Drop Inn, 1952. Courtesy of the Ralston Crawford Collection, Hogan Jazz Archive, Tulane University

Before 1964, the Dew Drop Inn was thriving. Even though the club hosted many different types of performances, it appealed most to black musicians. It became such a hotspot that black musicians all over the country felt the need to perform at the club in order to make a career in music. As blues musician Joseph August (also known as Mr. Google Eyes) stated, “Whether you were from out of town or from the city, your goal was the Dew Drop. If you couldn’t get a gig at the Dew Drop, you weren’t about nothing” (3). The venue attracted many prominent musicians such as Ray Charles, Otis Redding, and James Brown (4). Young performers traveled great distances to have the chance to not only meet the famous performers, but also get the chance to play with them.

With this ambience of collaboration and acceptance, the Dew Drop Inn became crucial to the expansion and evolution of rhythm and blues. Additionally, the club harbored a sense of friendly competition where musicians would attempt to best one another on stage in order to stand out, which created a drive for performers to get creative. And unlike any other club in New Orleans, it was open all the time, consistently providing a source of entertainment (1).

The Dew Drop Inn today, which is located on Lasalle Street

However, once the laws banning integration were removed, black people in New Orleans began going to different music club throughout the city, which led to the declining popularity of the Dew Drop Inn. The nightclub closed in 1969, and the venue became a hotel.

When Hurricane Katrina hit, the building no longer provided suitable living conditions due to the flooding and damage, so the hotel had to close. While there have been numerous efforts over the past decade to revive the venue, most have fallen short (2). But there is now a movement by Kenneth Jackson (the grandson of Frank Painia), Harmony Neighborhood Development, and the Milne Inspiration Center to rebuild every aspect of the Dew Drop Inn.

If you’d like to check out the campaign, then you can click here. Walking by the building now, it may be hard to recognize its role in New Orleans history, since it’s currently a vacated building with a structure that’s fading away, but its contributions should always be remembered.

Bibliography

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.