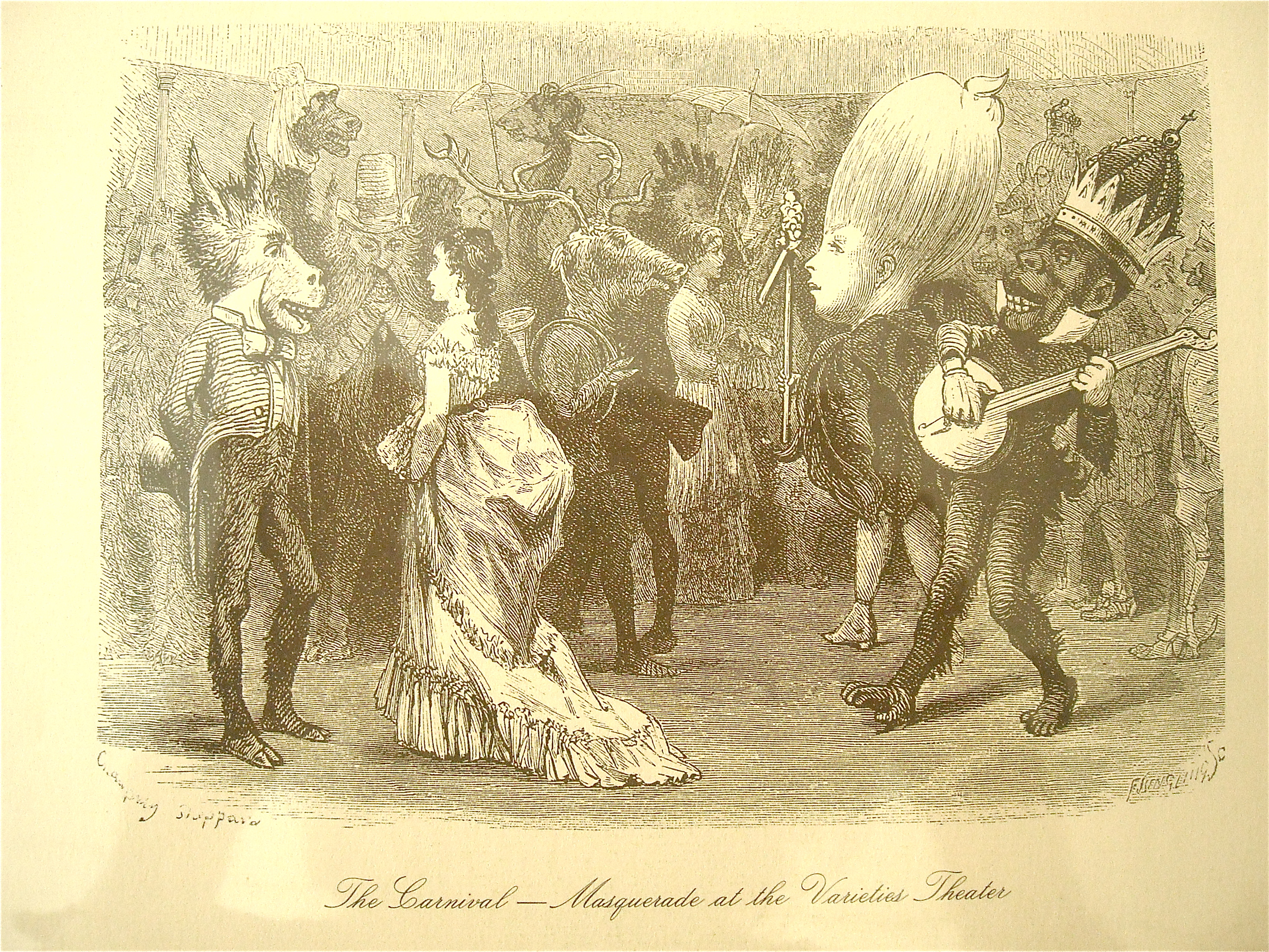

A typical Mardi Gras masquerade seeing as krewes were organized around white affluent cosmopolites.

In 1873, the Mistick Krewe of Comus, and most all other krewes, were comprised of wealthy, white aristocrat males. The Krewe of Comus was secretive – comprised of bank presidents, cotton merchants, and lumber barons — who joined by invitation. The cost of joining the krewe was high, so only the wealthiest of the upper class could join. The most elite, powerful men were crowned the kings, and that title reinforced their status.[1] This perpetuated the culture of white supremacy not only within the Krewe of Comus, but within all of the Mardi Gras krewes at the time.

The Mistick Krewe of Comus’ 1873 parade theme was entitled “The Missing Links to Darwin’s Origins of Species.” This was one of the first Mardi Gras parades to take an actively political stance in the era of Reconstruction. This parade was a direct attack on Reconstruction politics, Carpetbaggers, and the status of black people in society.

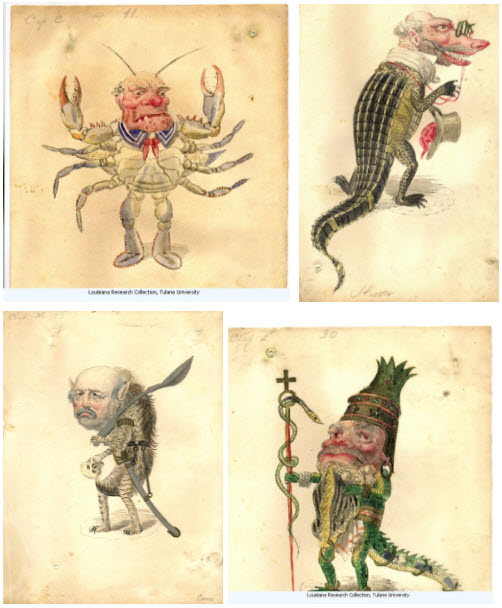

The parade included elaborate costumes representing unnatural specimens, critiquing the “unnatural direction” that Reconstruction had taken New Orleans. Notable political figures such as Ulysses S. Grant, Benjamin Butler, Henry Warmoth, and Algernon Badger were parodied and represented as mockable creatures.[2] In order to fully understand the nuances of the 1873 parade, it is important to understand the unique politics of Reconstruction in New Orleans prior to Mardi Gras of 1873.

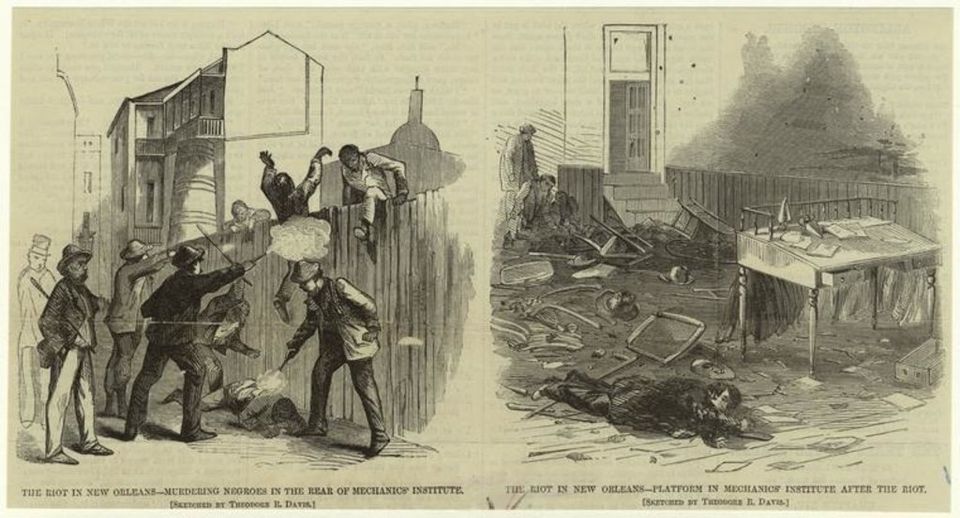

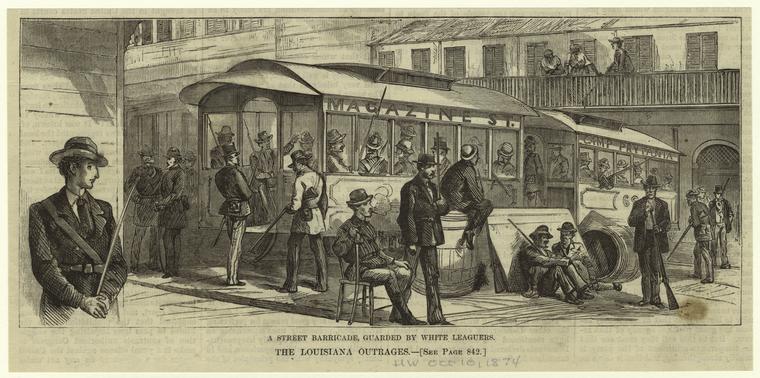

Images depicting the struggles felt and voiced during the Reconstruction Era in New Orleans.

Prior to Reconstruction, New Orleans was seen as an anomaly among southern states and cities. The South’s largest city, its major port, and its financial and intellectual capitol, it had fallen into the hands of the Union early in war [3]. New Orleans had a black population of approximately 50,000 people at the time. That population included a large population of free blacks, many of whom were free, wealthy, and highly educated, French-speaking, Catholic Creoles; a peculiarity not seen in other southern cities.

Despite the distinctiveness of New Orleans, the racial tensions that came with the Reconstruction period were as bad as any other southern city. In the 1865 elections the Democrats promoted rhetoric such as “God forbid the negro ever be elevated to our level,” which made it clear that black suffrage was unacceptable by most southern white men[4].

Throughout the late 1860’s there were a number of race riots that exacerbated the racial tensions and exposed the vulnerability of the black population in New Orleans[5]. Slavery ended with the war, but Democrats in New Orleans fought to uphold the idea that black people, even though they were no longer slaves, were inferior. The establishment of New Orleans under military rule following the passage of the Reconstruction acts further worsened race relations in the city[4].

At the time, New Orleans was governed by Henry Clay Warmoth, a Republican who was despised among the Democrats, who saw him as an incompetent, corrupt, carpetbagger[5]. Warmoth created the Metropolitan Police in order to work around the prohibition of state militia. The creation of the Metropolitan Police increased animosity towards Warmth from the white supremacists. It was not only the establishment of this pseudo-militia that upset the Democrats, but also the fact that black men served beside white men as a part of the force. Black men had been legally armed and put into authority by Warmoth, and the Democrats saw this as a threat to their status[6]. In 1869, Algernon Badger became superintendent of the Metropolitan Police; he was seen by Democrats as another incompetent northern Republican.

Political paraodies from the 1872 election in New Orleans led to parade costumes full of mockery and criticism.

The election of 1872 was the first in which the Confederates had their right to vote reinstated and there was a possibility of Democratic control. Yet, Democratic influence was diminished, and as a result Republican William Kellogg replaced Warmoth as governor of Louisiana, with support from President Ulysses S. Grant.

Former Confederates hated Kellogg even more vehemently than Warmoth, further agitating racial tensions in New Orleans as Kellogg worked for desegregation and other Republican issues[7]. It is important to note that Grant’s support of Kellogg was perceived negatively by the Democrats of New Orleans, and furthered the hatred for him that had been sparked by the passage of the Reconstruction acts. The 1872 election was still fresh in the minds of the white supremacists as the 1873 Mardi Gras parades approached and the Krewe of Comus prepared to make their collective political statement.

Political figures Henry Warmoth, Algernon Badger, and Ulysses S. Grant were main points of mockery during the Missing Links parade. They were targeted specifically due to their Republican views and actions that supported a more equitable and desegregated New Orleans. Clearly, the white elite that made up the Mistick Krewe of Comus opposed the political state of the city, and decided to express their discontent through the 1873 parade. The parade did not have floats, but rather a series of paper mache costumes depicting various unnatural species. Many of these costumes were seemingly random creations, but there were many that held deep political significance.

Henry Warmoth was portrayed as a rattlesnake in the parade to show the citizen’s disdain for him and his ideologies.

Henry Warmoth was one of the many political figures attacked throughout the parade. He was portrayed as a snake, most likely referring to the fact that he was despised for being a Carpetbagger, a derogatory term applied to northern men who moved to the South during the Reconstruction era and became involved in local politics. Democrats detested the fact that Warmoth became involved in local politics when he had no local ties to the city or the area. They saw him as corrupt, exploiting the people and the city for his own personal gain. The political hatred Warmoth earned among white elite led to his portrayal as a venomous snake, one of the Missing Links.

Algernon Badger was another point of mockery in the parade. He was caricatured as a bloodhound, most likely because he was often met with opposition from the White League and other white supremacist groups.

Warmoth created the Metropolitan Police in response to the ban on state militias. The force was integrated, meaning that black officers had been given the same power and authority as white officers in situations of conflict. Due to this, the head of the Metropolitan Police, Algernon Badger was another point of mockery in the parade. He was caricatured as a bloodhound, most likely because he was often met with opposition from the White League and other white supremacist groups[8]. It was no surprise that he was portrayed as a bloodhound in the parade, making a mockery of both him and the police force.

Even president Ulysses S. Grant was not off limits from the mockery and criticism during the parade.

Ulysses S. Grant had been president and had just been reelected for a second term. Having been arguably the most important general in the Union Army, former Confederates despised him. Grant had approached Reconstruction with the intention of protecting and preserving civil rights for the former slaves. His support of the Fifteenth Amendment and his policies against the terrorist acts of the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist groups intensified the opposition against him[9].

Grant was portrayed as a tobacco grub in the parade, mocking his incessant cigar smoking. In the original watercolor done of the creature depicting Grant, he is holding a box under his arm that says “tax paid,”perhaps attacking the corruption scandals that were brought against him [figure above].

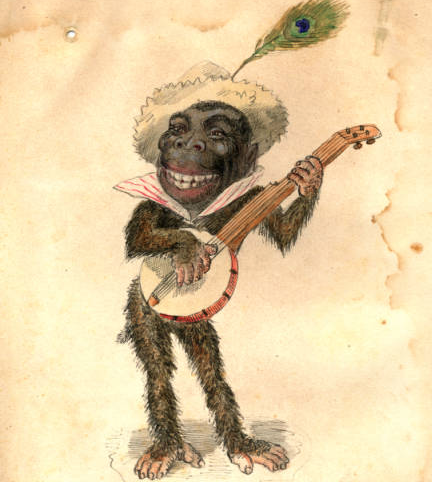

The racist actions and portrayals of black southerners was not only part of the history of the white supremacist parades, but the racist actions were also shown in their portrayal of blacks in the parade.

Not only was the Missing Links parade an attack on the current political climate of the times, it was also a scathing attack on the social climate as well. In a blatant display of racism, the parade portrayed a half man, half gorilla as the ‘Missing Link,’ who closely resembled a black man.

And — last link in the might cable that binds unwilling Man to the indifferent Monads, appeared the gorilla; a specimen, too, so amazingly like the broader-mouthed varieties of our own citizens, so Ethiopian in his exuberant glee, so fixedly at home in his pink shirt collar, so enraptured with himself and so fond of his banjo, that the Darwinian chain wanted no more links, and the people no stronger argument [10].

A tableaux depicting the fears of white supremacists, that blacks would overtake them and pull control from the whites.

One of the tableaux displayed the gorilla when he was crowned and opened the gate to an old plantation that was supposed to represent “Darwin’s Eden”[11]. In the final tableaux the gorilla stands atop a set of stairs, surrounded by the unnatural creatures that had walked in the parade. The tableaux depicted the King of Comus at the bottom of the stairs, supposedly under the rule of the Gorilla, yet unaffected by the creatures around him[12].

This inverted hierarchy represented the seemingly backwards turn that social standings had taken in the Reconstruction era with the perpetuation of desegregation and other political policies that granted rights to freedmen.

The white supremacists that made up the Krewe of Comus were threatened by the changing social order. The consensus among former Confederates was that this social progression was backwards and went against natural social order. Representing the black man and various prominent Republicans as the creatures that made up the Missing Links stated that they were subhuman creatures, less than the likes of the white man and deserving of a lower status.

A depiction of The White League.

The inversion of the gorilla and the King of Comus on the tableaux followed the carnival tradition of flipping things upside down. It was mocking what the white supremacists incorrectly saw as the Republican ideology – black men having power over white men. This was a White League interpretation of Reconstruction “the most absurd inversion of the relations of race” [13]. For so long white supremacists held top positions of power in society. When any social change threatened to disturb that status, the desire for power and control overruled any moral compass – leading to public displays of racist political commentary, such as the 1873 parade.

The Missing Links parade, while not an event in a political arena, was an inherently political attack. The message was clear: black men were inferior. They were subhuman. They were less evolved than the white man and closer to an ape than to a human.

While the white supremacists may have had limited political power at the time, they used the social capital they possessed as members of a Mardi Gras krewe to make their own kind of political statement. Using the Mardi Gras parade as a political platform allowed the members to hide behind their masks of secrecy, shielding their personal identities from any backlash they may have faced if they made a stance openly. Despite the fact that individual members’ identities were secret, the group as a whole was known. It was the rich, white Democrats who had advocated for a system of inequality from the beginning.

Sources:

[1] Elizabeth Leavitt, “Southern Royalty: Race, Gender, and Discrimination During Mardi Gras From the Civil War to the Present Day,” Representing Women in the Civil War Era, (February 2015) Online article.

[2] Joseph Roach, “Carnival and the Law in New Orleans”, TDR 37 (Fall 1993), 63-66.

[3] Melinda Meek Hennessey, “Race and Violence in Reconstruction New Orleans: The 1868 Riot,” Louisiana History 20 (Winter, 1979). 77-89.

[4] Joe Gray Taylor, “New Orleans and Reconstruction”, Louisiana History Vol.9 No. 3, p.192, (Summer, 1968).

[5] Hennessey, “Race and Violence in Reconstruction New Orleans: The 1868 Riot,” 79, 80, &84.

[6] Taylor, “New Orleans and Reconstruction,” 196.

[7] Taylor, “New Orleans and Reconstruction”, 201.

[8] Thomas Hunt, “1874 White League Riots in New Orleans”, Writers of Wrongs, published September 14, 2017, http://www.writersofwrongs.com/search/label/Algernon%20Badger.

[9] John Y. Simon, “Ulysses S. Grand”, Britannica, last updated April 20, 2018, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ulysses-S-Grant

[10] “Mistick Krewe. Their Coming Out and Going in. An Object Lesson in Ancestry. Comus’s Cabinet”, Times-Picayune, February 26, 1873.

[11] Roach, “Carnival and the Law in New Orleans”, 64.

[12] Jennifer Atkins, New Orleans Carnival Balls: The Secret Side of Mardi Gras, 1870-1920, (LSU Press, 2017) p.69-72, Google Books.

[13] Ellin Diamond, Performance and Cultural Politics, (Routledge, 1996), p. 226-229, Google Books.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

[…] in promoting White supremacy and mocking Reconstruction. Their anti-Darwin costumed characters presented African Americans as the missing […]

[…] of anti-discrimination in Carnival than the krewe that started it all — the Mistick Krewe of Comus. Cradled during the period of the Antebellum South prior to the Civil War, Comus’ membership […]

[…] the number just keeps on growing. Each Krewe has a unique history and theme. The oldest Krewe is Mistick Krewe of Comus, founded in 1856. While this Krewe withdrew from parading in 1991, they still hold an annual ball […]

[…] Charles Briton drew the Mardi Gras costumes for the Mystick Krewe of Comus’ “Missing Links to Darwin’s Origin of the Species” parade in 1873. The costumes satirized the Republicans blamed by elite white for Reconstruction. […]