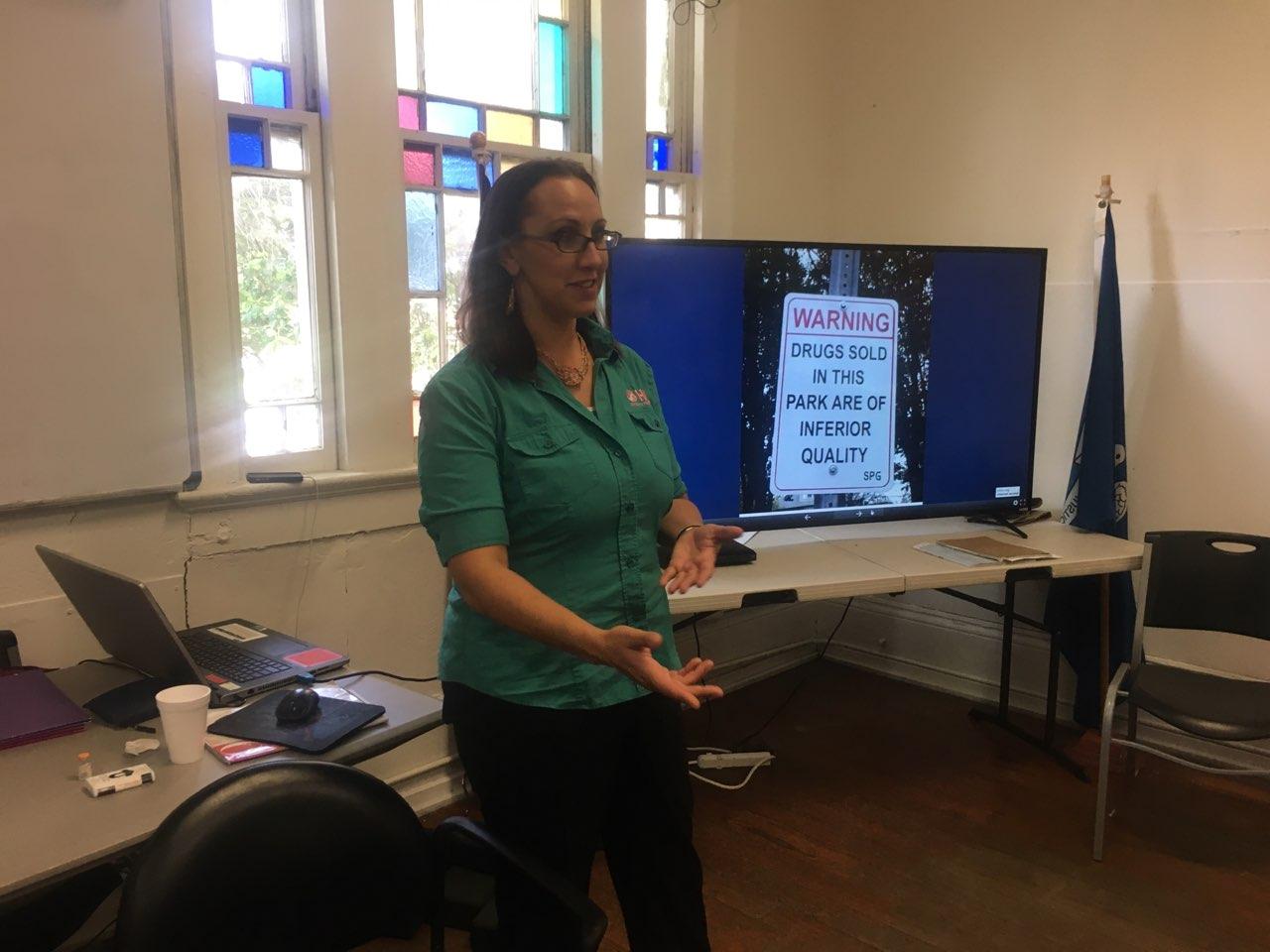

Emily Loska, outreach director of New Orleans’ Odyssey House (photos by: Odyssey House)

Emily Loska, outreach director of New Orleans’ Odyssey House (photos by: Odyssey House)

There’s a philosophy in the battle against substance use disorders called ‘harm reduction.’ “It’s based in reality,” says Emily Loska, outreach director at New Orleans’ Odyssey House. “If we wag our fingers at folks and we tell them, ‘you can’t do something,’ the chances of them responding to something are pretty low.”

“But by being pragmatic,” adds Loska, “and recognizing without any sort of judgment that risks are inherent in everything that we do, from using drugs to driving a car, and then recognizing what those risks are and then meeting each one of them…can have a more open and constructive communication with folks that are the most at risk.”

It’s in this spirit that Odyssey House has begun holding opioid overdose recovery classes.

“We talk about harm reduction as a philosophy and approach; we go over different risks for overdose, and what Nolaxone is, how to use it, and then we talk about Good Samaritan laws – laws that are in place to protect folks who intervene.” Good Samaritan Bills are wonderful in theory, but they pose significant problems given Louisiana’s culture of policing and enforcement. In the New York Times article, “They Shared Drugs. Someone Died. Does That Make Them Killers?” the situation where prosecutors are increasingly treating overdose deaths as homicides and not just going after the dealers is discussed. Friends, family and fellow users are going to prison” It is important to note that there are known jurisdictions in Louisiana where law enforcement is instructed to look for manslaughter and/or homicide charges on overdose scenes, undermining the purpose of Good Samaritan Laws (to increase those who call for help by telling them they won’t get in trouble for saving a life)

Naloxone, aka ‘The Lazarus Drug” for its ability to bring people back from near death, is an opiate antagonist, Loska says. “It’s like anti-venom for a snake bite…it blocks the receptors in the brain that adhere to opioids and renders them useless, and it can be administered by an auto injector or by a nasal spray or just an injection and a nasal spray.”

Theoretically, anyone can purchase Naloxone right from a pharmacy in New Orleans thanks to a standing order from the city’s medical director, Losca says. That said, fewer pharmacies actually carry Naloxone than in other parts of the country.

“But we’re ramping up,” Losca says. “I want to say in the last couple years since the Louisiana powers that be and our local government have recognized our place in this epidemic. They’ve really worked hard in making it more available so we’re all ramping up our education and distribution efforts in that fight as well.”

Those efforts include encouraging folks who are prescribers to always prescribe Naloxone when they’re prescribing opiates, Losca says, as well as educating the staff at drug stores about Naloxone.

Those most at risk of overdosing on an opioid are people coming out of detox or any sort of institutionalization. “Their risk is tied to a change in tolerance,” Losca says.

Tolerance can change as quickly as in two days. Another big risk factor is using alone. “And by the nature of the stigma of drug use, a lot of people are going to find themselves using alone, but having some sort of safety plan with a using buddy or somebody that can check on you is pretty important.”

Variations in potency of the drugs used, as well as the increased presence of fentanyl–far more powerful than the heroin itself–create additional risks for overdose. “Folks don’t necessarily know what it is that they’re using,” says Losca.

The signs of someone overdosing aren’t always obvious. “There’s a difference between a heavy nod and somebody who’s not responsive,” Losca says. “Somebody who’s in a heavy nod might not want to respond to you, but if you tell them you’re going to Narcan (another name for Naloxone) them, they’re probably going to respond to you. It’s not a pleasant experience. It’s instant dopesick, it’s instant withdrawal, so you want to try to get their attention first.”

But if they really are unresponsive, you should try to breathe for them through a few rescue breaths (overdoses are due to respiratory depression), then administer then Naloxone if you have it, Losca says.

“Make sure you call EMS and stay with that person until EMS arrives,” she adds. “If they wake up from the Naloxone that’s been administered, they’re going to immediately going to want to get well again, so you really want to keep the person from doing that, because if they do administer again while the Naloxone is still onboard, then they’ll effectively be putting twice as much as what put them down the first time into their system. So you really want to keep them from doing that and encourage them to go to the emergency room.”

The overdose recovery class lasts for about an hour, and at the end, people can enroll in a program to access Naloxone, says Losca. “With our folks that are the most high risk, we are able to provide Naloxone to them directly.”

To learn more, email eloska@ohlinc.org or text (504)418-1886. Additional information is also available at their iprevent website: https://www.ohlinc.org/iprevent.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.