Editor’s Note: In celebration of our own Running of the Bulls at San Fermin in Nueva Orleans (SFNO), we give you a story that involves real bulls and a real New Orleanian. SFNO will take place on Saturday, July 14. For more details on the event and how to register, click here.

The author and his friend Zack Lemann at the NOLA version of the Running of the Bulls (photos by: Folwell Dunbar)

“Ya wanna go to a toros de pueblo in Nono?” Kyle asked. “We could get there right quick.”

I didn’t know what or where he was talking about, but I responded without hesitation, “Sure.” During that phase of my life, I was agreeable to a fault.

Kyle William Allan was from West Texas. When he spoke Spanish, he sounded like the actor Sam Elliot pitching Ram trucks for Univision. He was fond of the expression, “right quick,” which became his Ecuadorian nickname, well, right quick.

He told me that Nono was a small town just Northwest of Quito, the country’s capital. It was holding its annual Toros de Pueblo, the Latin American version of the running of the bulls, the spectacle popularized in Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises.*

Kyle and I were only in our second month of Peace Corps training, but we were already going stir crazy. We were in dire need of a diversion. Besides, it was Sunday and we had the day off. What we didn’t have, I reminded Kyle, was money or transportation. He assured me, “No hay problema. I got it all figured out. First,” he said, “We gotta get us some kers.”

“What’s a kers?” I asked, thinking it might be a secret stash of sucres, Ecuador’s currency.

“You know, Kers, the beer,” he said.

“You mean Coors?” I clarified. “I’m pretty sure we’re not gonna find any here.” We were stationed in the remote Andean village of Lloa, which clung precariously to the face of an active volcano, Wawa Pichincha. There were only two general stores in town and they both sold the exact same provisions. Fortunately for us, one of those “essentials” was Pilsener, the national cerveza of Ecuador. We bartered for a case and enquired about a ride to Nono.

The shopkeeper told us there were no buses, but, because of the festival, we could easily hitch a ride. After only 15 minutes and two Pilseners by the side of the rode, we jumped in the back of an old decrepit pickup truck crammed with enormous propane canisters. Standing in the bed for an hour and a half, I flinched every time we hit a pothole.

As the author’s father says, “When someone is going overboard with compliments, you say, ‘You can tie the bull up outside.’” (photo by: Folwell Dunbar)

Nono was the size of Lloa, but because of the event it had swelled to abnormal proportions. Like an anthill floating in floodwaters, the pueblo was crawling with activity. There were stalls crammed with merchandise and vendors hocking everything from Panama hats to baked crickets. There were children playing football on a dirt field and a band playing Andean folk music in the street. The younger men, including us, did shots of trago, Ecuadorian moonshine to bolster our courage. The main event was a test of machismo.

In the central plaza they had erected a makeshift bullring. It was made from felled Eucalyptus trees bound together with henequen twine. From top to bottom and all the way around, the fence was covered with rubberneckers. Women cradling babies in alpaca blankets, old men wearing tattered fedoras, farmers, merchants and priests all clung to the rails. They were there to see farm league bulls and boys vie for a shot at the majors. The animals that were deemed mean enough would be sent to fight in Quito, and the men who fought them here would be awarded applause, garlands and more trago.

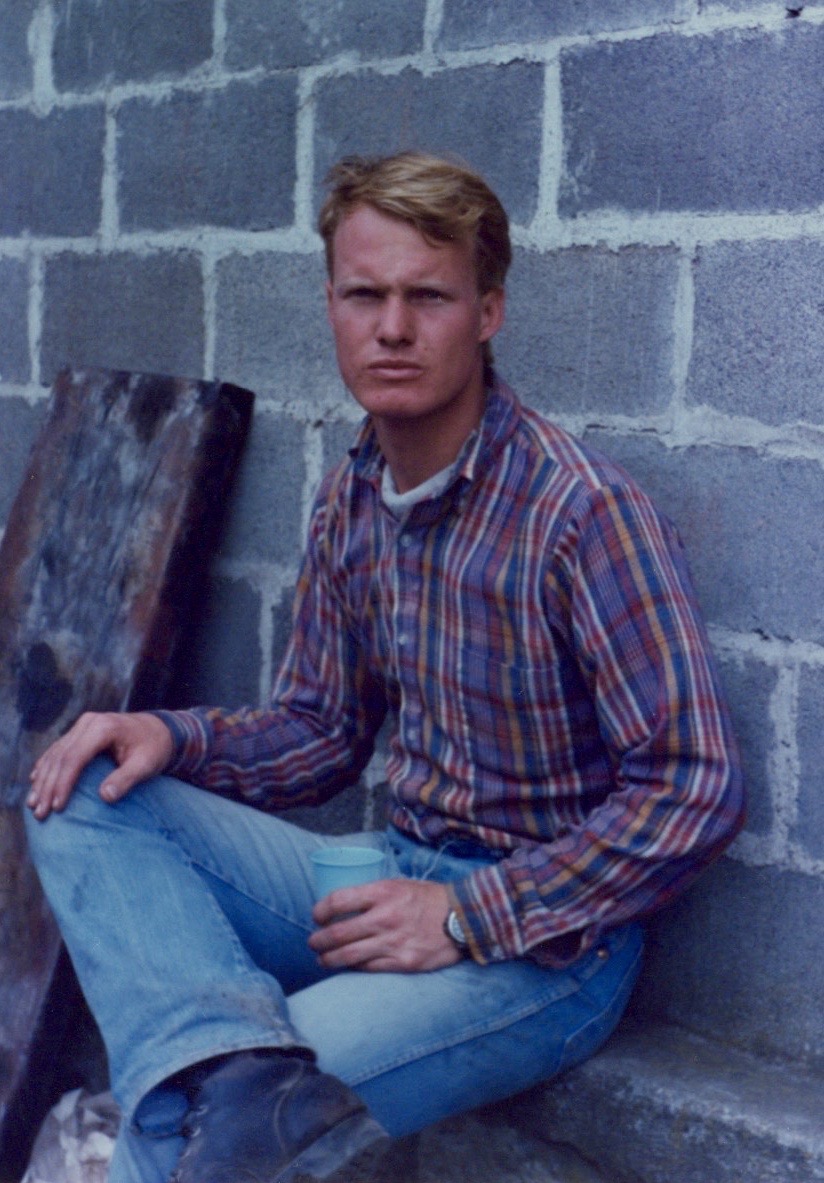

Kyle “Right Quick” Allen in Ecuador (photos by: Folwell Dunbar)

The first few bulls to enter the ring were just happy cows. They could have easily starred in a television ad for Chick-fil-A or the California Milk Advisory Board. The animals just strolled around the ring chewing their cud. Kyle and I, along with dozens of other young men danced around the arena with the placid creatures.

Then, a ruminant obviously cut from a different hide entered the ring. It had shifty eyes and an unpleasant demeanor. It was big and ugly and had no interest in TV ads or chewing cud. The locals immediately sensed danger and streamed from the arena as if someone had yelled, “Fire!”

Not having that sense, or any sense at all, Kyle and I remained in the ring. The bull immediately turned to face its unworthy foreign adversaries. Smoldering snot shot from its nostrils as it pounded the turf with its polished black hoofs. The crowd started chanting, “Grin-gos! Grin-gos!” I wasn’t sure if they were cheering for us or the bull.

Kyle and the author, friends no matter what (photo by: Folwell Dunbar)

Being a pragmatist, I carefully weighed my options. I could run for the fence and try not to get trampled or gored in the back; I could throw myself in front of the animal, save Kyle and be memorialized as muy macho; or, like those insane acrobats from Minoan Crete, I could catapult over the Minotaur and become a Nono legend. As the raging bull approached though, reason quickly surrendered to instinct. It was fight or flight, or, in my case (No, I’m not proud!) hide. I pivoted on the balls of my feet, forklifted Kyle behind his armpits and, drawing strength from enough adrenalin to legally win the Tour de France, I thrust him like a shield at the oncoming beast. Kyle screamed and the audience howled. The bull, as surprised as anyone, unexpectedly stopped in its tracks only inches from my “friend’s” flailing body.

The author in Ecuador with a less dangerous ruminant (photos by: Folwell Dunbar)

The bull looked at Kyle; Kyle looked at the bull; and I looked at the back of Kyle’s head. With no other reasonable option, Right Quick grabbed the proverbial bull by the horns. The bull shook its head in disbelief. Like a damselfly under a windshield wiper, Kyle sailed back and forth. When he finally let go, the bull took a few steps back, lowered its head and prepared for its final, and most likely fatal charge.

At that exact moment a man far more macho (and/or borracho or drunk) than us ran into the ring and smacked the bull on its leathery ass. Fortunately for us, the feeble minded bovine was easily distracted. He spun around to face his latest adversary, allowing us to beat a hasty retreat beneath the fence. The crowed booed and then turned its attention to the new matador.

As Kyle yelled at me, the drunk man hurled insults and expletives at the bull. “Que cameron!” he slurred. “What a shrimp you are!” Que niño!! Que @#$%&!”

Using his poncho as a cape, he jeered and taunted the angry animal. “Toro”! Yelled the crowd as the bull charged pass the man.

As the raging bull turned and charged again, the man stumbled and fell. Trago was getting the better of him. “¡Corre!” yelled the crowd. “Run!”

The man tried to get up, but it was too late. The bull was already on top of him. It reared its head and stabbed at the man. The crowed screamed.

Two men dressed as clowns and carrying large, brightly colored barrels ran into the ring to distract the animal. When the bull turned to confront them, Kyle and I reached under the fence, grabbed the man by his boots, and dragged his body from the ring, leaving a long trail of blood in the dirt. A deep gouge ran from the man’s right kneecap all the way up to his chest. Paramedics put him on a gurney and rushed him off to a waiting ambulance.

The bull was corralled and carted off to Quito. He had earned the right to fight another day on a much bigger stage.

Meanwhile, Kyle and I stood silently on the side of the road trying to thumb a ride back to Lloa. We were done with diversions; we were ready for more training.

To this day, whenever I speak to Kyle, he always starts off right quick, “No, I still haven’t forgiven you for Nono!”

“I know,” I say. “I know.”

Folwell Dunbar is an educator and artist in New Orleans. Kyle is a lawyer in Dallas who is still contemplating suing Mr. Dunbar.

* Here in the Crescent City, we have our own, far safer, version of the running of the bulls. San Fermín in Nueva Orleans features women on rollerblades wearing Viking bullhorns and wielding plastic bats as they chase enamored men up and down the streets. “Tora!”

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

🙂