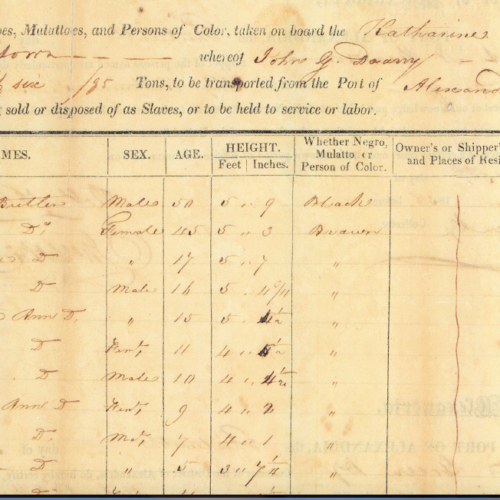

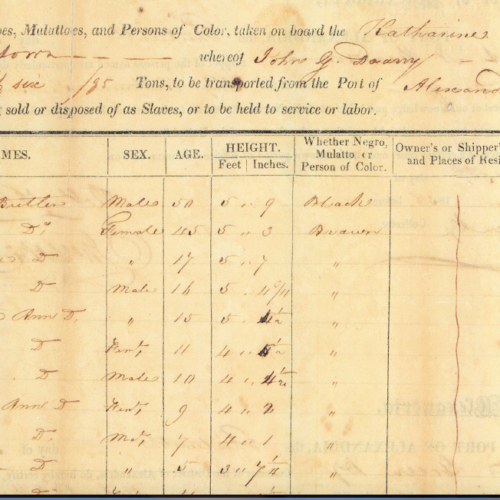

Katherine Jackson Manifest (Photo: Georgetown Slavery Archive).

Shameful actions occurred in Maryland almost 200 years ago, but the pain is palpable for descendants of slaves sold in 1838 to the owners of three sugar cane plantations in Southeast Louisiana. Founded in 1789, Georgetown College – now Georgetown University – was in debt and its president, the Rev. Thomas Mulledy, S.J., decided the solution was to sell off 272 enslaved men, women, and children – 40 family groups – for about $3.3 million in today’s dollars. The abolition movement was gaining ground and they feared their human property might decrease in value. In the 17th, 18th and early 19th centuries, the Society of Jesus was one of Maryland’s largest slave owners with six plantations. The estates had been given to them by the Lords Baltimore; wealthy Catholic families deeded slaves to support their ministry.

“[Georgetown] was built in the blood and the brawn and on the backs of my family,” said Mélisande Colomb. Colomb’s ancestors came to the colony from British Bardados in 1677 as indentured servants, but the women’s papers were destroyed. At that time in the colonies, all black people were necessarily slaves.

“They had their freedom stolen and were put into slavery in perpetuity,” Colomb told a rapt audience at the recent National Humanities Conference held at the New Orleans Marriott. “[The Jesuits] were very concerned about our eternal souls, but had no problem selling our physical souls.” Starting in the 1790s, Colomb’s family sued the Jesuits more than 10 times, trying to regain members’ freedom. The case “Mima Queen & Louisa Queen v. John Hepburn” was brought before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1810, but denied because its proof was verbal testimony, thereby “heresay.” Francis Scott Key, who wrote the lyrics for “The Star-Spangled Banner,” was the Queen family’s attorney.

A retired cook, Colomb received a phone call in August 2016 from Judy Riffel, a genealogist hired by the Georgetown Memory Project, confirming the stories her grandmother told her. Colomb’s great-grandparents and their seven children had been “sold down the river” to work in the fields of sugar cane plantations owned by Dr. Jesse Batey and Henry Johnson, fifth governor of Louisiana.

The slaves were sent to plantations in different parishes, but the majority went to West Oak Plantation south of Maringouin (translated as “mosquito”) in Iberville Parish. “My family was in the harshest part of Louisiana,” said Jessica Tilson, another descendant presenting at the humanities conference. Even so, few have left. “We’ve been living on the same property since 1838. They had already been separated so didn’t want to be separated again.”

For Georgetown University, the convenient story had been that all the slaves had perished, which was true, but they left many descendants, now 7,000 identified individuals, but probably more than double that number.

“My grandmother knew her grandmother who was sold,” Colomb said. “Lo and behold in the last two years, I have gone to Maryland and opened the books and seen with my very own eyes that what my grandmother knew was true.”

The Jesuits’ slave history was known to scholars, but most university staff and students were unaware; although, it was well documented, according to Adam Rothman, a Georgetown history professor whose study focuses on American slavery. The Articles of Agreement drafted by the Rev. Thomas Mulledy, J.S. identified 200 children by name. A Working Group on Slavery, Memory and Reconciliation, comprised of students, alums and faculty, was formed in 2015 to identify and support descendants, as well as to educate the university community. Richard Cellini, chief executive of a technology company and a Georgetown graduate, hired eight genealogists to locate the descendants, using public records, including bills of sale, Census and court records. The Georgetown Memory Project has become the largest genealogical study ever conducted in the United States.

“Everybody knows about the Mayflower people, but this was more people,” Colomb said.

Not all the Jesuit slaves were sold and so many connections exist between the descendants of slaves from the Maryland and Louisiana plantations. Descendants formed the GU272 Descendants Association and made recommendations to the university.

“Nothing about us without us,” descendants told Georgetown’s president.

In attempts at reconciliation, Georgetown has renamed two buildings for former slaves, Isaac Hawkins and Anne Marie Becraft, replacing names of the Jesuits who were responsible for the sale. The university has also granted legacy status to descendants.

Colomb began university studies at Xavier University many years ago, but never graduated. She decided in 2016 to enroll as a Georgetown freshman. ” I felt that there should be adult representation on this campus so no student who graduates in four years remains ignorant.”

“The USA as a whole was a slave society. It was created and has been maintained willfully keeping people ignorant,” Colomb said, “but we need to stand up to truthful scrutiny and examination.”

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.