Editor’s Note: Lacar Musgrove is a writer who dives into the history of bikes, cycling, and all things New Orleans. You can read her full “Astride Lofty Wheels” series and more of her work and research on her cycling history blog.

The obituary of Ritchie Betts. (Photo: NYT archives)

In the last two decades of the 19th century, the bicycle rose from a technological curiosity to a consumer item so popular with the mainstream middle class that it altered not only the culture but the physical space of cities and their suburbs. Credit for this phenomenon lies with the stringent efforts of the bicycle clubs that formed all over the United States, including two in New Orleans whose members actively courted the press to gain both social popularity and political power for cycling in New Orleans and beyond.

In 1887, an 18-year-old railroad clerk named R.G. “Ritchie” Betts founded the Louisiana Cycling Club in New Orleans. The LCC was the second major cycling club formed in the Crescent City, after the New Orleans Bicycle Club, which was formed in 1881 by a jeweler named A. M. Hill. Under the aegis of Betts, the youthful LCC quickly outshone the NOBC as a vibrant and beloved organization that succeeded in bringing cycling into popular favor a city that was characteristically resistant to the new technology. With Betts’ leadership, the first cycling track races in New Orleans were held at the Audubon Park Driving Track beginning in 1887, and the annual cycling races at Audubon immediately became one of the most popular spectator events in New Orleans.

Betts competed in those annual racing events and the club’s road races held throughout the year. He made his name, though, not as an athlete but as a journalist, organizer, and cycling advocate. When bicycles first arrived in the city around 1880, these strange new contraptions were immediately unpopular with the public. Lafcadio Hearn hated them, calling them “wild, treacherous, diabolical, and unspeakable. . .. Happily the Bicycle,” he wrote in 1881, “is so vicious that few, even among the wickedest of New Orleans boys, dare to ride it.” Enraged citizens attacked riders and demanded the vehicles be banned entirely.

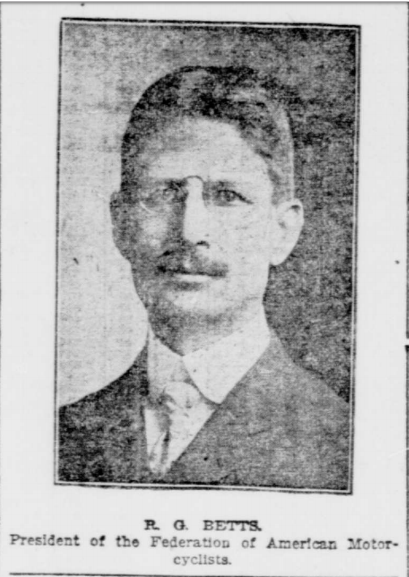

Betts from NY Tribute Article from November 2, 1903

Using the sway of his social connections, Betts got articles printed in the Daily Picayune in which he mused on the pleasure and usefulness of the bicycle while courting its public acceptance on city streets. To win the hearts of New Orleanians, he led the effort to put on the dazzling public spectacle of the Carnival Lantern Parade of 1887. He also penned lively articles about cycling in New Orleans and the escapades and amusements of the LCC for various cycling magazines, including Bicycle South and The New York Wheel, in his youth signing his missives with the whimsical nom de plume “Bettsy B.”

Through their buoyant promotional efforts, Betts and the LCC convinced the public of the bicycle’s worth as salubrious recreation and private transportation, achieved the legal rights of cyclists to public roads, and even inspired the city to improve the streets. Likely owing to its proximity to the festive Creole culture of New Orleans, the LCC distinguished itself from the stiff old-fashioned Victorian ethos of other cycling clubs in the United States. With its influence, a modern youth subculture around the bicycle soon flourished in New Orleans, ushering in the Bicycle Boom of the 1890s.

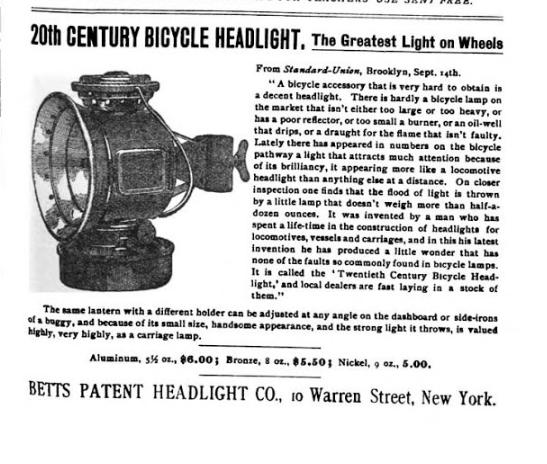

In 1891, Betts moved to New York and became the assistant editor of The New York Wheel. With the invention of the motorcycle, Betts quickly took up the new machine and became the first president of the Federation of American Motorcyclists (precursor to the current American Motorcyclist Association), advocating for the legal rights of motorcyclists to public roads. In general, he was a man who kept busy. In 1894, he went on a bicycle tour of Europe. In 1895, he founded the Betts Patent Headlamp CO, later named the 20th Century Manufacturing Company, fought in the Spanish-American War in 1898, and ran unsuccessfully for Mayor of White Plains, New York, in 1925.

In 1903, he helped organize the first “rumble” of the FAM at Manhattan Beach in Brooklyn, which included track races. Having by that time become editor of Bicycling World, he soon changed the name of that magazine to Bicycling World and Motorcycle Review. Such was the reach and power of his influence that the newspaper San Francisco Call referred to him in 1908 as “The Father of American Motorcycling.” Betts wrote at the time that “Los Angeles [motorcycle] clubs are the finest of any in the world. For these reasons that it may be considered at present California is the home of the motorcyclists.” Even after he’d moved on to motorcycling and then motorcars, Betts continued to pen articles for the New York Times in favor of bicycles on the streets of New York well into the twentieth century, when bicycles had been relegated to the poor man’s transportation.

1895 advertisement for the carbide bicycle headlamp that Betts invented.

At the time of his death in White Plains, New York, in 1951, Betts had risen as a prominent civic leader, heading several social and political organizations. His name has now faded from popular memory, but Ritchie Betts, the sharp-witted writer and talented social organizer from New Orleans, surely had a hand in carving out a little corner of American culture.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

[…] Find it here. […]