Editor’s Note: The following series “Big Easy and the Environment” is a week-long series curated by Lindsay Hardy as part of the Digital Research Internship Program in partnership with ViaNolaVie. The DRI Program is a Newcomb Institute technology initiative for undergraduate students combining technology skillsets, feminist leadership, and the digital humanities.

March is the beginning of spring in New Orleans, the trees are changing, the pollen is falling, and the humidity is just starting to creep in. As the seasons quickly change each year, and New Orleans becomes warmer, it makes people start to question: how quickly is New Orleans climate and environment changing? This grouping of articles explores and appreciates New Orleans’ changing environment as it relates to film in the past, present, and future. “Tina Freemans: Lamentations’ for Environments Lost?” was originally published on NolaVie by Mary Rickard on September 10th, 2019. “Tina Freemans: Lamentations” was a photography art showing of different contrasting environments and their changes. The article includes quotes from the artist, descriptions of her process, as well as pictures from her show. It provides a visualization of the climate and the way that New Orleans engages with these visualizations and reacts to them.

Opening Wednesday, September 11 at New Orleans Museum of Art, Tina Freeman: Lamentations, an extraordinary exhibition of startling, environmental photography by the acclaimed visual naturalist, will challenge viewers to reflect on the interconnectedness of the biosphere. Most Louisianans already understand wetlands are disappearing, but do they fully accept that receding glaciers 8,000 miles away are eroding coastlines here? NOMA’s photographic exhibition makes neither scientific nor political argument but offers a rare opportunity to experience extremely different environs in the process of transition.

“You can walk right into those landscapes,” says Russell Lord, curator of photographs, and draw your own conclusions.

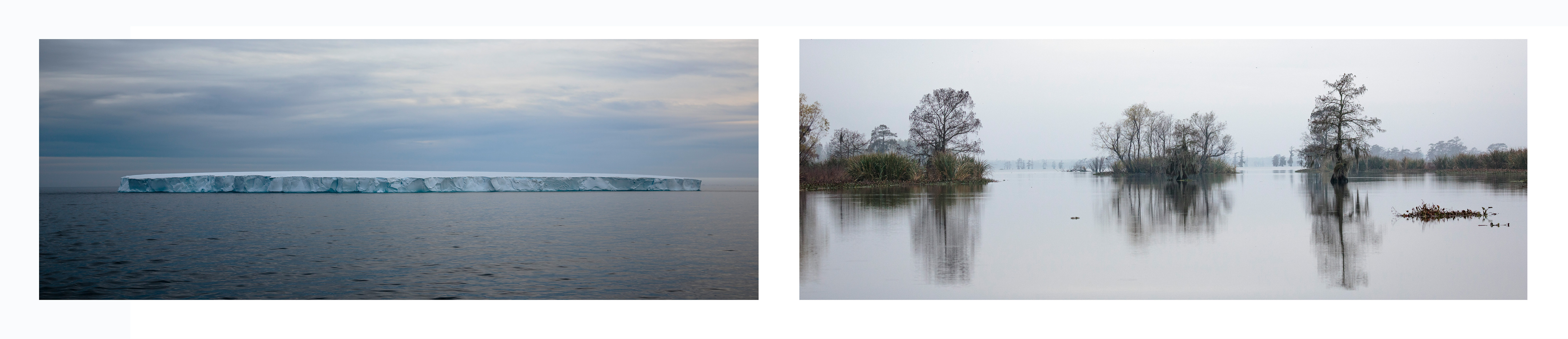

Stark, glacial icebergs are positioned beside lush, verdant swamps. (Photos by: Tina Freeman)

“First, I want people to see how beautiful the wetlands are, the ice is, and to be seduced by it,” says Freeman, who is, foremost, a photographer. Her thesis has emerged over the past eight years, from her first Nordic voyage and, later, in the marshlands she explored as a girl, fishing with her father and brothers. Over several journeys, she began to connect the dots that spell out global transformation.

“I love to photograph ice and wetlands. They are not like Yosemite or another iconic image. You can’t go and rephotograph the exact same iceberg because it is constantly changing – I love that,” Freeman says.

Twenty-seven pair, out of thousands, of photographs shot on seven trips to Antarctica, Greenland, Iceland, Finland and the North Pole are matched with those taken in the wetlands of Louisiana to tell heartbreakingly beautiful stories about climate change, ecological balance and the interconnectedness of natural landscapes.

When Lord began discussing this exhibition with Freeman a few years back, her earliest pictures had not been shot with the intention of pairing. She made further excursions around marshlands near Morgan City, South Pass, Avoca Island and the Caernarvon diversion to develop her theme. Now, contrasting scenes, showing similar shapes and artistic compositions, are arranged as diptychs, inkjet-printed on the same sheets. Struck by the sheer beauty of nature, viewers may consider why particular images, including cemetery tombs, rusting oil industry equipment, cypress knees and animal skeletons, were placed side-by-side. Freeman answers her own question: “It’s because they are connected. What happens to the ice ends up in our backyard.”

With the exception of the artist’s statement, photographs appear without labels, only identifying locations, leaving viewers free to interpret their meaning. “[The photographs] run the risk of just being seen as beautiful images,” Lord said. “In some ways, they are documentary, in others, they are artful.”

Lord’s divergent personal reactions to the photos are “approachable and terrifying.”

(Photos by: Tina Freeman)

In each pair of images, one from the Arctic or Antarctic and its companion from the Louisiana wetlands, the meaning of each individual image is framed and provoked by the other. A fallen tree echoes the contours of a musk ox skeleton, for example, with both becoming specters of loss. Each work becomes a declarative sentence, almost shouting that we cannot possibly understand this without that. When we begin to understand that this is the life-threatening loss of coastal refuge, and that is the increasingly fast erosion of glacial ice,the global stakes truly come into focus. – Russell Lord, Curator of Photographs, New Orleans Museum of Art

Another nature photographer who has spent years doing time-lapse photography of icebergs, James Balog, said in a TED Talk: “Most of the time, art and science stare at each other across a gulf of mutual incomprehension…Art, of course, looks at the world through the psychic, the emotions, the unconscious and, of course, the aesthetic.” In Balog’s analysis, photography clarifies the mis-perceptions about climate change by making “the invisible visible.”

Climate change is often explained with charts and graphs, illustrating rising temperatures, elevated sea levels, areas of drought and more frequent and intense storms. Freeman, however, examines the phenomenon aesthetically. Her vistas are visually arresting in their own right, but the undercurrent is a predicted 2 percent increase in global temperatures.

The science of global warming is represented in an all-encompassing list of glaciers on the last wall. Of 2,600 glaciers, the vast majority are retreating.

(Photos by: Tina Freeman)

The New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA) presents the exhibition Tina Freeman: Lamentations, on view September 12, 2019 through March 8, 2020.

The exhibition is accompanied by a publication of the same name, (Lamentations) published by the New Orleans Museum of Art and the University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press. Featuring essays by Tina Freeman and Russell Lord, the book also includes contributions on the Louisiana wetlands by David Muth, Director, Gulf Restoration Program at the National Wildlife Federation, and on glacial activity by Brent Goehring, Assistant Professor, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Tulane University. It also features graphic information about glacial growth and disappearance, and the changing shape of the state of Louisiana as a result of sea-level rise.

(Photos by: Tina Freeman)

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.